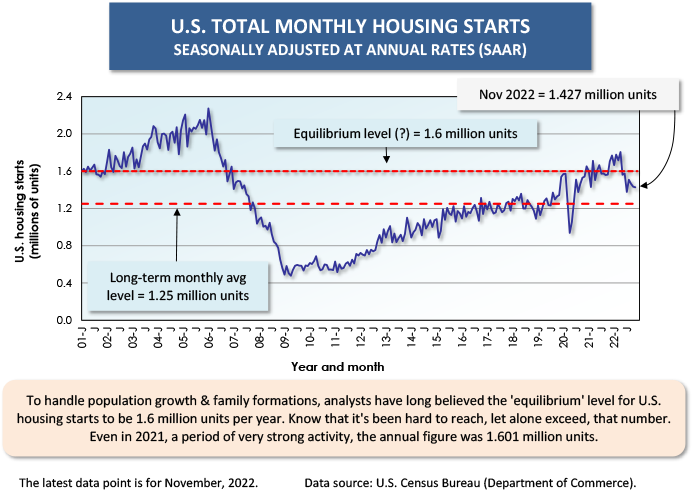

Given the increases in mortgage rates that have transpired, significant slides in homebuilding activity are being taken for granted in the U.S. and Canada. Based on the latest housing starts statistics, this is already underway and clearly apparent in the former more than in the latter. See Graph 8 below, where Canadian housing starts have been moving mostly sideways throughout this year, while U.S. starts have been exhibiting significant declines month to month.

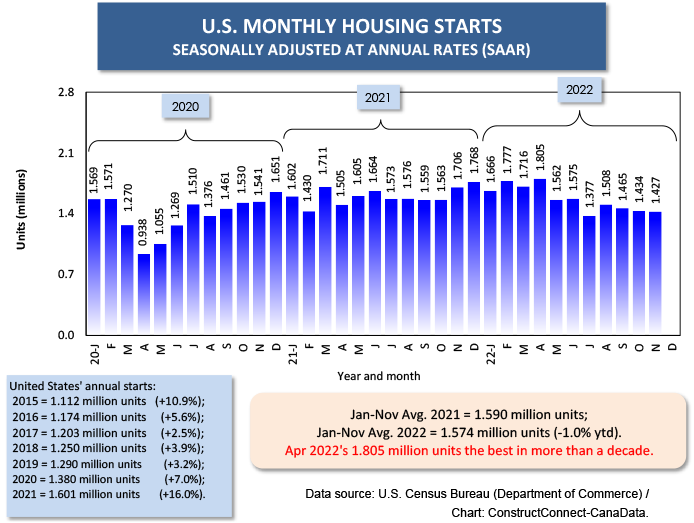

The monthly seasonally adjusted and annualized (SAAR) figure on housing starts in the U.S. has dipped below 1.5 million units in four of the last five months. Prior to this past July, they were above 1.5 million units in 16 straight months, topping out at 1.805 million units in April 2022.

The monthly seasonally adjusted and annualized (SAAR) figure on housing starts in the U.S. has dipped below 1.5 million units in four of the last five months. Prior to this past July, they were above 1.5 million units in 16 straight months, topping out at 1.805 million units in April 2022.

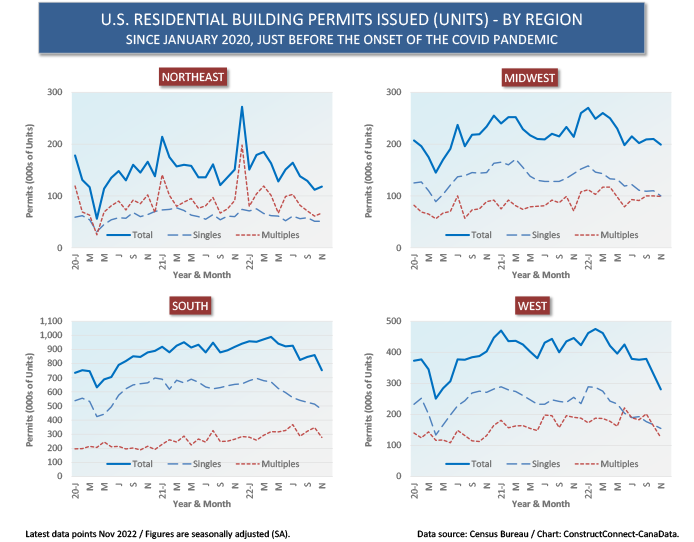

A cause of more concern than the ‘starts’ numbers, however, is how residential building permits have been performing. The permits data series usually provides a couple of months forward glimpse into where starts will be heading. The permits numbers have turned nasty.

Graph 1 highlights the extent of the coming damage. Total U.S. residential building permits have been cratering for most of 2022.

Graph 2 sheds light on where the problem with permits is cropping up most seriously. Total permits are off somewhat in the Northeast; they’re in obvious decline in the Midwest and South; but they’re dropping alarmingly in the West.

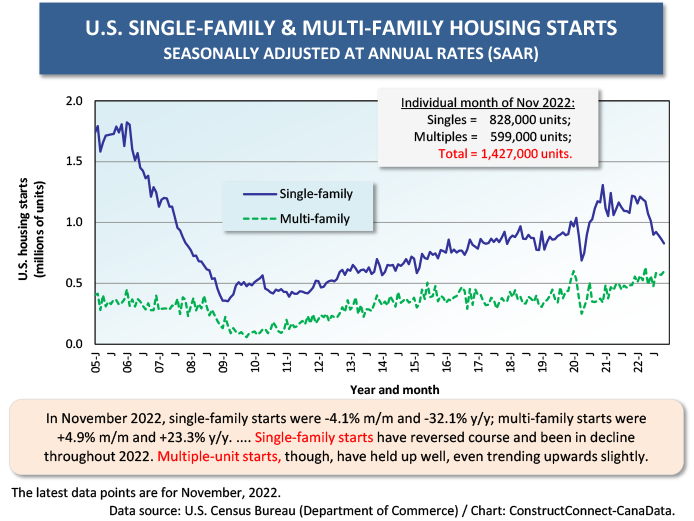

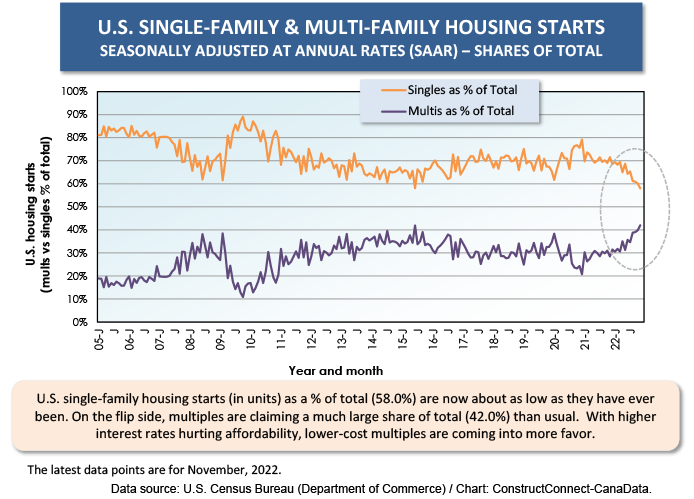

Graph 2 also highlights something else interesting that is occurring. In the Midwest, South and West, single-family permits are in considerable distress, certainly more so than the multi-family variety. In fact, in the Midwest and South, multi-family permits aren’t slowing down at all.

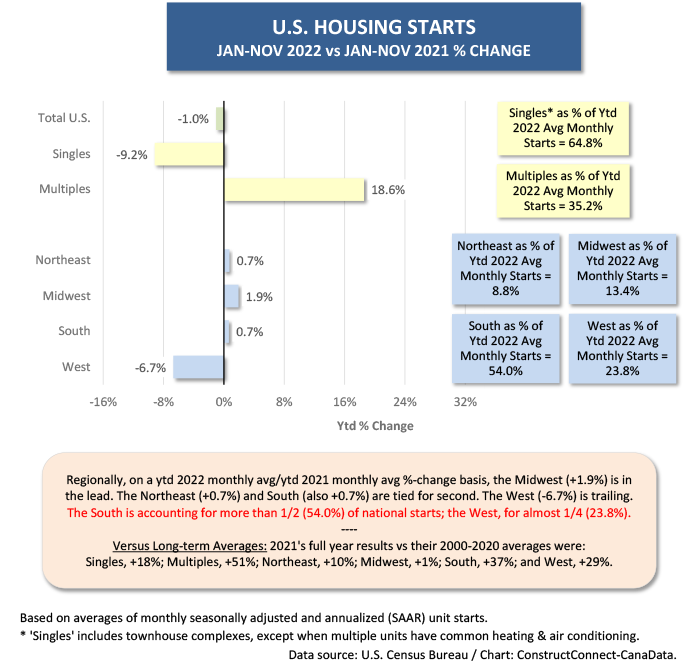

It’s also interesting that while the U.S. as a whole is known for having a larger share of its total starts made up of singles as opposed to multiples, there is currently near equality in units (based on permits data) between the two types of residential structures in the Northeast, Midwest, and West, with only the South being an outlier.

The South, which accounts for more than half of all U.S. housing starts, continues to see considerably more single-family units than multis, but the gap is narrowing.

The weakening residential real estate market has become apparent in pricing. For existing homes, the S&P Corelogic Case-Shiller price indices have now fallen below double-digit percentage-change advances year over year. For a while, they were hovering around +20.0% y/y.

In October, the national Case-Shiller index was +9.2% y/y. The 10-City Composite was +8.0% and the 20-City Composite, +8.6%. Not all cities were observing price restraint, especially in Florida. Resales in Miami were +21.0% y/y and in Tampa, +20.5%.

It would be nice to think that the cooling in residential real estate has led to one good thing, the improvement in consumer confidence that the Conference Board has been finding. Its index perked up to 108.3 in December from 101.4 in October (with a base of 1985=100.0). That turn of events, though, rather than relating to current developments in the housing market, is being ascribed in large measure to the notable pullback in the price of gasoline.

The Cliché of Bursting the Bubble in Canada

For Canada, it has become a cliché for foreign observers to say that the housing market is facing imminent collapse. That the bubble is about to be burst. This kind of talk has been going on for decades and it’s based on the extraordinary heights to which home prices have risen in Canada’s major cities, especially Vancouver and Toronto.

A correction is underway. The price map provided by the Canadian Real Estate Association (CREA) notes a -12.0% y/y decline in existing home sales prices nationally. Greater Vancouver is -0.6% y/y and Greater Toronto, -5.5%.

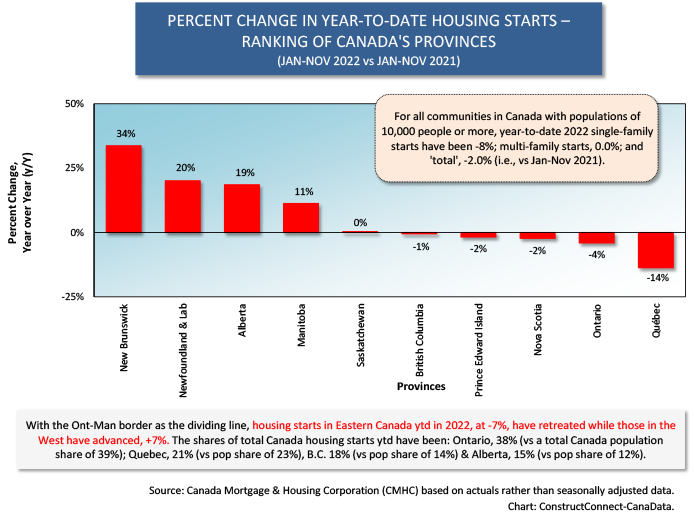

But know that there’s one key factor underlying Canadian housing demand, the nation’s remarkable record of population growth. The Q4 2022 over Q4 2021 change in the nation’s total population was +2.3%. To put this in perspective, the comparable y/y figure in the U.S. has been +0.4%.

Ontario’s latest annual population increase was +2.4%; British Columbia’s, +2.5%; and Alberta’s +3.0%. Quebec’s gain was a relatively modest +1.4%; although, on its own, that was quite respectable.

Warranting special mention is that the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick (+3.1%), Nova Scotia (+3.3%), and Prince Edward Island (+3.8%) have recently been experiencing y/y population gains far outside their norms.

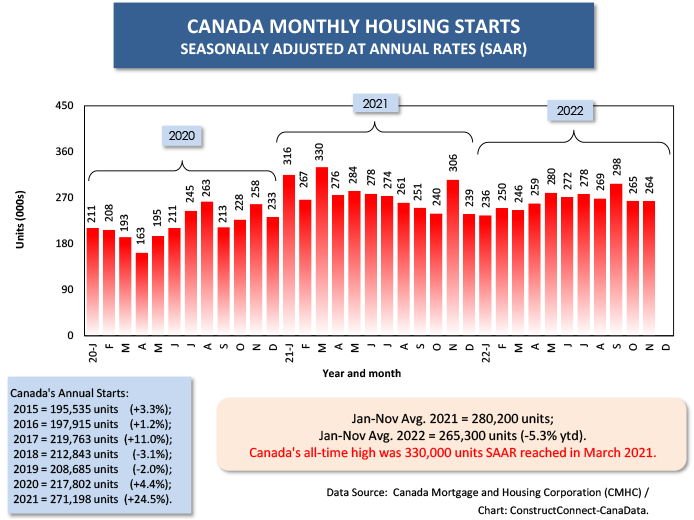

From Graph 9, the January-November average of monthly housing starts in Canada this year compared with the same time frame last year may have been -5.3%, but at a level of 265,000 units, it was way above the long-term (2000 to 2020) figure of 200,000 units.

Plus, there isn’t a government in the country, at the federal, provincial, or municipal level, that isn’t asserting the need for an acceleration in the provision of housing.

Graph 1

Graph 2

Graph 3

Graph 4

Graph 5

Graph 6

Graph 7

Graph 8

Graph 9

Graph 10

Graph 11

Graph 12

Graph 13

Alex Carrick is Chief Economist for ConstructConnect. He has delivered presentations throughout North America on the U.S., Canadian and world construction outlooks. Mr. Carrick has been with the company since 1985. Links to his numerous articles are featured on Twitter @ConstructConnx, which has 50,000 followers.

Recent Comments