A 227-kilometre-long, all-season gravel road that would connect a mineral-rich region in the Northwest Territories (N.W.T.) to a deep-water port and Arctic shipping stop in Nunavut has received renewed life, thanks to a recent $21.5-million infusion from the federal government.

The Kitikmeot Inuit Association (KIA), which is overseeing the ambitious project, is now assembling a team to re-start the environmental assessment process that was shelved two years ago due to lack of funding.

The road would create jobs and give a substantial boost to the economy of the northern region by linking the Northwest Passage with year-round access to the interior of the Slave Geological Province, an area that straddles the boundary of the two territories and already includes several working diamond mines.

The road would eventually be connected to the terminus of the existing Tibbett-Contwoyto winter road that connects to Yellowknife, N.W.T. providing access for the Kitikmeot region to the national highway system.

The N.W.T. government is looking to replace the Tibbett-Contwoyto winter road with an all-season road. When that project is completed, the two thoroughfares would make for the first permanent, land-based transportation link between Canada and any part of Nunavut.

“This would be enormous for our region, but it would also benefit the rest of the North, and Canada as well,” says KIA executive director Paul Emingak. “It needs to happen.”

Reports indicate that the road, along with the port project and development of deposits in the Slave Geological Province, would boost Nunavut’s GDP by $5.1 billion and Canada’s by $7.6 billion over a 15-year period.

“There are several reasons why this project is important to Nunavut,” explains Emingak. “Our territory needs a major boost in economic development to provide opportunity to our young, growing population.

“For Nunavut’s economy to grow and diversify, we need to attract investment. However, investment in our territory is held back in large part by a lack of infrastructure that is available to support economic development.”

Emingak says KIA intends to use the federal funds to cover the cost of getting the road as well as the Nunavut Grays Bay port project “shovel-ready” which means that the environmental assessment process will be completed, and the detailed engineering design will be at a level that allows the project to be tendered.

“We expect this process to take two to three years once we fully restart the environmental assessment.”

The project’s environmental assessment was initiated in 2017 but was suspended due to lack of funding in 2018.

“The next step is to assemble the team necessary to restart the environmental assessment process and to execute a field program this summer,” says Emingak.

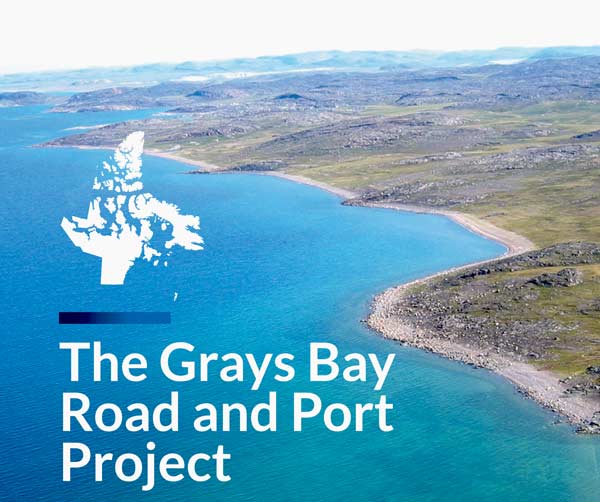

The road itself is being considered a transformation project of national significance by its stakeholders, as it would connect with a brand-new port at Grays Bay on the Coronation Gulf. The port itself would serve as Canada’s first and only deep-water port in the Western Arctic region, strategically located at the mid-point of the Northwest Passage.

While building a road north of the Arctic Circle comes with challenges, namely logistics and weather, Emingak says they can be overcome.

The plan, he says, is to start construction at both ends of the road and eventually meet in the middle. At the northern end, a staging area would be created at the port site during the summer months where building materials and equipment could be shipped in by barge. At the southern end, mobilization would have to take place in the colder months so that a winter road from the N.W.T. could be used.

“The long lead times required between staging and deployment of materials and equipment adds to the cost, as does any requirement to fly in goods that are not mobilized in a timely manner,” explains Emingak.

Weather can delay activities, especially when visibility and extreme cold are in play, and permafrost can pose additional challenges when building a road in northern Canada, he says, but construction techniques to address such issues are well-understood and have been broadly executed already at other projects.

The road would be a game-changer for the region, generating jobs, infrastructure and business opportunities for Inuit, as well as tax revenues for government, as landowners would receive royalties from projects.

The roadwork itself is expected to create roughly 1,260 full-time jobs annually during three years of construction and, upon completion, result in savings of $500 per year per person in the region.

Studies have shown that for every $1 million spent on exploration in the region, GDP increases by $518,000 and the equivalent of 5.2 full-time jobs are created in Nunavut.

“Perhaps more important, increased exploration can result in the discovery of the next generation of mining projects,” says Emingak. “This is really important because grassroots exploration has almost disappeared through vast swaths of the North.”

Two known mineral deposits in the Kitikmeot region are currently not viable because of transportation issues, but with the road in place would be economically feasible and increase Nunavut’s GDP by $739 million during each year of construction and another $800 million for the rest of Canada, notes Emingak.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed