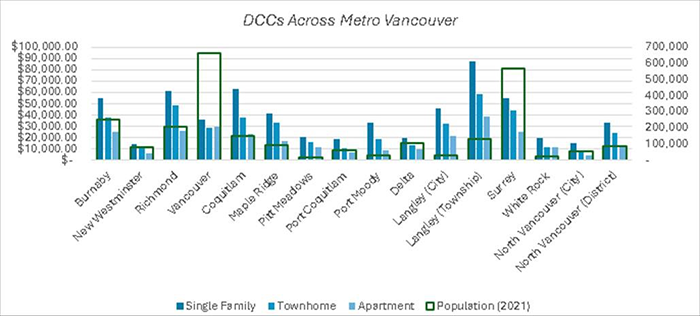

Development cost charges (DCCs) across the Metro Vancouver and regional district are putting many housing projects on hold, compounding a troubling shortage in the region.

From information collected over the past year, the Homebuilders Association Vancouver (HAVAN) concludes more than 73,000 homes in Metro Vancouver remain unbuilt because of the “accumulation of all the charges” including fees introduced under Bill 46, the Housing Statutes (Development Financing) Amendment Act, last year.

“It is another thing on the list of layers of charges that are making these projects non-viable,” says Wendy McNeil, acting CEO of HAVAN.

Many B.C. municipalities are facing development pressures that require new infrastructure, leading to increases in development fees and charges.

In municipalities such as Burnaby and the District of North Vancouver, the new DCCs account for five to 10 per cent of the total DCCs, according to HAVAN.

Overall, charges, levies and fees from government can add 20 to 30 per cent to the cost of a home, depending on home type, the association states.

“We understand the need for infrastructure…it is part of municipal growth but the reliance on it just to pay for new development is really tough,” says McNeil.

The association’s recently released report titled Development Finance: New Legislation, New Charges, and the Cost of Delivery Crisis highlights the soaring costs of building homes in Metro Vancouver and the impact of Bill 46.

The bill introduced charges as a development financing tool to help municipal governments cover rising capital costs such as fire protection, police buildings and solid waste and recycling facilities.

It also introduced Amenity Cost Charges which cover such things as new community and recreation centres, day cares and libraries, McNeil says.

The tab for the DCCs on a 4,000 square foot home in Metro Vancouver are just under $40,000 while townhome units can be as high as $27,000. Municipalities with larger populations charge even higher DCCs.

McNeil says with so many units on hold, construction costs are rising, undermining affordability.

“It’s not just a housing supply crisis; it is a housing delivery crisis.”

The homebuilders association reports in Surrey about 44,000 homes are on hold. The numbers are close to 15,000 each in Coquitlam and Vancouver.

“At a time when we desperately need housing, this is unacceptable.”

StreetSide Developments BC has about 6,000 multi-residential units in the pipeline and while it has not delayed projects because of DCCs yet, that could change because revenues are not going up and housing sales are down.

“There is a limit to what we can absorb,” says Jonathan Meads, vice-president of StreetSide.

He says deferring DCCs for a year or two or longer on sizable highrise residential projects would help the industry and still ensure municipalities get the money they need for infrastructure improvements.

Currently more than a dozen developers including StreetSide are asking the Metro Vancouver Regional District’s Board of Directors to defer the DCC implementation for two years.

Meads adds in-stream projects need to be protected from increased development charges.

Developers, particularly on large multi-family projects, spend many years creating the financing model for a project. When DCCs are added in-stream the numbers are thrown askew.

“I have plenty of projects in the middle of the approval process and now I suddenly have to layer in additional costs,” he says.

The developer points out while the government did some outreach during the process to build the framework for Bill 46, most of the development industry was not consulted.

Developers need “stability and certainty” from government, he adds.

“We don’t want meteoric changes (from government) again,” he says, because the lifespan of a large multi-residential project can be six or more years.

McNeil says consultation among all the stakeholders (local jurisdictions, developers, the communities and the province) is needed to arrive at “a more equitable solution” to pay infrastructure costs so that developers can get their shovels in the ground.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed