The Federal Reserve and the Bank of Canada have both held the line on interest rates lately. But neither has sworn off the possibility of raising them more at some time in the future.

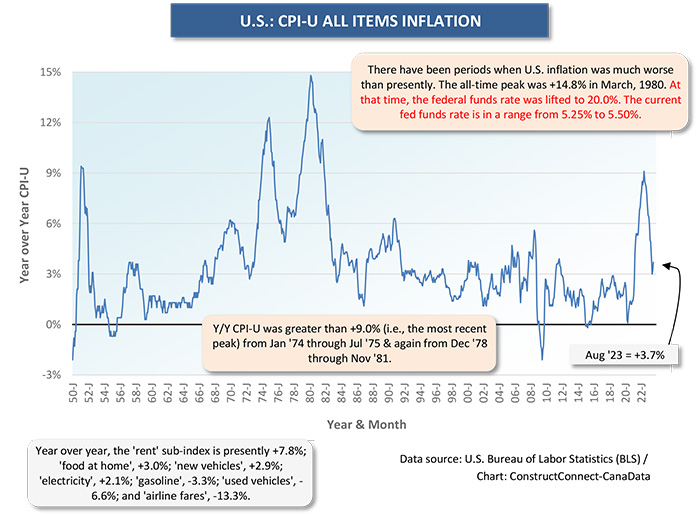

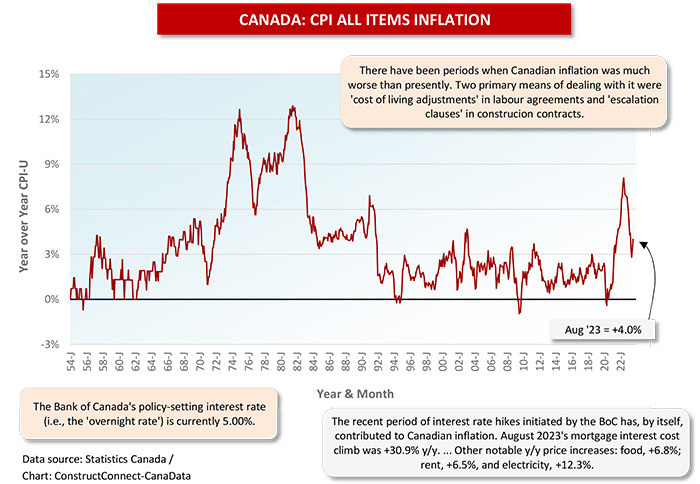

The Fed’s federal funds rate is in a range between 5.25% and 5.50%. The BoC’s overnight rate is sitting at 5.00%.

Neither central bank is yet convinced that its nation’s inflation rate has been sufficiently suppressed.

Neither central bank is yet convinced that its nation’s inflation rate has been sufficiently suppressed.

In August, the Consumer Price Index for urban dwellers in the U.S. was +3.7% year over year; in Canada, the CPI was +4.0% y/y. In both instances, the y/y advances were a bit more rapid than in the previous month.

Contractors won’t be totally comfortable with their prospects until rates, as set out in official statements, stabilize; even better, if there are indications rates are about to descend. The tea leaves are suggesting the settling down of rates may not begin until mid-2024, a more distant target date than earlier anticipated.

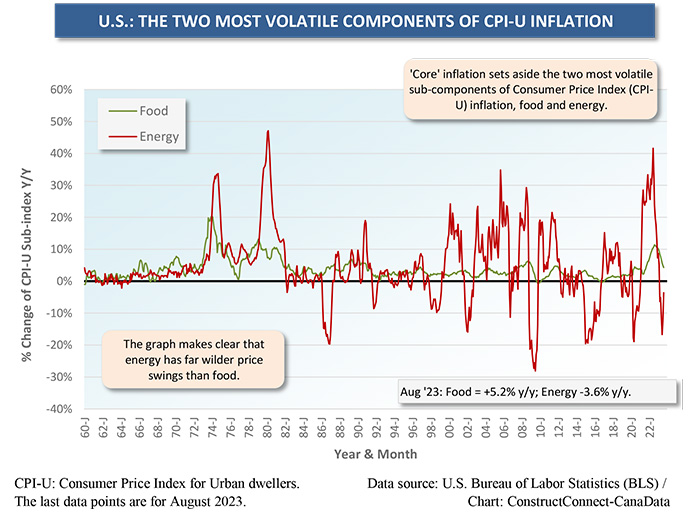

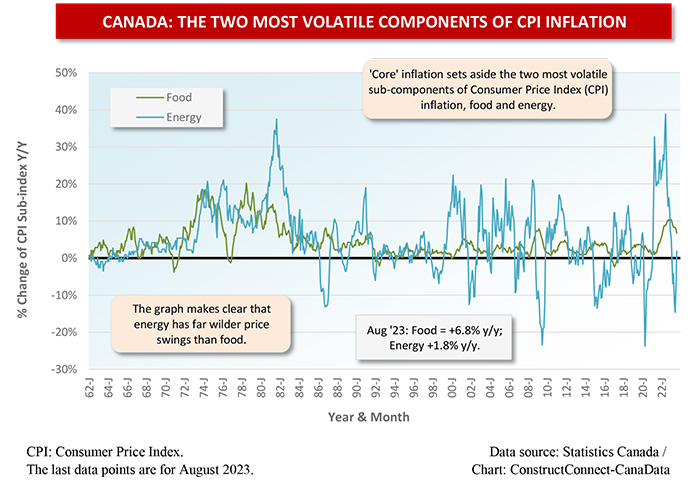

The inflation topic often sidesteps into a discussion of ‘all items’ versus ‘core’. The reason is because the latter excludes two sub-categories of surveyed consumer purchases that have track records of extraordinary pricing volatility: food and energy.

Graphs 3 and 4 record the long-term history of food and energy inflation for the U.S. and Canada. It’s clear that while the year-over-year price changes for food can sometimes be dramatic, they nevertheless nearly always fall well short of the histrionics that can be displayed by energy prices.

There’s a key question to be answered. How effective can central bank policy relating to interest rate adjustments really be in combating radical price swings in rogue areas like food and energy?

Food Prices Separate from Interest Rates

Many instances of food price volatility are tied to random events. Drought in the prairie regions of Canada is limiting durum wheat production and sending prices on an upwards trajectory.

Pasta prices in Europe have been stressed by crop damage due to bad weather and supply reductions resulting from the Ukraine-Russia armed conflict.

In combating food inflation, interest rates are trumped by extreme weather and blows delivered by shocking geopolitical events.

Energy Prices Separate from Interest Rates

In energy pricing, it’s the global marketplace that sets the price of oil. For much of the world, the Brent crude yardstick is determined by the amount of supply made available by OPEC (especially Saudi Arabia) and Russia. Saudi Arabia and Russia have recently made cuts to output, sending the price of their barrels above $90 USD.

The North American price for oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), never deviates from Brent crude to any extreme degree. If too big a price gap were to develop, North American producers would send tankers full of output to new clients overseas.

The price of domestic gas can (and currently does) deviate significantly from what is charged in many foreign markets. Until recently, in North America, natural gas reached customers only by pipelines that ended at ocean coastlines. A whole new segment of the industry devoted to shipping liquefied natural gas (LNG) anywhere on the planet has made international price watching more relevant.

August’s price of electricity as a subset in U.S. CPI-U was +2.1% y/y; in Canada’s CPI, +12.3%. The coming demands to be placed on electric power capacity as a means to achieve net zero carbon emissions over the next decade or so would seem to guarantee that significant relief in pricing will not be forthcoming.

Nowhere in this consideration of the influences on energy prices do interest rates play a major role. Some weight can be given to the notion that by applying brakes to the overall U.S. economy, and with China no longer as big a factor in driving global economic growth, there’s the possibility that energy prices may moderate. However, this smacks of wishful thinking.

(China has a host of problems relating to a moribund real estate sector, consumers that would rather save than spend, a declining working-age population, and an absence of foreign visitors.)

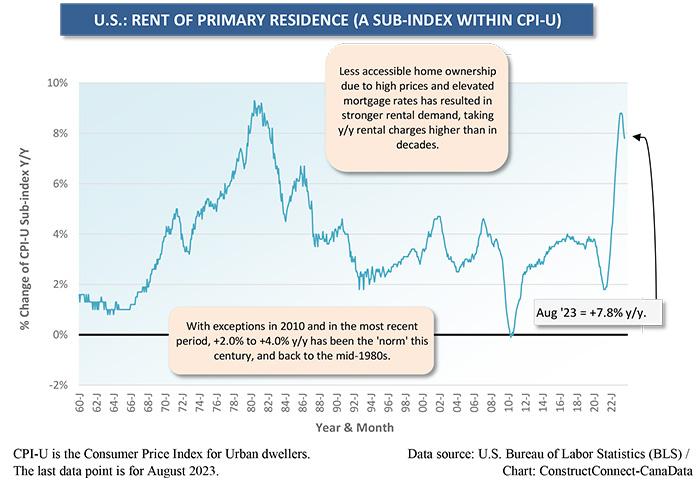

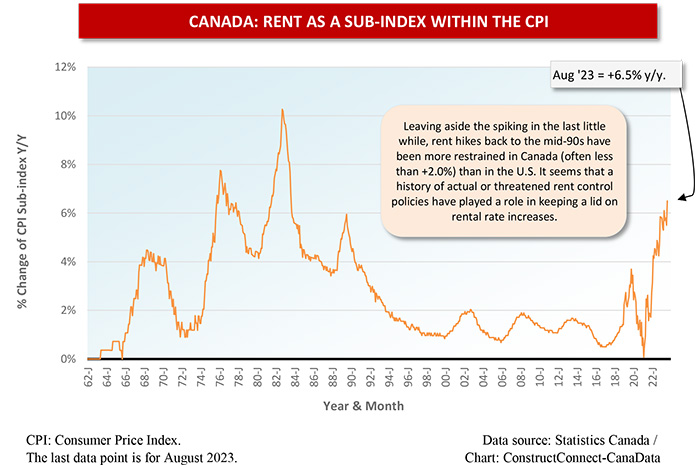

Rent Hikes as a Result of Elevated Interest Rates

As for the year-over-year mid- and post-pandemic spikes in rental rates in the U.S. and Canada, shown in Graphs 5 and 6, they are an offshoot of the higher interest rates that have made buying residential real estate more expensive.

Prospective buyers who can’t see their way to making down payments, plus managing more onerous mortgage payments, have been settling for less, in other words rental properties.

With respect to the rent component of inflation, central bank tightening is counterproductive.

A Desire to Move On

All of which brings the conversation to its most salient point. There’s a case to be made for shifting away from the obsession with restrictive monetary policy that has prevailed over the past year and a half.

As the foregoing argues, it’s not readily apparent that some crucial aspects of inflation are controllable by grand interest rate gestures.

Coming out of one of the nastiest periods in economic history, the COVID era, there’s every reason for business confidence to be strong. Also, there are other big issues to tackle, such as finding adequate numbers of skilled workers to tackle high-priority jobs.

Rather than trying to interpolate meaning from every word uttered by the Fed or the Bank of Canada, there are a great many people who would like to see the economy move on to other matters with more optimistic underpinnings.

Graph 1

Graph 2

Graph 3

Graph 4

Graph 5

Graph 6

Alex Carrick is Chief Economist for ConstructConnect. He has delivered presentations throughout North America on the U.S., Canadian and world construction outlooks. Mr. Carrick has been with the company since 1985. Links to his numerous articles are featured on Twitter @ConstructConnx, which has 50,000 followers.

Recent Comments