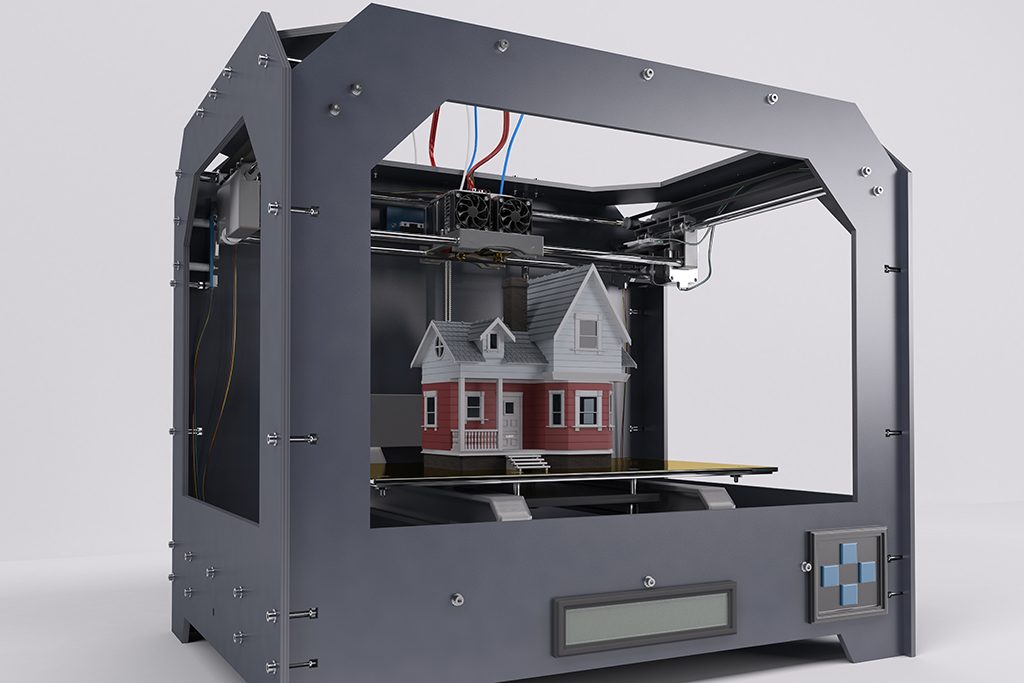

Building a house could soon be as easy as pushing a button.

B.C. scientist Paul Tinari has invented a cheap, light and fast 3D printing system that he says can form the outer shell of a four-bedroom concrete home in 24 hours at only 10 per cent of the cost of traditional construction.

Tinari explained that construction is just one of many industries that is poised to be revolutionized by 3D printing technology.

The device works by suspending a concrete-pouring nozzle in a metal cage by cables attached to four towers. The cables, controlled by a computer, move independently to precisely “print” the structure.

While 3D printing has been around for decades, Tinari believes technology has finally caught up, making it far more financially and mechanically practical.

“In the construction industry, momentum for this has been building,” said Tinari. “Companies around the world are producing 3D printers but few have been commercialized.”

Contemporary concrete printers often need heavy, delicate trusses or robotic arms, making them prone to breaking down and difficult to transport to a site. To solve this, Tinari borrowed technology from the loggers, who use cables to guide heavy logs down from mountains.

“The hardest part was the software as we had to compensate for vibration and sagging,” said Tinari. “Once that was sorted out it is a simple, light and effective system. One-tenth the price as other systems, quick to set up and take down in remote areas.”

The printer prototype was created with funding from the Civilian Advanced Research Projects Agency, owned by entrepreneur Kathleen Staples. Tinari is still waiting to have the printed structures officially strength-tested before permits can be issued to build in various jurisdictions, but he is confident that the structures won’t only pass but exceed the strength of traditional structures.

“Tests so far indicate that the 3D-printed walls are stronger than poured concrete,” he said, noting he and his team are experimenting with a proprietary concrete mix that weaves in carbon fibre, scrapping the need for rebar.

Tinari, who called 3D printing his first love, has been tinkering with the technology since the 1980s when he consulted for NASA. Back then, one needed massive supercomputers working for hours and hours to run a printer that can now be controlled on a single laptop. One could also only print a handful of materials. Now, 3D printers can handle printing thousands of materials.

“You could even print a house out of chocolate,” joked Tinari.

Tinari chronicled the history and possible future of 3D printing in his book “The Joom Destiny”. He predicts that soon 3D printers will be common in almost every home and industry.

He noted that his device could be especially useful for rapidly addressing affordable housing needs in the Lower Mainland, rebuilding housing after natural disasters in a matter of days rather than years, and rebuilding unfit housing on remote First Nations land where access is difficult.

Tinari added that the technology could also drastically address the skilled labour crunch in the construction sector by requiring far fewer workers. But he was quick to address fears the printers would destroy jobs.

This happened in the previous technology revolution when it came to horses,” said Tinari. “Thousands in the horse maintenance industry lost their jobs, but they got new jobs in the rapidly growing car industry. Yes, lots of people will lose their jobs but those will be replaced with higher level jobs in the 3D printer printer industry. There will be more jobs created than destroyed.”

Tinari’s next step is to start producing housing in June on First Nations reserves which do not require a building code.

“We are going to prove the technology is viable, invite inspectors, and show that these are superior to traditionally built structures,” said Tinari. “We are still using the same methods that the Romans did in construction. I thought I should apply my knowledge and innovation to the construction industry.”

Tinari was born in Connecticut but moved to Montreal when he was five years old. He graduated from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. in 1981 with a degree in Engineering Physics and later achieved his Ph.D. in Fluid Mechanics from the von Karman Institute in Brussels. His research involved developing the heat transport system for the NASA Space Station.

Recent Comments