Being a highway flagger can be dangerous, but traffic control persons say they love it anyway. This Journal of Commerce column explores the services they provide and the challenges they face.

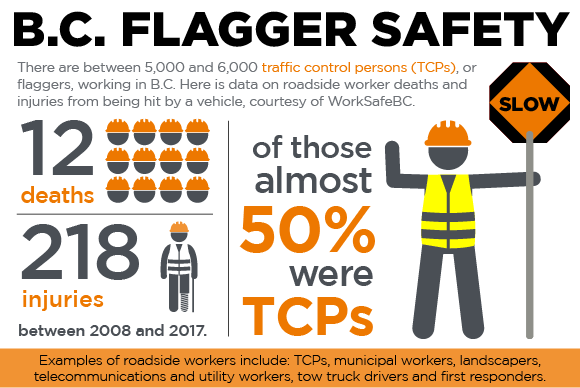

There are approximately 5,000 to 6,000 traffic control persons (TCPs), or flaggers, in British Columbia.

There are also more than 50 B.C. companies that provide TCP services to contractors.

One such company is D. Andres Quality Construction Solutions Ltd., a small family business in northwestern B.C.

“We started in 2006 with one truck and one set of signs and have grown from there,” said Donna Andres, the company’s owner and operations manager. “Now we have nine trucks and 19 employees. We started off in the Terrace area and now operate across the province.”

Andres said road and highway traffic control is challenging.

“It’s not an ordinary job,” she said. “Flaggers put their lives on the line every day. Many people don’t appreciate the dangers involved.”

According to WorkSafe BC, between 2008 and 2017 there were 12 roadside worker deaths and 218 injuries from being hit by a motor vehicle.

Of that number, almost half were TCPs.

To stay alive, flaggers need to be physically and mentally strong.

“The work is physically demanding,” Andres said. “Flaggers must be able to lift heavy objects and stay on their feet for long hours, which is much harder than it sounds.”

TCPs also need to be able to attend to small details and not let their minds wander.

“That’s an occupational hazard if you’re working on rural roads that don’t get much traffic,” Andres said.

An urban TCP has different challenges.

“The city’s visual environment is complex and changes quickly and the vehicles travel close together,” she said.

One of Andres’s employees is Jason Coles.

“I travel all over B.C. to set up work zones for companies and flag for them,” Coles said.

Despite his 12-hour work days, he loves everything about his job.

“I get to play in traffic,” he said with a laugh, “and I enjoy protecting contractors and motorists on our highways.”

Coles has had many near-misses but has never been hit or injured.

When I ask them if they’d seen the signs down the road, they say ‘What signs?

— Jason Coles

D. Andres Quality Construction Solutions Ltd.

“Few motorists pay attention to traffic control signs,” he said. “Cellphones are the biggest distraction. The worst offenders are professional truck drivers and the police.”

Coles said young female drivers seem to be the worst for speeding and not paying attention.

“I’ve had many close calls with young woman drivers speeding right at me,” he said. “When I ask them if they’d seen the signs down the road, they say ‘What signs?.’”

The BC Construction Safety Alliance is the WorkSafeBC-approved trainer and certifier of TCPs in the province.

Aspiring flaggers take a two-day course that combines classroom and practical training, after which they must pass a written exam attaining at least 80 per cent and a practical evaluation where they need to get 100 per cent.

Sarina Hanschke, founder of Vanguard Road Safety Network Ltd. in Surrey, B.C., said traffic control should require more training.

In fact, she said, it should become an occupation where apprenticeship applies, like such trades as plumbing, carpentry and welding.

“The job is less dangerous than it used to be, but tragedies are still too common,” said Hanschke. “To change that, more training is required.”

If the occupation becomes apprenticeable in B.C., it would be the first in North America.

The road to becoming such an occupation in B.C. is long and steep.

The first step is submitting a New Training Program Request (NTPR) to the Industry Training Authority (ITA), which co-ordinates B.C.’s skilled trades system.

“The program request is the first of a two-step process,” said Cory Williams, director of the ITA’s program standards and assessment. “Step two is an Industry Needs Analysis.”

In the NTPR, the applicant needs to provide the evaluation committee with evidence, including letters of support, of having consulted with a broad cross-section of the industry in question.

“The committee needs to be assured that the applicant has the necessary industry support before going to the next stage,” said Williams.

The system is rigorous in order to discourage over-enthusiastic proponents from wasting time and money making a submission that stands little chance of being accepted.

“Look and see if your occupation is apprenticeable in other jurisdictions,” said Williams. “If not, that’s a sign you should have a Plan B. There are other regulatory bodies that provide certification, try them.”

Hanschke is currently gathering background information for the step-one application to the ITA, and expects to submit it by the end of 2019.

“I feel very confident it will be accepted, but, if not, I won’t give up,” she said. “I have a long career ahead of me and I’m not going to stop until I’ve succeeded.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed