The threat of a strike has historically been the ultimate leverage to compel the recognition of a trade union’s legitimacy during collective bargaining, especially in times of reduced bargaining power. But is it still the most sensible option?

Some Ontario trade unions have implemented no-strike no-lockout protocols into collective bargaining rounds, and binding final offer selection arbitration in particular, as a process they deem equal to the effect of a strike in terms of effecting recognition, but without the negative consequences inherent in a work stoppage.

In the 1980s, it seemed one or more of the trades in Ontario found themselves on strike almost every other year, each time a collective agreement expired.

While the strikes usually lasted only a matter of weeks, a dynamic emerged; non-union contractors would seize the opportunity presented by the strike, and use the labour uncertainty and forthcoming expiration of agreements as marketing promotion for themselves, threatening and arguably contributing to a slow erosion of unionized market share.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) and the Electrical Contractors Association of Ontario (ECAO), feeling this was the case, determined that they had to devise a way to gain reasonable wage increases while eliminating the destructive consequences of these recurring work stoppages.

In 1992, they introduced a no-strike no-lockout proposal that would settle disputes that occurred at the bargaining table using final offer selection arbitration (FOS). This more uncommon method of interest arbitration was approved by the membership for that round of bargaining, and has been renewed for every round since.

Currently, three Ontario building trades employ no-strike no-lockout provisions: the Carpenters Union, the IBEW, and the Painter’s Union, with the latter two opting to use FOS. The Heat and Frost Insulators Local 95 and the Master Insulators’ Association of Ontario are exploring a no-strike no-lockout protocol involving FOS, and have recently completed a joint study on the FOS process and its implementation.

Legally, the grounds for voluntary arbitration protocols including a no-strike no-lockout provision is found in Section 40 of the Labour Relations Act.

Here’s how the FOS process works:

Prior to a collective bargaining session, the negotiating parties agree on which and how many issues can be subject to FOS, and agree that they cannot use a work stoppage as a tactic to settle those issues. In the event that the parties cannot come to an agreement on one or more of those issues, they will be settled through the FOS arbitration process.

In the FOS process, the two parties take their final offers on the outstanding issue to an arbitrator, and make their arguments for their respective positions. The arbitrator then chooses one of the two final offers in its entirety. The chosen offer is binding, and included in the new collective agreement. The arbitrator has no authority to add, subtract, or construct any part of the final settlement, only to choose one offer.

In FOS, the arbitrator’s primary principle when deciding between offers is ‘replication’. Sean McGee, lawyer with Nelligan, O’Brien, Payne LLP and Counsel for the Canadian Postmasters and Assistants Association, during their final offer selection arbitration in 2010 explains, "The decision tries to replicate what would have happened had the two parties gone through the strike-lockout mechanism, and what they would have ended up with that way."

To determine what outcome would be reasonable, the arbitrator uses touchstones such as historical industry wage trends, economic factors such as the Consumer Price Index, economic conditions within the construction industry, and recent settlements in similar trades in Ontario. The relevant ‘touchstones’ can be defined by the two parties ahead of time.

FOS differs from regular interest arbitration in which the arbitrator has the ability to construct a resolution. From this ability to construct a resolution in regular interest arbitration arises one major difficulty: the ‘narcotic effect’. The perception that an arbitrator will ‘split the difference’ between the two positions can result in a dynamic expressed in the saying ‘never give up at the bargaining table what you can get in arbitration’. If a middle-ground resolution is anticipated, it’s rational for the two parties to start far apart in negotiations and remain there, attempting to make the boundaries of the agreement as extreme as possible in their favour. There is little reason to negotiate in earnest or compromise before arbitration. Why concede anything prematurely?

Furthermore, since arbitrators may account for the fact that there is an ongoing relationship between the two parties, some decisions may include sacrifices in the interest of future harmony. FOS is designed to achieve a justifiable resolution while eliminating the narcotic effect and side stepping any actions taken in bargaining that may be motivated by emotions or political concerns.

The virtue of final offer selection is that there is no middle. The process incentivizes both parties to work out the issue in question at the bargaining table. As Douglas Stanley, Arbitrator and former Deputy Minister of Labour for New Brunswick puts it, "Final offer selection is not principally a way to settle an agreement. It’s a way to incent the parties to settle their own agreement because of the uncertainty of arbitration."

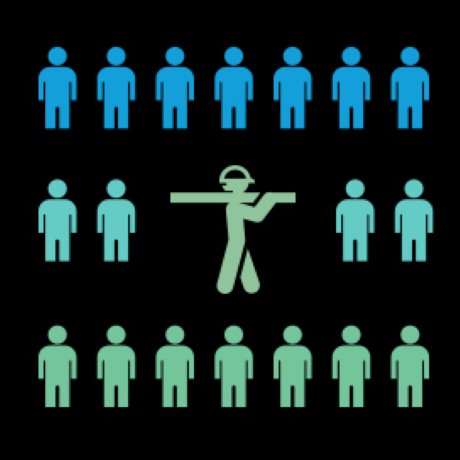

Neither side wants to totally lose control of the outcome. The threat of a strike is the traditional ‘stick’ that brings the parties together. In FOS, the uncertainty of the arbitrator’s final decision is the ‘stick’.

Lawyer Murray Clemens, with law firm Nathanson, Schachter, and Thompson in British Columbia, describes the rationale for using FOS in his paper Final Offer Arbitration: Baseball, Boxcars & Beyond: "The theory of final offer arbitration is quite simple. It was believed that the logic of the procedure itself would force the parties, even in threatened impasses, to continue moving ever closer together in search of a position that would most likely receive a neutral’s sympathy. Ultimately, so the argument went, they would come so close that despite the early threat of stalemate, they would almost inevitably find their own settlement. In short, final offer arbitration would normally obviate its own use. Even if it did not, the position of the parties would be so similar when they did go to arbitration, that the range of neutral discretion would be limited severely and thus, not threaten seriously the vital interests of either party, no matter which way the decision went."

This makes sense since, unlike with regular interest arbitration, if you put forward an unreasonable final offer before an arbitrator, you will likely lose. It’s in your best interest to provide as reasonable an offer as possible, while keeping your goals in mind. In discussion with Clemens, he further explained, "The parties realize that if their offer has a chance of being selected, it has to be within a range of reasonableness. Both parties then are driven to make their best self-interested offer within terms that will be regarded by a neutral party as reasonable. That has the effect of driving the parties together, and as supported by the evidence, results in a high number of settlements for these disputes."

The process influences the parties to make their offers as fair, fact-based, and reasonable as possible, so the theory goes.

So how has this worked in practice in the Ontario trades?

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed