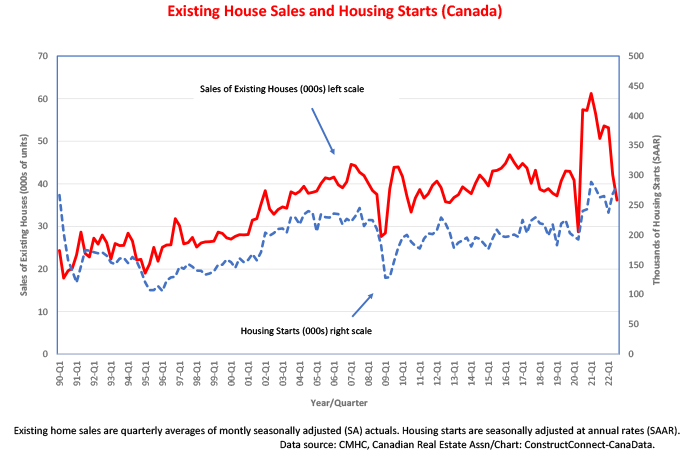

The close linkage between sales of existing homes and housing starts which has generally persisted over many years (see chart) appears to have weakened since early 2021. A tailing-off of the post-pandemic surge in sales combined with a cooling of demand caused by the steady rise in mortgage rates has caused existing home sales to fall by -40% from their peak in early 2021. Housing starts are down by just -0.5% over the same period.

CMAs which have seen significant declines in starts include London, Ontario (-44%); Peterborough, Ontario (-43%); Greater Sudbury, Ontario (-42%); Guelph, Ontario (-38%); Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario (-34%); and Sherbrooke, Quebec (-32%). However, starts have risen in 18 of the country’s 34 CMAs, led by Brantford, Ontario (+90%); Abbotsford-Mission, BC (+52%); Barrie, Ontario (+29%); St. John’s Newfoundland (+27%); Moncton, New Brunswick (+26%); and Trois Rivieres, Quebec (+22%).

Four key indicators suggest the disconnect between home sales and housing starts is unlikely to persist and that the retreat in home sales will soon drag housing starts lower. First on the list is the lagged impact of the 350 basis-point increase in the Bank of Canada’s target for the overnight rate. Furthermore, an October 26th announcement by the BoC asserted that its “policy rate will need to rise further”. According to a recent Royal Bank of Canada report, “buying a home has never been so unaffordable” due to the very large share of income the average household needs to cover the costs of homeownership (i.e., 90% in Vancouver and 83% in Toronto).

Second, the Conference Board of Canada’s index of consumer confidence dipped further to 70.3 in October due to the combination of higher interest rates and the eroding impact of rising inflation on purchasing power. Fewer than 10% of those surveyed consider that now is a good time to make a major purchase.

Third, after hitting a high of $8.3 billion in June, the value of residential building permits dropped by -15.6% in September due mainly to a -19% month-over-month decline in applications to build multiple dwellings. The census metro areas (CMAs) which have experienced the most significant year-to-date declines in number of applications include London, Ontario (-40%); Hamilton, Ontario (-33.4%); Sherbrooke, Quebec (-33%); Lethbridge, Alberta (-33%); and Toronto, Ontario (-27%).

Fourth, in line with the steady rise in the number-of-months’ supply of homes for sale since December of 2021, the inventory of completed and unoccupied new dwellings has moved gradually higher since mid-year. CMAs that have exhibited above-average increases in the number of completed and unoccupied dwellings over the past five months include London, Ontario; Kelowna, BC; and Kingston, Ontario.

There are two key questions triggered by this forecast of a slowdown in residential construction. First, how severe will it be? And second, what will be its duration? Since 1955, Canada’s housing market has experienced three noteworthy cyclical downturns. The first began in 1976 and lasted for approximately 7 years, while the second, which started in 1987, ended 8 years later in 1995. On average, housing starts tumbled by 140,000 units in those two major corrections.

The most recent contraction, which was triggered by the 2007 financial crisis, lasted just two years, and saw starts fall by about 80,000 units.

It is impossible to accurately gauge how long it will take monetary authorities on both sides of the Canada/US border to bring inflation back to the 2% target both are aiming for.

There are two factors that could moderate both the length and severity of the downturn. First, Canada’s unemployment rate at 5.2% is just slightly above the record low of 4.9% it reached in June of this year. Reflecting acute labour shortages across the country, 15 of Canada’s major industries have high job vacancy rates, led by accommodation and food services and construction, at 10.4% and 7.4% respectively.

Additionally, following a COVID-induced hiatus in late 2021 and early 2022, Canada has admitted a record 657,000 international migrants and the government recently announced plans to welcome 500,000 a year by 2025. Based on history, most of the new arrivals will move to Ontario, British Columbia, or Quebec.

Despite these mitigating factors, we expect housing starts to fall from an estimated 260,000 units this year to 200,000 units in 2023 before moving up slightly to 224,000 units in 2024.

John Clinkard has over 35 years’ experience as an economist in international, national and regional research and analysis with leading financial institutions and media outlets in Canada.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed