For every tonne of potash that’s mined, another two tonnes of excess salt are brought to the surface. Expensive to transport, piles of salt grow and leach into soil over centuries.

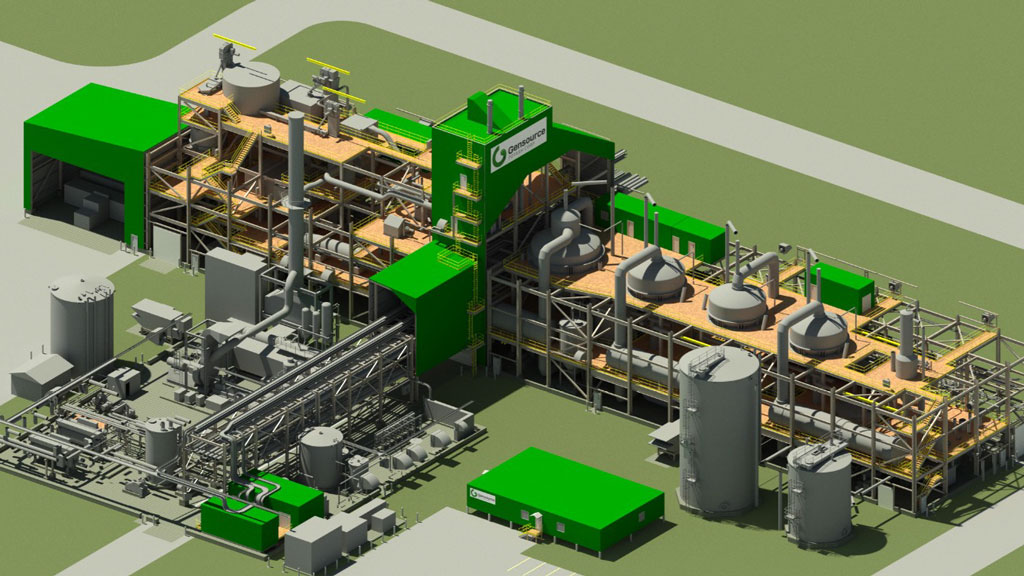

But this summer, Saskatoon-based Gensource Potash Corporation expects to start construction on a potash-producing facility in Tugaske, Sask., that’s peppered with features that are easy on the land, water and air.

“We saw an opportunity to do it (potash mining) differently,” said Gensource CEO Mike Ferguson. “We’ll do it in a saleable, efficient and environmentally sustainable way.”

He compares several of Saskatchewan’s current potash mines as using steam engine technology in the age of Tesla. The 1960s-era methods rely on dangerous, underground mining that not only brings unsaleable salt to the surface, but also uses about three times the amount of water.

As well, when the mine stops operating, it can take up to 700 years for the piles of salt to disappear. “There’s no practical way to decommission them,” says Ferguson, a mechanical engineer.

The Tugaske site, about 150 kilometres northwest of Regina, will be much smaller than a traditional potash mine: 40 acres versus about four square miles.

Production will also be notably smaller at about 250,000 tonnes of potash per year versus 2.8-million to 4-million tonnes per year at large mines.

Construction costs and timelines are also diminished, with the Tugaske facility expected to take two years to build and cost $350 million with an additional $120 million contingency account, Ferguson said. The Bethune potash mine cost $4.5-billion to build and it took a decade.

The key environment-saving feature at the Gensource mine will be its selective extraction method. “Tugaske won’t have any salt tailings. It won’t have brine ponds,” Ferguson said.

The method works by using an already saturated salt (NaCl) brine that is injected into horizontal caverns in the ore body. The brine selectively dissolves only the potash (KCl), leaving the excess salt in the ore zone underground.

The potash-rich brine is then moved via buried pipelines to be processed.

Processing is done by cooling the KCl-rich brine in crystallizers, precipitating solid potash.

The collected solids are then debrined and dried, with the NaCl brine being reheated and reinfected back into the cavern to repeat the process.

“We recycle 100 per cent of the brine,” Ferguson said.

The brine can be reused indefinitely, buttressing the claim that the Gensource model will use 75 per cent less water.

One important aspect is that brackish or groundwater can be used, thus minimizing the use of freshwater, a valued commodity in Saskatchewan.As well, Gensource, a publicly-traded company, plans to self-generate power at Tugaske.

Natural gas, not coal, will be used. Gensource expects to generate 24,500 fewer tonnes of CO2 emissions each year compared to traditional mines.

The vice-president of the Saskatchewan Environmental Society likes what he’s hearing, but said the devil’s always in the details.

“There are a few promising approaches, but until they build it and operate it, we don’t know how it will work out,” said Bob Halliday.

As a former director of Canada’s National Hydrology Research Centre, he’s intrigued by water use at the Tugaske facility.

“It could be a first in using groundwater rather than fresh water,” says Halliday, a consulting engineer. “Minimizing water use is quite a promising thing.”

He also likes the idea that waste heat from the site will be used for evaporation.

While Tugaske is a relatively small operation, Halliday is optimistic the technology can be scaled up for larger production.

Ferguson notes the technology planned for Tugaske is already being used in Utah by Intrepid Potash. “We’re not making it up,” he quipped.

When building starts this summer, Ferguson predicts 150 to 200 jobs will be created over the two-year period. Fifty long-term jobs will follow, with no underground work.

One further plus is that Gensource has a deal with HELM Fertilizers Corp.

HELM will purchase 100 per cent of Tugaske’s annual production, which will be marketed directly to HELM’s customers.

“We’re doing potash differently,” Ferguson said.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed