The lack of an enforceable contract does not leave the plaintiff without a remedy. It could claim compensation on a quantum meruit basis, which means, basically, “the amount it deserves” or “what the job is worth.” The judge concluded that it would be unjust and contrary to “commercial good conscience” to allow the defendant to have benefit of the plaintiff’s work without payment.

Owner must pay for abandoning development deal

by Michael Mackay

Bond Development Corporation v. Esquimalt (Township)

Building contracts • Legal characterization of aborted contract • Developer entitled to payment on a quantum meruit basis where municipality refuses to proceed with construction and land swap deal

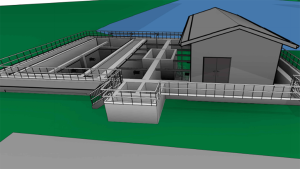

In spring 2001, the Township of Esquimalt wanted to develop a new Town Centre with a new City Hall and library. Bond Development offered to develop and build the project on some vacant land Esquimalt owned. Esquimalt would pay Bond $4,060,000 by transferring the old City Hall site to Bond and paying the balance in cash. Each party would retain an appraiser, and the average of their appraisals would be the value of the old City Hall.

On October 3, 2001, the parties entered into a formal contract which included a term that:

Bond will build the Town Centre substantially to the performance standards of the British Columbia Buildings Corporation [BCBC] for government offices as illustrated by the quality and finish of the buildings at the new Juan de Fuca Library … and the View Royal City Hall … at a cost to Esquimalt of $155.00 per ft², of a size 20,000 ft², all to be detailed in the Stipulated Price Contract. [Emphasis added.]

In spring 2002, the parties got into a dispute over the scope of work, particularly the standard of construction. Esquimalt said that the entire project had to be to BCBC standards, and with direct digital controls for the HVAC system. Bond disagreed. The parties had specifically inserted the qualification “substantially” into the agreement so that Bond would not have to comply with BCBC standards in every respect.

Bond wished to mediate the dispute, in accordance with the dispute resolution terms of the agreement, before signing the Stipulated Price Construction Contract. Esquimalt refused, and instead hired directly the contractor that Bond had introduced to the project. At this stage, the parties seemed to have “walked away from the contract.”

Bond sued, seeking compensation for breach of contract, alleging that Esquimalt had repudiated the contract by refusing to mediate. Most of the trial addressed this issue, so Justice Melvin’s reasons did as well.

First, he was not impressed by Esquimalt’s conduct. When it knew that Bond’s principal was out of the country for two weeks, and could not be contacted, Esquimalt gave notice forfeiting the agreement, and:

contact[ed] both the architect and the contractor who had been working with [Bond] to see if there was any legal basis that might interfere with them continuing with the project working directly for [Esquimalt]….

Justice Melvin also thought:

[Esquimalt’s] position … that mediation take place after the signing of contracts was, under all the circumstances, forcing [Bond] to capitulate or terminate.

Most importantly, however, Justice Melvin concluded that the dispute over the scope of work did not affect the parties’ legal position. The real issue was the contract price.

There was no enforceable agreement because the parties never agreed on a significant component of the price — the value of the old City Hall, Justice Melvin states:

The main issue, however, in my opinion relates to the consideration problem which the parties had not resolved as of June 2002…. There was, as a result, a failure to resolve the value of the [old City Hall] site – a failure of consideration of a significant magnitude.

Under the agreement, the price would be $742,350: the average of Esquimalt’s $999,700 appraisal and Bond’s $485,000 one. Because the spread was so great, the parties hired a third firm, Thibault & Company, which valued the property at $580,000. Esquimalt never agreed to any particular value.

Although the total price was agreed, the cash component was not. The cash component was a significant element of the consideration, because it determined the cash available to Bond to pay its contractor and consultants.

Liability and Damages

The lack of an enforceable contract did not leave Bond without a remedy. Bond could claim compensation on a quantum meruit basis. Quantum meruit means, basically, “the amount [it] deserves” or “what the job is worth.”

In a 1999 Alberta Law Review article, Professor Fridman noted that courts award quantum meruit damages:

…wherever they consider that, in the interests of a just and fair result, it is imperative to provide the plaintiff with some form of recovery as against the defendant in the absence of a contract between the parties and despite the fact that the defendant has committed no tort against the plaintiff.

Justice Melvin concluded that it would be unjust and contrary to “commercial good conscience” to allow Esquimalt to have benefit of Bond’s work without payment.

While developers typically risk non-payment if their projects do not proceed, and so normally would not be expecting, or entitled to, payment for aborted ones, Bond’s case was not typical. Here the parties signed an agreement in October 2001 that failed because of the subsequent scope of work dispute. In the meantime, Bond had done significant work, including retaining architects and contractors to complete the project. Esquimalt took the benefit of Bond’s work when it built the project using the same architect, plans, and contractor that Bond would have used.

Bond’s expert witness testified that, for services performed from May 8, 2001 to June 5, 2002, Bond deserved $529,167, which would be reasonable remuneration to a project manager on a project of this size.

However, Bond should only be compensated for work done after formalizing the deal in October 2001 until Esquimalt “walked way” in June 2002. After adjustments, Justice Melvin awarded Bond $222,658.91.

British Columbia Supreme Court

Melvin J.

April 2, 2004

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed