There seems to be something about eggs that makes students want to protect them. In this case, it’s a $300 prize offered by the American Concrete Institute (ACI) to design and build the best impact-load-resistant plain or reinforced concrete Egg Protection Device (EPD).

The EPD competition was staged at the ACI’s recent fall 2012 convention held in Toronto. It’s one of four competitions open to students on a rotating basis, with one competition staged every six months.

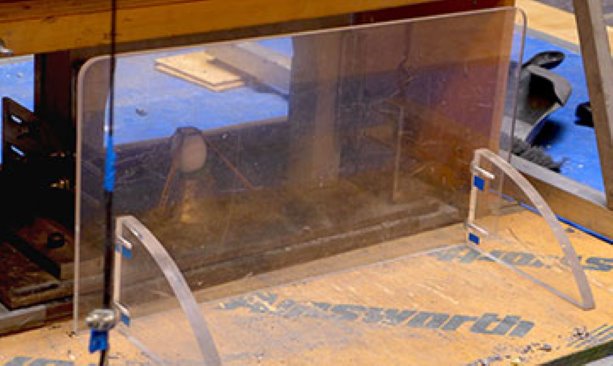

Students are required to build a concrete arch within the exacting specifications set out by the institute. Underneath the arch, a tender egg faces certain destruction by impact loading, courtesy of a 10-lb. weight from above.

The weight drops from a half-metre at first, and is then released from ever-increasing heights until it reaches three metres. The impact is considered powerful enough to shatter a construction helmet.

Walter Flood IV oversees the competition, as a representative of family-owned business Flood Testing Labs Inc. of Chicago.

“The ACI competition swung into Chicago in 2010 and that’s when I became involved with the students,” he says. “Now I’m the guy — the egg guy.”

Why an egg? “Why not,” he answers

“It’s just a way of judging the competition. The egg can start to fail and be completely cracked, but if the egg is still standing it’s still considered to be protected by the concrete arch. It’s not until the egg explodes in fragments that it’s over.”

Flood notes that the competition is subject to regular rule changes, to prevent competitors from using the same designs year after year.

“We don’t want it to become boring,” he says.

“This year, we’re applying the impact load eccentrically instead of at the centre.”

Student teams focus on mix and reinforcing design using rebar made of Number 9 wire. Some teams subject their designs to extensive structural analysis prior to the competition.

The concrete arches are initially measured by judges to ensure they qualify for competition.

“Even if they fail to qualify, we still break them,” says Flood.

“Although it would probably be a bigger punishment to send them home carrying that heavy concrete arch they worked so hard to bring here through customs.”

This year, 23 teams participated in the competition before an audience of almost 300 students. Teams represented schools in Canada, the U.S., and Puerto Rico and as far away as Mexico and Brazil.

A novel design initially drew the attention of judges, because it appeared to contravene the competition’s non-fibre rule.

“When we looked closely, we saw that these were rubber pellets used to cut the weight and qualify as recycled product on the argument that the pellets were aggregate,” says Flood.

“However, it worked as a fibre because some of the concrete pieces stuck together. So next year — rule change.”

This year’s big winner was Mexico’s Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, which took first and second place in the durability category with Texas State University nabbing third place.

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León also topped the performance category with Brazil’s Faculdade Integrada Metropolitana de Campinas taking second place honours and the New Jersey Institute of Technology securing third.

Flood notes that competitors aren’t initially aware of how the test eggs were prepared—if at all.

“Depending on who is running the competition, sometimes we’ll put soft ones in there just for fun,” he says.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed