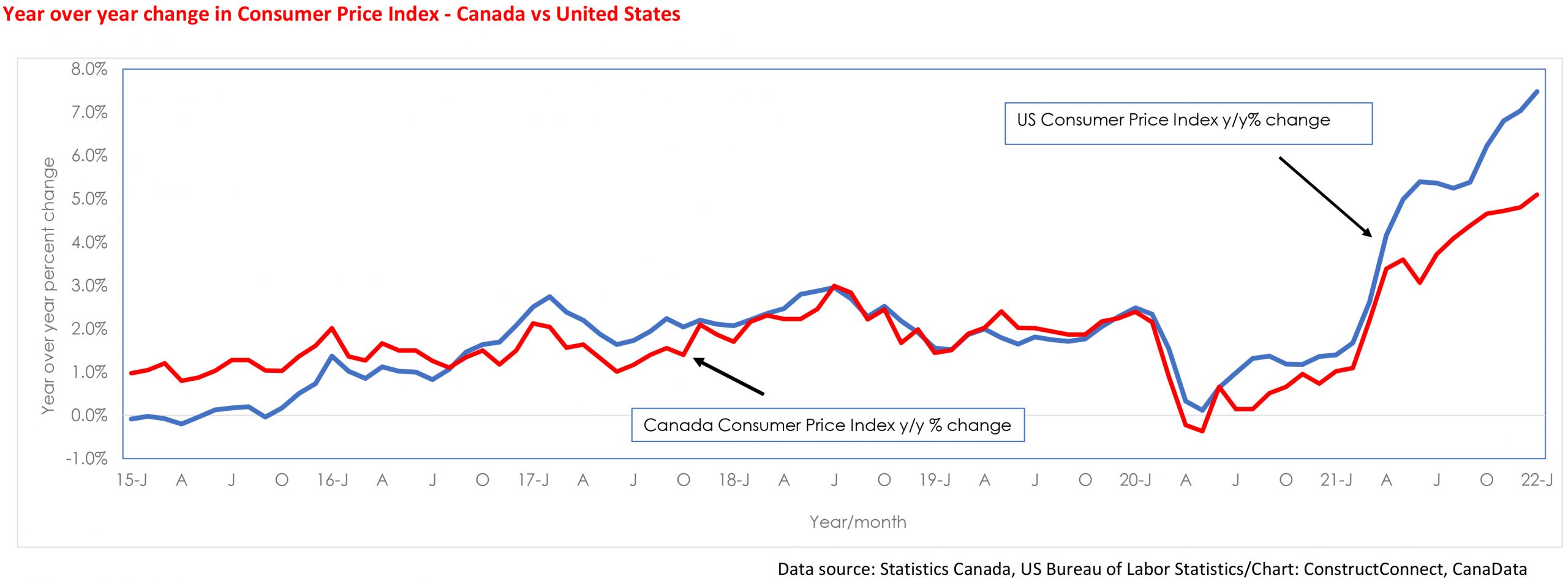

Canada and the United States are in inflationary bubbles. This assertion is confirmed by a multitude of statistical indicators in both countries.

In the U.S., headline inflation hit a 40-year high of +7.5% y/y in January. While much of this gain was ‘fuelled’ by a +27% y/y increase in energy prices, core inflation, excluding food and energy, was up by +6% y/y, also a 40-year high.

The annual change in the U.S. producer price index (PPI), which reflects prices at the wholesale level, has accelerated from a COVID-19-depressed low of -5.3% y/y in April of 2020 to a 40-year high of +13.3% y/y this past November.

The rapid escalation in consumer and producer prices has been accompanied by an unprecedented +18% y/y run-up in U.S. median house prices. The jump in prices has not cooled home sales. They hit a 9-month high of 811,000 units in January.

The combination of strong demand for motor vehicles and depressed new car inventories, due to a shortage of computer chips, has contributed to a sharp rise in the price of used cars. Since January of 2021, they are up +40%, four times the +10% y/y gain they posted a year earlier.

Not surprisingly, the recent runup in prices has given rise to an increase in inflationary expectations. Over the past year, the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumer Sentiment has seen its ‘Expected Change in Inflation Rates’ measure increase from +3.0% to a 40-year high of +4.9%.

As the chart illustrates, the headline inflation rate in Canada has not yet caught up to the U.S. figure. That said, at +5.1% y/y in January, it’s higher than at any time since September 1991. As in the U.S., higher energy prices (+23% y/y in January) accounted for much of the gain, followed by shelter costs (+6.2% y/y) and motor vehicle prices (+5.2% y/y). Unlike the U.S., Statistics Canada does not publish data on used car prices. However, a dearth of new cars for sale (due to the ‘chip’ shortage) has encouraged more car buyers to choose ‘used’. According to J.D. Power, publisher of the Canadian Black Book on motor vehicles, average used car prices in Canada have increased by +47% over the past 12 months.

The same fundamentals which have underpinned demand for autos (i.e., record- low interest rates and sustained employment growth) have caused the inventory of unsold homes to drop to record lows and driven existing home prices up by an unprecedented +28% over the past year.

Furthermore, the fact nearly 80% of the CPI’s subcomponents are rising more than +2% y/y suggests that inflationary pressure is broadening. In its latest (Q4/2021) Business Outlook Survey, the Bank of Canada reported that an unprecedented 67% of respondents expected headline inflation to average above +3% over the next two years.

Inflation fuelled by government spending and expansionary monetary policy

Analysts have attributed the recent surge in the CPI and the accompanying rise in asset prices to several factors. Among them are supply chain issues, shortages of computer chips, and excess pent-up demand. Also making major contributions, however, have been unprecedented increases in government spending in both Canada and the U.S. since late 2019 and the decision by central bankers to use Quantitative Easing (QE) to inject billions of dollars into the financial system to drive interest rates as close to zero as possible.

In the past, historically low-interest rates have encouraged firms, households, and governments to take on more risk than they otherwise would have ventured. In Canada and the U.S., monetary authorities have recently made hawkish comments signaling their intentions to raise interest rates in the very near term. The Bank of Canada’s next policy rate announcement will be on March 2 and the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee meeting is scheduled for March 15-16.

By how much and for how long will the U.S. Fed and the Bank of Canada raise interest rates? While both central banks have indicated they are going to raise rates, their extended ‘wait and see’ approaches suggest tightening will be reactive rather than proactive. Augmented by big jumps in government deficit spending, there will continue to be too much money chasing too few goods.

Failure by the central banks to deflate inflationary bubbles will increase the risk that prices will pop as they did in 1975, 1980 and to a lesser extent in 1990. By not doling out their interest rate medicine sooner, central banks may be forced to adopt more aggressive and more painful treatments later.

Graph 1

Recent Comments