As winter approaches, those living in cold northern climates are focussed on retaining interior heat in homes and commercial structures. However, projections indicate more needs to be done to prepare for much hotter temperatures in future summers.

Individual home environments can be more easily controlled than larger commercial and institutional buildings. Those must monitor and maintain suitable temperatures in high volume spaces, even when occupant usage varies. Traditionally, cooling interior spaces during occasional extreme summer heat events typically falls to mechanical systems like air conditioning.

However, the future high cost and ongoing emission implications of mechanical cooling devices are coming under examination, as are the national and international standards that guide their application.

In her opinion piece published by Building Design, Susan Roaf, emeritus professor of architectural engineering at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, passionately criticizes the dominant influence of “middle aged white men in suits from Europe or the USA who are part of the HVAC establishment” and who write international comfort standards.

Why such strong language? Apart from Europeans and North Americans simply getting used to higher temperatures or specifying ever-larger mechanical cooling systems, Roaf believes a lot more can be done from a design standpoint to reduce the heating and cooling loads placed on buildings in the first place.

Typically, windows in offices and institutions are not operational and interior spaces are wide and open. It results inevitably in an over-reliance on HVAC systems to manage the interior climate all year round and around the clock.

This dependence is further perpetuated by project owners and developers who have yet to grasp the availability of alternatives, and when cities approve reports that recommend mandatory air-conditioning in new Part 3 residential buildings, as recently done by Vancouver.

Given the forecasts for increasing temperatures over the next decades, designers and project owners need to recognize that the long-term energy costs of running and maintaining such systems will increase relentlessly and that the carbon load will stress the planet.

Yet, in many parts of the world, extreme heat is part of everyday life. What can more moderate climates learn for them in terms of designing, building and retrofitting buildings as increasingly high temperatures become more common?

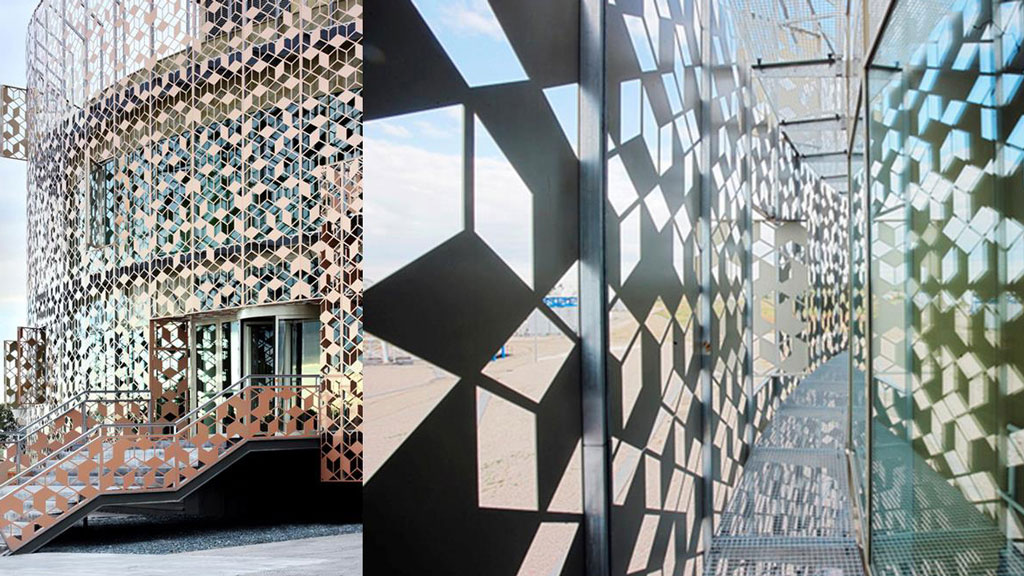

One possibility is the lattice structure such as the jaali, used for centuries in the Middle East and India.

Jaalis add more than artistic beauty. These exterior lattice screens “allow the air to circulate, protect (the buildings) from sunlight and provide a curtain for privacy,“ architect Yatin Pandya told the BBC.

Jaalis are often as thick as the building’s walls but break the window openings down into smaller components that allow the passage of light, while promoting a Venturi effect to improve passive ventilation. In some installations, the “stack effect” is used by rotating the angles of the façade bricks to minimize solar radiation.

In his 2018 study of screen shading systems, sustainable design researcher Ayesha Batool of U.K.’s University of Nottingham determined jaalis outperformed systems that deflect sunlight like brise-soleil facades and reflective glazings.

In fact, among the recommendations in the India Cooling Action Plan are passive cooling interventions such as architectural elements like jaalis, for cooling buildings and to mitigate instances where buildings and roads absorb and re-emit heat, a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect.

Screenings such as jaalis are finding their way into modern Western European architecture.

A striking example of their adoption with some European flair can be seen in the headquarters and control centre for Hispasat, the Spanish company that manages the country’s communication satellites.

This retrofit of a 1970s building features an added façade of five-millimetre sheet-aluminum panelling modules. The perforations vary in density, depending to the degree of lighting needed as well as the internal comfort of the user, reacting to atmospheric changes and changing sunsets in the facility’s vast and open location.

Everything old can be new again when designing for an over-heated planet.

There will be more on this subject in the weeks to come.

John Bleasby is a Coldwater, Ont.-based freelance writer. Send comments and Inside Innovation column ideas to editor@dailycommercialnews.com.

Recent Comments