When Louis Michel drives around the old city of Quebec with friends he often has “a little story here and there” to tell about the 4.6 kilometres of centuries-old stone walls and gates of the fortified city.

That should be no surprise. As project manager for Parks Canada in Quebec City, Michel oversees the preservation and maintenance of the stone and brick fortification.

This year Michel has a multi-million program on tap which incorporates repairs and restoration work to the Saint-Louis Bastion, Saint-Jean Bastion and the Ursuline Bastion as well as walls at Montmorency Park.

The project manager says long before the work starts one of the challenges is working out a schedule that is sensitive to shopkeepers and other businesses in a city where the old walls are a big part of tourism — the lifeblood of the city.

“Most of city’s festivals and activities are centred around the fortifications, so obviously the drawback when we want to do work is we are right where they don’t want us to be,” he explains.

At times event organizers are alerted of work schedules two years in advance so they can move festivities elsewhere, he says.

While most of the fortification visible to passersby was built around 1840, some of the earliest walls — often covered over in later generations — are still intact and date back to the 1700s.

Michel says prioritizing projects is done by Parks Canada through a combination of annual visual inspections and a comprehensive evaluation every fifth year, assessing such issues as water and drainage problems, safety concerns, mortar integrity, wall inclination and cut, popping or delaminated stones.

Replacement stones are cut to the same dimensions and then abraded and burned to score “the perfectly planed finish,” he says.

Sandblasting prior to mortar pointing gives the wall an even finish, he explains.

Even if fascia walls are in good condition, the core interior walls might be crumbling. If sand pours from small holes drilled through the fascia to the core, then the wall can be partially disassembled for inspection. Stones are numbered and catalogued as they are removed to ensure they are reassembled in the same position.

1/3

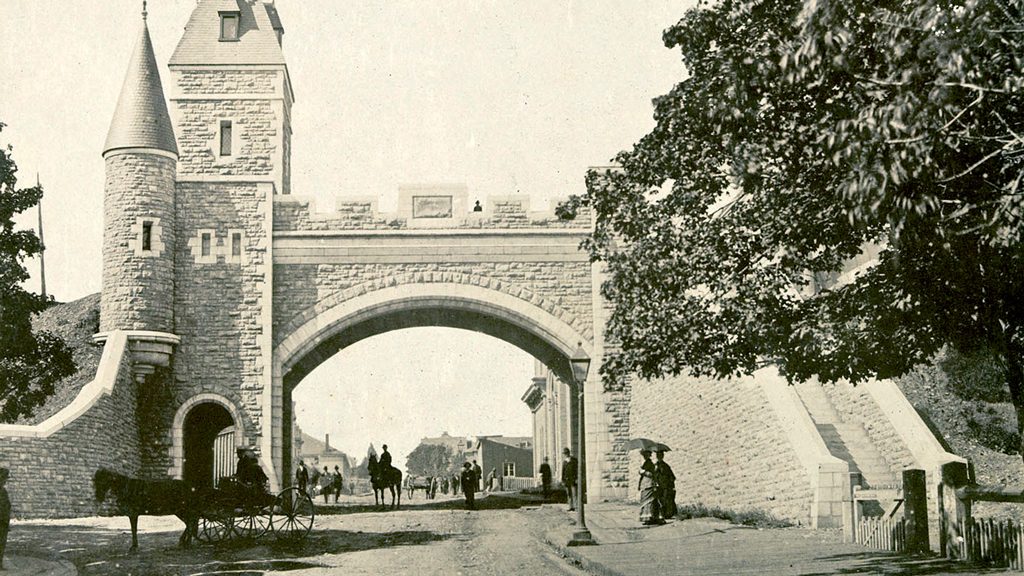

PARKS CANADA — Over the years several portions of Quebec’s fortified city, including the Saint-Jean Bastion, seen here. Further work is slated for several areas of the walls and gates.

2/3

PARKS CANADA — A crew member undertakes interior work at the Caponniere fortification in 2016. A multi-million program is slated to take place in Quebec that incorporates repairs and restoration work to the Saint-Louis Bastion, Saint-Jean Bastion and the Ursuline Bastion as well as walls at Montmorency Park.

3/3

PARKS CANADA — Pictured is the exposed inner wall of the Caponniere portion of the fortifications of Quebec undergoing work in 2016.Type N mortars — sometimes adapted — are often specified, although Type S mortars are used for higher loads.

“In the past 30 to 40 years we have tried many types of mortars, none of which is perfect,” says Michel, noting Quebec’s harsh winter climate “is tough on mortar.”

The standard is a premixed blend of one-part lime, one-part portland cement and six parts sand.

With only a small team of masons, Parks Canada subs out the work to contractors skilled in old-world masonry.

“When I talk to my people, the masons, and even the contractors I say this work comes with the pride of working on the fortification,” he says. “Obviously building a supermarket can be nice work…but doing the upkeep of the fortifications (a UNESCO World Heritage site) definitely brings an additional level of pride in what you do.”

Most of the walls are comprised of grey sandstone quarried from the Sillery cliffs in suburban Quebec City. Limestone is from the Montreal area and a quarry 60 kilometres west of Quebec.

Michel says today’s repair and restoration program is “quite different” from the approach in the late 19th century when some sections of the fortification were untouched until “they were almost falling apart.”

Restoration techniques have evolved and masons have learned from past mistakes such as replacing original sandstone with granite, which was an incompatible marriage.

Worse yet, in the 1940s, deteriorated limestone and soft mortars were replaced with high-strength modern concrete “at times shaped like a wedge” in the backing wall which pushed out the top of the wall, says the project manager. Concrete, furthermore, can cause cracks and fractures in the softer sandstone during expansion and contraction.

Not all Michel’s discoveries behind fascia walls are unpleasant.

Two summers ago a section of the original French wall near the Citadel was revealed.

“It was within the core of the new British wall built in 1840,” he adds.

Jo-Anick Proulx, cultural resources manager with Parks Canada, says when archeological finds such as the old wall are made, the wall is repaired and then protected, sometimes with a geotextile membrane and then documented for future generations.

Michel says it is increasingly difficult to secure subcontractors with masons skilled in the old-world craft because there is a lot of restoration work in Quebec, including at the Citadel and the provincial parliament buildings.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed