There’s a story about how Bruce Kania came to his concerns about water quality.

One day in 1999, he watched as his black dog jumped into a pond and came out streaked with rusty orange. It had encountered an algal bloom of cyanobacteria. Such blooms can be toxic. This one wasn’t, so the dog, after being cleaned up, was none the worse for its experience.

But that experience eventually led to Kania’s invention of a form of floating wetland for cleaning up polluted water, and to launch a company called Floating Island International.

The firm is based in Shepherd, Mont., on about 140 hectares of land along the Yellowstone River. Several ponds dot the property, a couple of which he had had dug out and filled so that they became living laboratories.

One of them, Fish Fry Lake, figures in a lot of the things he writes, usually pertaining to the idea of biomimicry, an interest that drives his research and product development.

Kania is a long-time outdoorsman, an avid fisherman who grew up fishing the waters of Northern Wisconsin. Some of the best fishing was round islands of peat floating on clean, clear water. His purpose in digging ponds on his Montana property was to see if he could re-create those floating islands.

His Fish Fry Lake is a small pond, with a surface area of just 2.5 hectares, or 6.5 acres. But after it had been filled with water, he said in a recent interview, "I ended up with 6.5 acres of solid algae."

"There were patches of cyanobacteria with orange colours, and blue colours, and stuff that made you really concerned about your dog perhaps taking a sip.

"Now I’ve got water clarity that can extend as far as 19 feet.

What cleaned up the water was, of course, the floating islands Kania had invented, islands similar in function to the peat he had seen years before in Wisconsin.

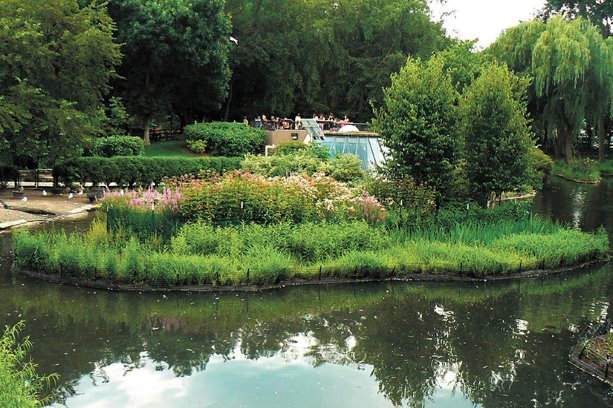

The islands, which he christened BioHavens, are made up of recycled plastic drink bottles, shredded and injected with a polymer foam to create a buoyant matrix in which native grasses and aquatic plants are planted. Eventually, the plant roots permeate the matrix and extend below the island, providing shelter for fish and all manner of other aquatic creatures.

As the root systems grow, they become coated with biofilm, which is simply microorganisms in which the cells stick to each other, eventually coating the roots and other surfaces, like rocks, with slime. That slime absorbs nutrients like phosphorus from the water. It also captures and holds particulate material, clarifying the water in the process.

That’s precisely what the peat islands of Kania’s youth do. His floating islands had duplicated Nature’s process for clarifying and purifying water.

It’s called biomimetics, copying nature in order to solve a problem, and the idea has been around for a long time.

The ancients studied birds in flight, looking for a way for humans to fly. Leonardo da Vinci, who lived 500 years ago, studied the anatomy and flight of birds, and made notes and sketches, although he never succeeded in inventing a machine that would fly.

The Wright brothers, who flew the first heavier-than-air machine in 1903, had studied pigeons in flight.

The word "biomimetics" was coined by biophysicist Otto Schmitt in the 1950, but did not come into the main stream until, in 1997, scientist and author Janine Benyus titled her first book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. Since then there has been a steady stream of products brought to market that mimic nature in some way.

There are now materials for coating glass so it sheds rain in the same way a lotus leaf does, and paints that shed rain the same way. There are climbing robots that can move along vertical walls without falling, much the way geckos can.

And there are floating wetlands that mimic nature’s peat bogs.

Some within the water industry were reluctant to accept Kania’s invention. But with Fish Fry Lake as a laboratory, he was able to provide the research that would convince people of their merit.

By 2005 Floating Island International was in business, and within two years 1,600 of Kania’s islands had been launched in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Korea, the United Kingdom and Europe.

By 2010 more than 4,000 islands had been launched worldwide, and more than 30 different possible applications had been found for them.

Now the number of island launches is around 6,000, and the technology has established a track record of 12 years of freeze-thaw cycles in Montana, resiliency in the face of Hurricane Isaac in Louisiana, stormwater management in New Zealand, and in Canada, where a company called VITA Water Technologies, of Lethbridge, Alta., last season launched 30 BioHaven projects. Clients included the cities of Lethbridge and Calgary, the provincial departments of agriculture and the environment, and Strathcona County. Research collaborators include the University of Alberta, U of Calgary, and Olds College and Lakeland College.

The islands were installed in stormwater ponds, farm dugouts and behind a dam.

The application of biomimetic principles still drives Kania’s research efforts.

He said that fresh-water sponges had been identified in his little Fish Fry Lake. They’re filter feeders, like their saltwater cousins, and they help clarify the water.

He hadn’t even known that there was any such thing as a fresh-water sponge, he said, "until a visiting biologist from New Zealand identified them for me."

They contribute to the biocomplexity of a floating island, whether it’s of peat or a man-made equivalent.

"As you take care of your water, you end up with every niche, every life opportunity, being filled with something," Kania said.

"You end up with a biocomplexity of plant material, invertebrates, fish, dragon flies, damsel flies, you name it.

"Nature wants to help us out."

1/2

Photo:

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed