Much of my work-related conversation over the past year-plus has concerned the preponderance of mega-sized construction projects being green-lighted in the United States. A ‘mega’ is defined as a project carrying an estimated value of a billion dollars or more.

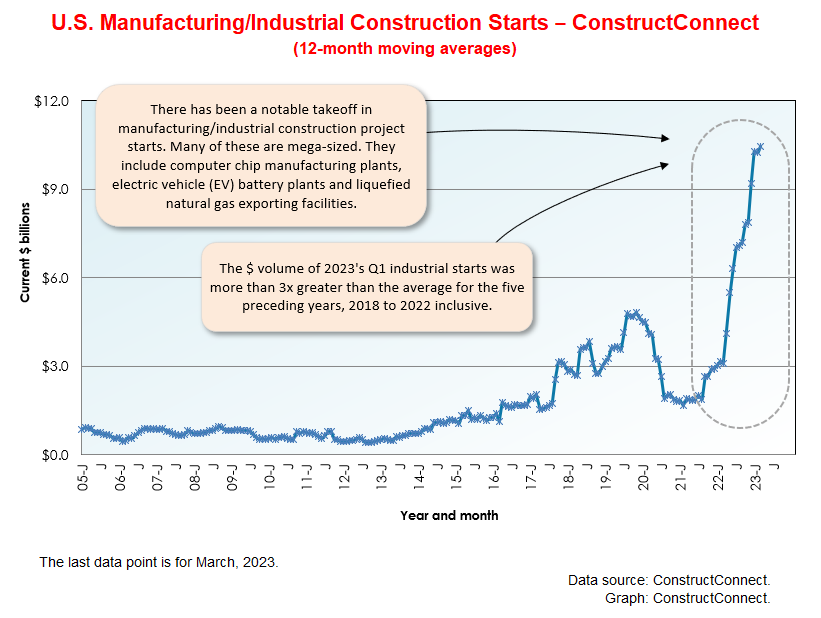

Spurred on by government incentive measures, a desire to bring jobs back to America from overseas, and target dates for drastically reducing carbon emissions, there has been an explosion of activity in ‘starts’ on industrial/manufacturing projects, as is captured in Graph 1 below.

Spurred on by government incentive measures, a desire to bring jobs back to America from overseas, and target dates for drastically reducing carbon emissions, there has been an explosion of activity in ‘starts’ on industrial/manufacturing projects, as is captured in Graph 1 below.

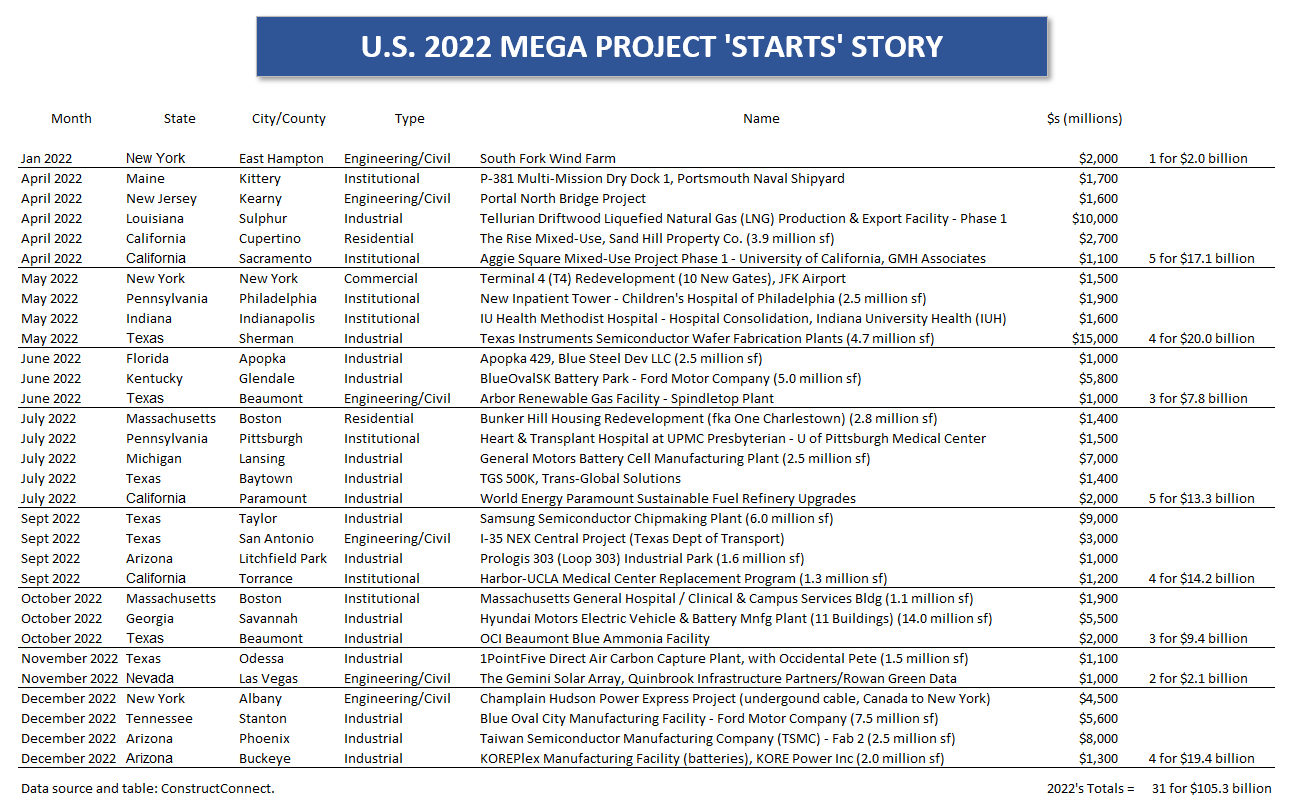

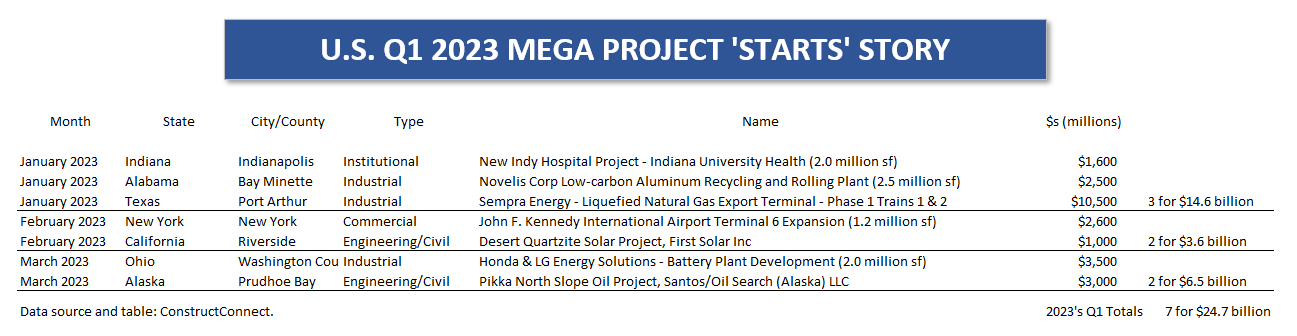

2022’s ‘mega’ project starts are laid out in Table 1 and Q1 2023’s, in Table 2. A perusal of the lists in both tables reveals the wealth of groundbreaking activity that has been taking place in new electric vehicle production plants, related battery plants, chipmaking facilities, and in the petrochemical area. Energy projects including LNG exporting sites, ammonia extraction, and carbon capture and storage are, in data terms, placed in the industrial type-of-structure category.

The story of the upsurge in manufacturing capital spending has finally caught the eye of the mainstream media. Just one example of the attention now being given to the subject is the piece titled U.S. Manufacturing Boom has a Real Estate Problem that appears in a Reuter’s feed.

The purpose of my article today, however, is to point out that, despite what my opening paragraphs may suggest, the new era of mega projects that we are currently seeing isn’t just confined to the one type-of-structure category. It is considerably more diverse.

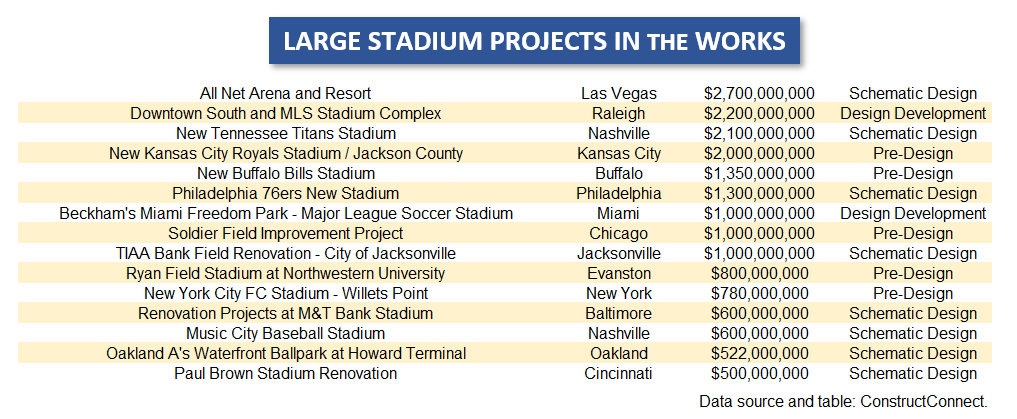

Table 3 sets out an array of mega-sized and somewhat smaller, but still huge, projects discovered when I accessed ConstructConnect’s research vault on stadiums that are in the works, to one degree or another. I hesitate to use the word ‘upcoming’ because Table 3 includes projects that are speculative and contemplated, as well as ones that are proceeding with working drawings, but also probably a few that may fall by the wayside, for a while at least.

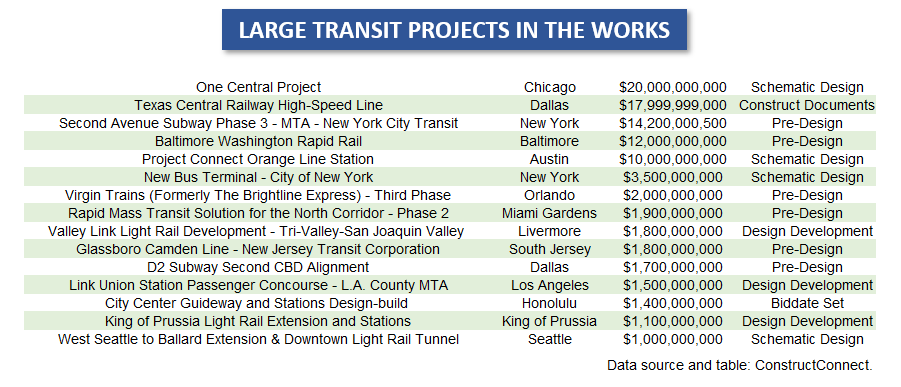

Table 4 does the same for transit projects. Furthermore, Table 4 leaves out several of the all-time largest projects that under consideration. Heading such a catalogue would be a ribbon cutting for a hoped-for commercially-viable (and not just pilot project) hyperloop. The estimated dollars associated with hyperloop construction are immense and will have a profound impact on the starts statistics when one is finally initiated.

The mega project story in Canada has, so far, not been comparably upbeat. There’s been a new EV battery plant commitment in Windsor and Ottawa has wooed Volkswagen, with a ton of subsidy money, to build a plant in St. Thomas Ontario. But Canadian mega projects are more likely to arise in the resource sector (e.g., more potash mining in Saskatchewan), during the next round of commodity price spikes.

By the way, there’s an aspect to mega project construction that should not be brushed aside. Historically, as a class, they haven’t had the best track record for smooth progression from twinkle-in-the-eye to completion. There are multiple examples (e.g., California’s bullet train) of stretched out opening dates and anxiety-inducing cost overruns.

The logistic problems of acquiring materials, manpower, and regulatory approvals are magnified exponentially when the dollars climb into the stratosphere.

Graph 1

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Alex Carrick is Chief Economist for ConstructConnect. He has delivered presentations throughout North America on the U.S., Canadian and world construction outlooks. Mr. Carrick has been with the company since 1985. Links to his numerous articles are featured on Twitter @ConstructConnx, which has 50,000 followers.

Recent Comments