As thousands of Ontarians trek up north on vacation this summer, few give thought to the enterprise, labour and ingenuity it took to carve out the roads they drive on.

Northern Ontario’s road system originated with trails and portages developed by Indigenous communities explains “Back Roads Bill” Steer, a college and university instructor based in North Bay, Ont. Some of those passages fit the terrain so perfectly they were adapted by settlers and are still in use today, he said, citing North Bay’s Ski Club Road as an example.

Steer, the general manager of the Canadian Ecology Centre, turned his passion for heritage roads and bridges into a long-running newspaper column and a CBC radio feature.

Steer’s oeuvre combines a scholar’s rigour with respect for the northern legacy and an eye for a colourful anecdote. His Back Roads features range into other heritage topics but he always returns to roadways.

“Back Roads Bill is from northern Ontario and spent a good chunk of his adult life in northern Ontario, using all those kinds of roads, whether agricultural roads, mining roads, development roads, logging roads and roads that became the transit to the Trans-Canada Highway,” said Steer.

“Because of mining and forestry and agriculture, they created the five cities of northern Ontario… all these other communities were developed by roads, so the passion comes from knowing our settlers’ history.”

One recent article documented how northern Ontario is home to not one but two Trans-Canada highways — the familiar east-west roadway numbered Highway 17 that was completed in Wawa in 1960, and the circular north-south highway that starts as Highway 11. The highways intersect twice, in North Bay and Nipigon.

Highway 11 begins at Highway 400 in Barrie, extending north from Yonge Street, and arches west through northern Ontario to the Ontario–Minnesota border at Rainy River via Thunder Bay.

The Ferguson Highway

So-called colonization (settlers’) roads opened up the north to agriculture and mining in the 19th century in parallel with railways, but the advent of the automobile kickstarted roadbuilding in earnest after the First World War.

Steer recently visited the Latchford information centre, north of Temagami, and examined a plaque commemorating the grand opening of Highway 11 North, at one time named the Ferguson highway after Howard Ferguson, premier of the province from 1923 to 1930.

The Ontario government began construction of the 420-kilometre trunk road between Cochrane and North Bay in 1925, “intended to link the rapidly developing mining and agricultural communities of ‘New Ontario’ with the province’s southern regions,” reads the plaque.

“Several sections of rebuilt local roads were incorporated into this gravel highway and the final link was completed through the dense Timagami [sic] forest. The highway was officially opened on July 2, 1927.”

In 1937 the route was extended to Hearst and then to Nipigon by 1943. In 1965, Highway 11 reached Rainy River, bringing it to its maximum length of 1,882 kilometres, Steer recounts.

In the early days, he recalled, the road was impassable for part of the year. Every spring the freeze and thaw cycle swallowed up sections and rain washed away portions of the gravel roadbed and wooden bridges.

“Stonemasons were required for permanent bridges and these permanent structures were costly to the Crown. It wasn’t until the 1950s that all of Highway 11 was paved with some form of uniformity.”

The initial road was so precarious that in the early years motorists had to register to use it. A toll booth was located north of Thibeault Hill near Cooks Mill Road north of North Bay.

The birth of the Dionne Quintuplets in Callander, south of North Bay, has been cited as spurring a new era of tourism following Highway 11, with thousands of visitors from New York and Michigan heading north to enjoy fishing and cottaging opportunities.

Roadbuilders ‘on the dole’

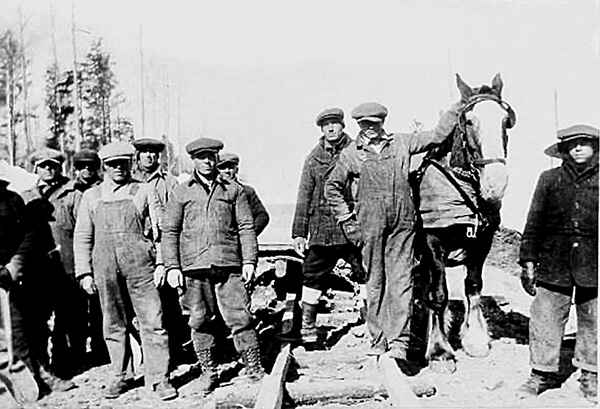

Steer and other sources such as the Ontario Archives, Digital Archives Ontario, the Toronto Public Library and the Department of Northern Development correspondence files from the era cite the Great Depression for launching another boom in northern roadbuilding when thousands of workers on relief fled to the north for work.

Men were hired to construct highways in remote areas of the province based in temporary Bennett Camps, named after then-Prime Minister R.B. Bennett.

“This provided the necessary labour to open road links through vast expanses of wilderness in a relatively short period of time,” Steer recounts.

There were 37 road construction camps throughout the province.

Despite the workers’ inexperience, the crews had “people that knew what they were doing and teamsters working steam shovels,” Steer said.

There is no evidence that the roads and bridges built were unsafe, he said, nor reports of excessive injuries despite the need for frequent dynamiting of the dense Pre-Cambrian rock.

Steer interviewed Bill Schorse of Corbeil, whose father was a clerk for the road contractor.

“One time, one of the relief workers hitched a ride back to the Calvin camp in a thunderstorm,” said Schorse. “When the stranger asked what my father was carrying in the back of the truck, dynamite at the time, the door flew open and he was gone before the next words were spoken.”

Laurel Sefton MacDowell wrote in the Canadian Historical Review in 1995 that for small northern communities like Kenora and Dryden, the work was a blessing, but single men from southern centres like Hamilton, Oshawa and Brantford, which sent 140, arrived as well.

Workers were often shamed by locals for being “on the dole,” MacDowell said, and there was concern about the camps being fertile territory for communist organizing.

The roadwork was done by horse and wagon, Steer wrote.

“After the blasting of the rock cuts, the rock mucking and transportation was done by dragging stone boats. It was the dump truck of the day.”

He recounts the aggregate used in the cement varied, and included pieces of rock, ceramic tile and brick rubble from the remains of previously demolished buildings.

“Reinforcing elements, such as steel rebar, were not used.”

The work crews dissipated by 1935.

Many people navigating the northern roadways today keep their eyes ahead or peer at a phone screen if they are passengers, Steer said — but not him.

“You see an old bridge and you wonder how old it is, and it’s mostly made of concrete and still surviving. If you’re interested, you see things on the landscape that promote questions.”

Follow the author on Twitter @DonWall_DCN

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed