Global inflation may be cooling, but it’s not cold

From a global perspective, important price measures are signaling that inflationary pressures have moderated over the past few months. First, in 28 OECD countries, the latest (December 2022) inflation rate has slowed to +9.4% year over year after hitting a high of +10.9% in October. Second, the Baltic Dry Index, calculated by the Baltic Exchange in London UK, after reaching a peak of 5,500 in late 2021, has gradually trended lower in the wake of a steady easing of the supply chain shortages which developed post-Covid-19. Currently, the Baltic Dry Index, which is a measure that reflects global demand for commodities and raw materials, stands at just 538, its lowest value since May 2020.

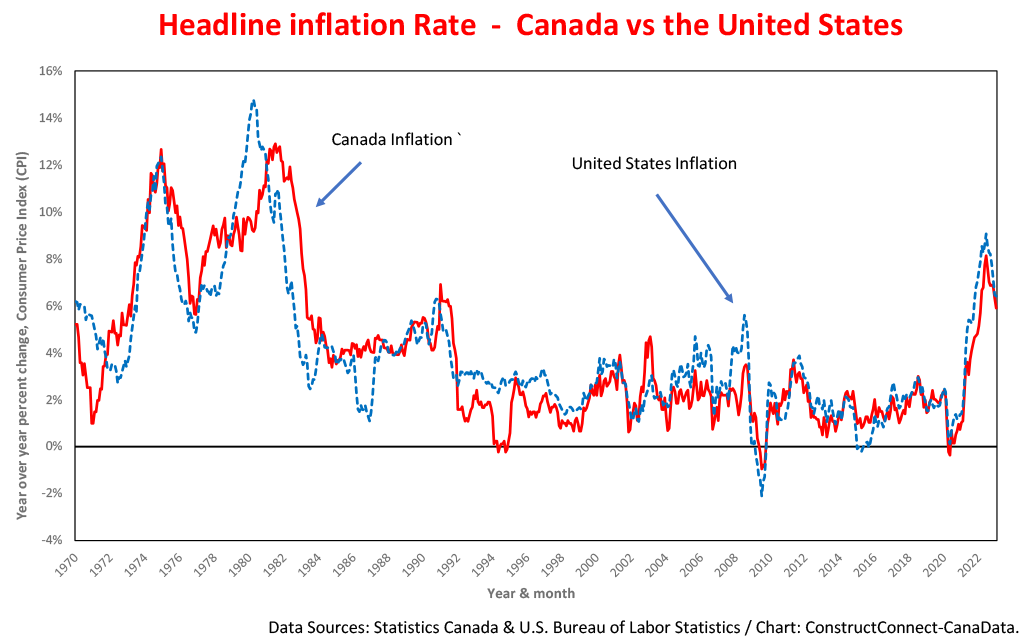

Inflation in Canada and U.S. in sync

Focussing on consumer prices in North America, as the chart illustrates, headline inflation in Canada tends to track the United States with a variable lag. In the late 1970s, the lag appeared to lengthen to six months. However, more recently, i.e., since 2010, the price series have been virtually coincident.

After an extended hiatus, the impact of a post-pandemic rise in commodity prices, led by oil, caused headline inflation to hit 38-year highs of +9.1% in the U.S. and +8.2% in Canada, in June, 2022. Given that inflation in both countries has risen by about the same amount, it is not surprising that the U.S. Federal Reserve Board and the Bank of Canada have lifted their policy interest rates in tandem by 4.2 percentage points in attempts to return inflation to its +2% target. They’ve been trying to keep price expectations well anchored by cooling consumer demand and reining in the growth of total employment.

In US, interest rates have slowed housing more; other sectors, less

Tightening monetary policy to put the brakes on growth and cool inflation is turning out to be easier said than done on both sides of the border. In the U.S., following a sharp retreat in home sales and housing starts over the previous year, the Census Bureau’s Index of Economic Activity ticked up to a six-month high in January, while total employment increased by a solid +517,000 jobs.

After retreating to a recession-signaling 48.4% in December the ISM Services Purchasing Managers Index rebounded to 55.2% in January. In addition, the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report says that the number of open positions rose by +5.5% in December following back-to-back declines in October and November. Consistent with the uptick in the JOLTs and the ISM Services PMI, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, the Federal Reserves Board’s preferred inflation gauge, ticked higher in January after trending lower for six consecutive months.

Bank of Canada sees excess demand

Nor is the Canadian economy slowing down as quickly as the Bank of Canada wants. Over the past six months, the economy has added +301,000 jobs, just slightly more than the +296,000 it added during the same period twelve months prior. Consistent with this strong jobs growth, the Royal Bank reports, in its Consumer Spending Tracker, that shoppers’ purchases are “holding up” and “higher debt servicing costs and lower real wages have yet to induce a pullback in discretionary spending”.

Regarding inflation, the governor of the Bank of Canada, Tiff Macklem, recently stated in his remarks to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance that “inflation in Canada has eased but remains high” and, as the job numbers indicate, the Canadian economy “remains overheated and clearly in excess demand”. The Governor acknowledged that interest rates take time to work through the economy.

Sustained growth + sticky inflation = higher interest rates

Given the persistent strength of employment, the lingering pattern of above-target inflation in both countries, and recent comments by the Chairman of the Federal Reserve and the Governor of the Bank of Canada, we expect monetary authorities to maintain and probably increase pressure on their policy brakes into the second half of this year. This prospect heightens the risk of a further slowing of residential construction on both sides of the border and increases the likelihood that overall growth will start to contract mid-way into 2023.

John Clinkard has over 35 years’ experience as an economist in international, national and regional research and analysis with leading financial institutions and media outlets in Canada.

Recent Comments