Vancouver city officials have been mining Seattle’s viaduct teardown project as a way to implement lessons learned on this side of the border.

The team planning Vancouver’s viaduct demolition visited Seattle last year and met with the city and Washington Department of Transportation.

“It is very clear that there are a lot of similarities,” said Kevin McNaney, director of the City of Vancouver’s Northeast False Creek Project office. “The viaducts both were built roughly around the same time in downtown areas with complex stadiums.”

The Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts are twin elevated freeways that pass between BC Place and Rogers Arena, connecting Vancouver’s downtown core to the Main Street and Strathcona neighbourhoods.

After their construction in the 1970s, opinion on Vancouver’s viaducts began to sour. Vancouver City Council voted in favour of tearing them down in 2015 after conducting technical research, 13 open houses and 38 stakeholder meetings.

According to city officials, the viaducts were intended to carry up to 1,800 vehicles per lane per hour, but currently carry only 750 vehicles per lane per hour during rush hour. Over the last 20 years, vehicle traffic into the downtown has declined by 20 per cent, while at the same time the city has grown with more jobs, residents and transportation trips overall.

1/2

GORDON SAYLE/CITY OF VANCOUVER — Vancouver’s viaducts photographed from the air by Gordon Sayle long before False Creek’s many towers popped up. The Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts were built as the start of a larger freeway project that was never completed. The city is now preparing to tear them down to open up unused space.

2/2

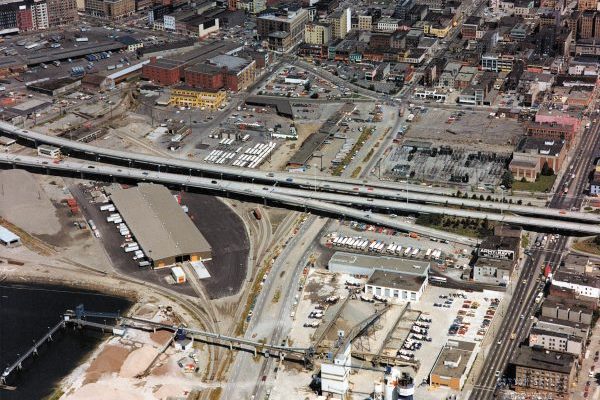

WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION — An aerial shot shows the Alaskan Way Viaduct in Seattle, Wash. which will be torn down this year. Vancouver city officials have been meeting with Seattle officials to exchange knowledge on tearing down viaducts in a busy urban area.

Research and community consultation over the last two years revealed that an at-grade road network will be more resilient to natural disasters such as earthquakes and five to 10 times less expensive for the city to maintain.

Plans also include 13 per cent more park space and the opportunity to build social housing on city-owned property.

When learning about Seattle’s endeavours, the team learned the project poses bigger challenges than Vancouver’s. Their Alaskan Way viaduct, built during the 1950s, ran for 3.5 kilometres along the city’s waterfront carrying 110,000 cars per day. Vancouver’s viaducts run one kilometre through the city and carry 45,000 km per day.

Seattle’s design-build project also has the added challenge of boring a massive, four-lane tunnel that has already faced years of delays and hundreds of millions of dollars in cost overruns after the boring machine became stuck.

“That being said, we did learn a lot,” said McNaney.

He noted the Seattle team’s strong communications system, media partners and waterfront office were especially effective. This allowed the team to clearly communicate planned traffic changes and educate the public on the future of the waterfront area.

McNaney said the major issue facing the Vancouver team is removing the viaducts with the least amount of disruption.

The easternmost parts of the viaducts can be removed and then the new area can be built traditionally, but the western end near BC Place and Rogers Arena will need a more “surgical approach,” explained McNaney. He expects the team will need to use cranes to lift portions of the viaduct out to avoid hitting surrounding towers.

He also is in communication with Rogers Arena and BC Place to co-ordinate work with major events.

McNaney added the road built following the viaducts will be a major route in and out of the city as well as a route to St. Paul’s Hospital so it must be seismically resistant.

The team plans to begin with the expansion of Pacific Boulevard into a wider two-way street and then demolition would begin. He said the earliest this would start would be 2020.

The project is expected to take nearly three years and cost around $438 million, which must be self-funded. According to city plans, with the viaducts down, room will be freed up for social housing, parks and public spaces.

“We chose a slightly longer process to disrupt less,” McNaney said.

Across the border and according to the City of Seattle, the new tunnel is expected to open in early February thanks to an innovative technique utilizing geofoam technology.

Crews can use the foam instead of dirt to support the concrete road and build ramps. The roadway is also being paved with quick-drying concrete. This reduces the time needed to transition to the tunnel from six months to three weeks.

Recent Comments