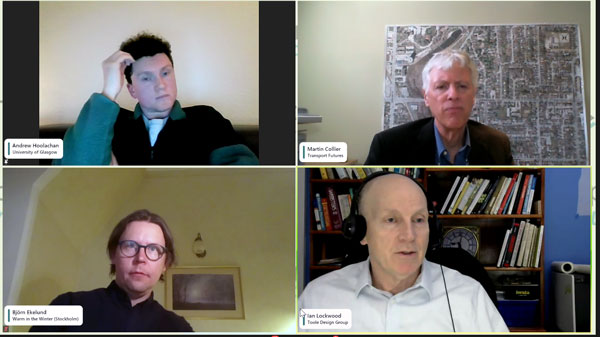

At a time when Ontario is all-in on new highways and has committed to a major spend to rehabilitate the crumbling Gardiner Expressway along downtown Toronto’s waterfront, transportation experts were singing a different tune during the third installment of the Transport Futures Highway Planning Webinar Series on March 9.

In fact, noted Scotland’s Andrew Hoolachan, University of Glasgow planning lecturer, the current informal theme song for Glasgow’s Replace the M8 campaign is the hit song by 1980s Scottish rock band Orange Juice — Rip It Up (And Start Again).

Demolishing community-stunting motorways that favour only drivers and replacing them with traditional multi-level city infrastructure that reflects social justice and environmental concerns has a proven track record around the world including in many American cities, panellists said during the March 9 session. The theme of the webinar was Replacing Highways: A Different Approach to Transportation Planning.

“Highway removals solve macro problems. It creates an opportunity to reconnect with the network which makes local trips much more efficient, it improves or lessens air pollution dramatically across the city, it lessens energy consumption, it creates a better quality of life,” said Ian Lockwood, Florida-based livable transportation engineer with Toole Design Group.

“It’s all about nurturing businesses and social interaction and the outcomes are better character, better health, more mobile choices and more vibrancy.”

Lockwood’s colleague Andrea Ostrodka, a Toole Design transit practice lead, said for thousands of years, up until the rise of the automobile, cities successfully accomplished the exchange of goods, ideas, information, labour and health care services.

“Automobiles have been pretty disruptive in terms of the way that they’ve influenced cities,” said Ostrodka.

Unlike in Europe, where highways delivered travellers between large cities but tended not to bisect them, America created interstates that entered cities and destroyed large swaths of communities.

Hastings Street in Detroit, home to a vibrant Black culture, became the ugly face of urban disruption when a major highway was built.

“It was a dagger in the heart of the Black community in Detroit,” said Ostrodka. “But it really had an effect on all of Detroit.”

Today the pendulum is swinging back in Detroit, Lockwood said, with transportation decisions that prioritize businesses and social interactions over roadways.

Other case studies Lockwood discussed included anti-highway campaigns in Chattanooga, Virginia, Oakland, Buffalo, Flemington, N.J. and Pasadena.

Typically, the discussion starts with highway mitigation through such infrastructure as elevated highways, depressed highways with bridges or caps, walls and screening, tunnels, underpasses and overpasses.

The next set of policy options includes removals – of spurs or redundant sections – then relocations and preventions.

Removals become opportunities to address city forms, auto dependency, inner city disinvestment, expensive and land-gobbling interchanges, energy consumption, city image and transit performance.

A significant new tool is the Universal Equation for Land Use and Transportation Planning. The aim is to reduce kilometres travelled, increase the modal split, increase the number of trips and reduce the average length of trips.

“Copenhagen did this. They were very automobile-oriented in the early ‘70s,” said Lockwood.

“And they used the equivalent of that equation to wean themselves off their automobile habits and dependency and create a better city, a more functional, efficient, pleasant, clean place.”

The battle over the South Pasadena Freeway took decades, Lockwood said.

Caltrans tore down numerous homes and two segments were built, north and south, but opponents refused to accept further demolitions to enable its completion.

In October 2019, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation that effectively put an end to the proposed freeway.

“That line has been relinquished and given back to the city, so that’s very exciting for Pasadena,” Lockwood said.

In 2009, Lockwood’s plan to replace a proposed major highway east of Flemington with a connected street network and integrated land use plan won ITE’s Project of the Year for its cost-effectiveness, context-compatibility and multimodal nature.

“Every aspect of this community was better by not building the highway,” he said.

Glasgow’s Replace the M8 just started during the pandemic but is picking up momentum, Hoolachan said, assisted by climate change targets calling for a major reduction in overall automobile mileage.

The M8 would be downgraded to become part of a local city centre ring that displaces through traffic.

Hoolachan said activists were surprised that the most radical among four proposed options, Rip It Up and Start Again, was favoured by 53 per cent of citizens in a poll.

He said the Replace the M8 group needs to take control of the polarized debate with effective research showing, for example, the land value capture associated with renewed city building.

“Someone has to be brave and stick their head above the parapet and say ‘no, this has to happen,’” Hoolachan said.

The next webinar in the highway planning series, taking place on March 23, will focus on financing and procurement in the current market. The DCN provides our subscribers with a 10% discount using promo code DCN23.

Recent Comments