The Baxter International campus could remain a shining example of mid-century modernist architecture or it could largely become a nondescript logistics terminal.

That’s the choice civic officials in Chicago’s northwestern suburb of Deerfield will have if they approve a redevelopment plan for the 1970s-era nine building campus, which preservation groups and even local citizens are fighting against.

There are several reasons why the office campus, which has housed medical instruments company Baxter, should be saved, say preservationists.

One is that the iconic central facilities building, which houses a 700-seat cafeteria, was one of the first buildings in the world to have cable-stayed roof.

“This unique design allows the floorplates to remain largely column-free, creating a very elegant and delicate structure,” Richard Tomlinson II, retired partner of world-renowned architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), and one of the people who worked on the campus, told the Daily Commercial News.

Another is the architectural provenance.

The building was the “precursor” to the McCormick Place exhibition center in downtown Chicago, “which is in fact slightly simplified from what was designed at Baxter,” he said.

The business park, which was incrementally added to in the 1980s, was also designed by architects who included such names as Bruce Graham and Fazlur Khan, who designed other iconic SOM buildings, Chicago’s Hancock Tower and the Willis (former Sears) Tower.

Tomlinson said the team believed in “pushing the boundaries” through innovation. When it came to the business park, this meant creating a “dynamic campus” where flexibility was the rule.

“It could expand to accommodate long-term growth or contract by subletting buildings if needed,” he said.

Besides the central facilities building, there are five office buildings of about four-to-five storeys in height and three parking garages.

The design was ahead of its time.

It took a “sustainable” approach to land utilization “uncharacteristic of its time,” Tomlinson said. “It strategically incorporated structured parking in close proximity to each office module to avoid vast expanses of surface parking and preserve its surrounding landscape.”

David Fleener, a Chicago-area architect who is testifying against the redevelopment, said the campus is ideally designed to be “repurposed for many other uses” like a community college, health centre or library.

“But to tear it down and build a windowless concrete distribution centre which in five years could be of no use, could not be repurposed for anything except a prison or an arsenal,” he said.

Baxter is not commenting on the plan.

The company wants to sell the site because it has drastically downgraded its campus workforce. The site was built to accommodate up to 2,000 people but now about 200 work there.

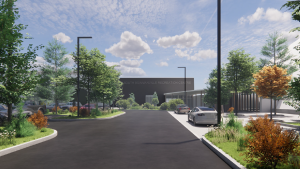

The developer is Bridge Industrial, which builds large suburban logistics terminals. The municipality of Deerfield would have to annex the more than 100-acre property first and then approve the redevelopment plan.

But not just preservationists want to save the campus.

Local residents are against redevelopment because of the host of noise and traffic issues a warehouse would cause.

“The main opposition are residential neighbors who do not want a distribution center with 600 to 1,000 trucks coming by every day up and down their streets,” Fleener, a board member of the modernist preservation group DOCOMOMO-Chicago, said.

Fleener himself worked at SOM on some of the campus’s expansion.

“We added a wing to the executive pavilion and added another garage,” he said.

Fleener said there have been hits and misses in preserving Chicagoland’s numerous mid-century office parks.

New Jersey-based Somerset Development bought the 1.6-million-square-foot former AT&T campus in 2019, with plans for a “metroburb” – a sort of all-inclusive work and living environment – which has now been partly repurposed with new commercial tenants.

“The same company has bought two or three Bell laboratory buildings in the New York area and is doing the same thing there,” Fleener said. “So it is possible to do this.”

The site was recently put on Landmarks Illinois’ 2023 Most Endangered Historic Places list.

Another campus, the Scott Foresman Headquarters in Glenview, Ill., designed by Perkins & Will in 1966, was put on the group’s 2021 list. It’s now being redeveloped into a residential neighborhood.

Ace Hardware has moved into the former McDonald’s 80-acre Oak Brook campus once the fast-food company moved to downtown Chicago.

But Allstate Insurance sold its 3.2-million-square-foot campus, also in Glenview, which was demolished.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed