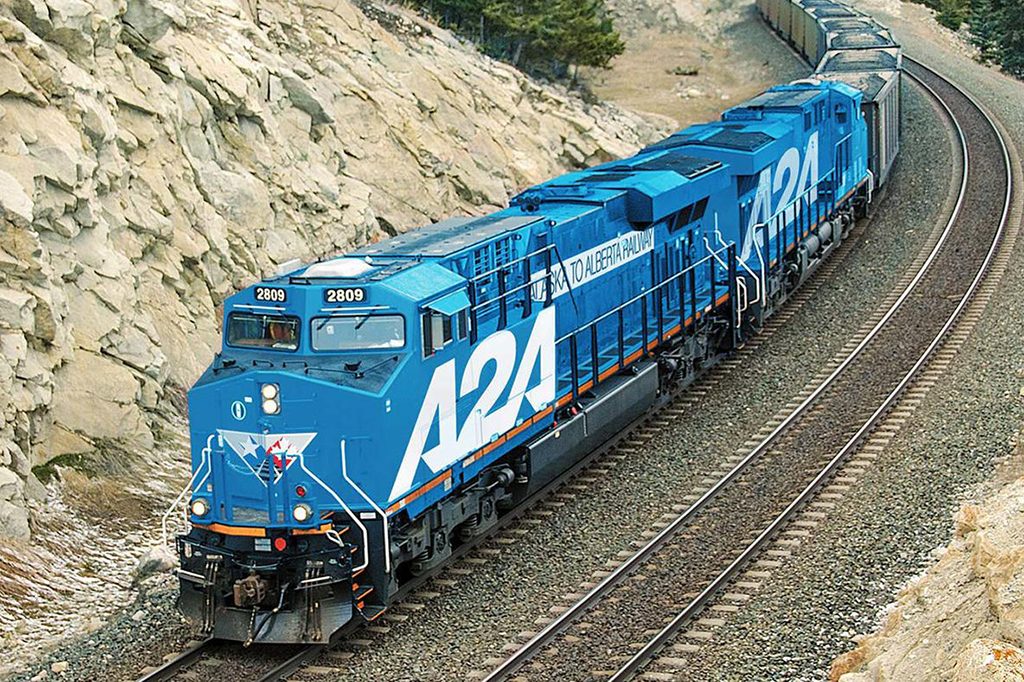

As Alberta faces challenges to move oil by pipeline to Canada’s west coast, the Alaska–Alberta Railway Development Corporation (A2A Rail) has been working since 2015 on plans to build and operate a new 2,400-kilometre railway connecting the existing Alaska Railroad to northern Alberta. As envisioned, the $17-billion project could connect all of North America to global markets, through Alaska tidewater ports.

It’s no pipe dream. A2A Rail has already assembled a team of more than 40 people and invested almost $60 million in the project. In June, the company announced that it had reached an agreement with the Alaska Railroad Corporation to develop a joint operating plan to identify the work required to upgrade and extend the 825-kilometre Alaska Railroad mainline which currently runs between Seward, near the coast, to North Pole near Fairbanks. The two companies will jointly apply to the Alaska Department of Natural Resources for a right-of-way guaranteed under state law for a rail connection to Canada.

A2A’s chief operating officer, Mead Treadwell, notes that the economic success of the project doesn’t depend entirely on moving oil products by rail. However, under a study commissioned by Canada’s Van Horne Institute (VHI) and released in 2016, the government of Alberta asked VHI to examine the viability of moving bitumen on a purpose-built railway through Alaska.

“Our operating plan considers the potential to move a million to a million-and-a-half barrels of bitumen per day, among other shipments,” says Treadwell. “The long and the short of it is that ports in Alaska’s Cook Inlet have already been exporting oil in one form or another since the early 1960s. Ports in the area export to refineries as far away as Taiwan.”

The rail project would consist initially of a single rail line with sidings that would allow trains to travel in both directions. Of the $17 billion construction budget, $14 billion would be spent in Canada.

“It’s basically a large civil construction project that would include a rail corridor of about 500 feet wide across a route that is relatively straight and relatively flat,” says Treadwell. “It would cross some areas of permafrost, though not many and a few areas of wetlands and would involve some tunneling and bridging.”

The project would use steel rails, likely incorporate concrete ties and require transportation of a large amount of gravel ballast. It would also require construction of switching yards, water and wastewater facilities, and installation of power lines and fibre optic cable.

The current proposed route of the A2A would incorporate existing railway connections in Canada and would generally head along a southeasterly route through Yukon, Fort Nelson in northeast British Columbia and finally connect with Fort McMurray in Alberta.

Treadwell foresees huge economic benefits for communities along the route, including construction, operations and maintenance jobs, new opportunities to deliver metals and minerals to markets, and cheaper goods both entering and leaving those communities. A2A is also engaging directly with each of the affected communities and First Nations, offering them equity in the project and proposing joint ventures involving construction and railway operation.

The project still needs to clear regulatory hurdles in both countries. In the U.S., a presidential permit is required for the proposed railway to extend across the border. Once a presidential permit is issued, A2A would work with the U.S. Surface Transportation Board and comply with the requirements of the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act to seek necessary permits and permissions. In Canada, the next step would involve the formal determination of the size and scope of any environmental assessments regarding the project.

“All of that work is stepping up as we try to take major permits out of the way and derisk the project for potential investors,” says Treadwell. “If we could begin construction today, we’d be looking at a three- to four-year construction project.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed