When it comes to giant mines, there aren’t many bigger than the Giant Mine near Yellowknife in the North West Territories.

The gold mine operated from 1948 through 2004 with some 220,000 kilograms of gold extracted over its lifetime and was a major employer in the Yellowknife area.

It was a major Canadian mining icon, the site of accidents, strikes and even murder during its tumultuous history.

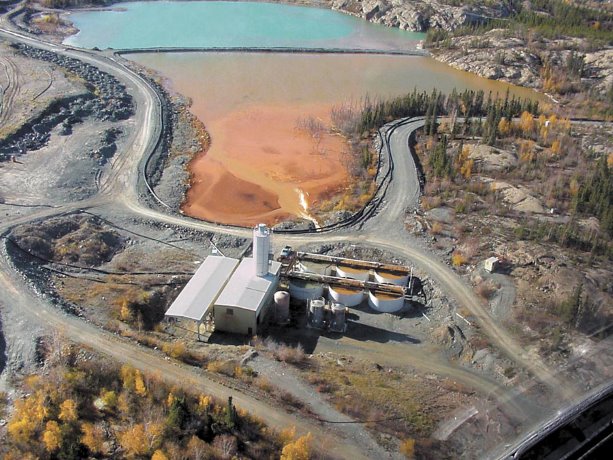

Today the mine is the subject of a giant-sized remediation project, with the $900 million plus cost borne by Canadian taxpayers because the original owners and beneficiaries of the mine have either long since faded into history or gone bankrupt. They weren’t required to create a long term plans or funding for remediation under the legislation at the time.

While plans have been in motion to secure all toxins on site and to explore options as to how best prepare and secure the 870 hectares property for future use since 2004, most has been strategic, involving community consultation and environmental assessment and discussions on what to do with the property. It may be a decade or more before the remediation project is actually completed, said deputy director of remediation Natalie Plato.

Thus far the process has been one of narrowing down options, including whittling down 56 management alternatives to one.

The biggest challenge off the top is how best to secure 237,000 tonnes of arsenic trioxide left behind in underground chambers.

"We are looking at cryo-technology, the frozen block method, to freeze the arsenic in place," said Plato. "This is a common practice and of course during the winter we have lots of cold air up here."

The arsenic would remain in the underground chambers, 100 feet below the surface where the ambient temperature is constant. Freezing would prevent the toxins from leaching in the event of flooding which is a big concern locally given the proximity to Baker Creek and Yellowknife Bay.

It’s an extension of the original storage method which leveraged the natural permafrost to seal in the arsenic trioxide — a byproduct of extracting gold from arsenopyrite ore. The ore was roasted to release the goal and arsenic gas was formed and captured to cool as arsenic trioxide.

There is additional surface contamination of arsenic trioxide and asbestos around the roasting buildings on the surface. Work has been ongoing to decontaminate the structures and ultimately tear them down.

Other work includes an $11.6 million interim underground stabilization contract to excavate, relocate, and process tailings into a paste by mixing them with water and a small amount of cement. This paste will be pumped underground to stabilize some of the mine’s stopes — underground voids created during the mining process.

The plan is to freeze 15 underground chambers and stopes to create an impenetrable barrier and prevent water from entering or leaving.

The technology uses a combination of active and passive freezing systems. The first active phase circulates cooled liquid through a series of underground pipes to freeze the area around the chambers and stopes.

The second passive phase then maintains the temperature using thermosiphons, tall, metal tubular devices which take the heat out of the ground and exchange it into the air using pressurized carbon dioxide.

It works on the principle of thermos-expansion. The CO2 is a liquid within a loop. When one part of the loop has a temperature differential that fluid is more buoyant. It rises to the top where it cools and then falls again, creating circulation.

The physics involved mean thermosiphons don’t need external power and are a common technology in the N.W.T., even at it provincial legislature, for example, to maintain the permafrost in the parking lot for geo-stability and to maintain frozen core dams at the BHP Ekati Diamond Mine. It’s also highly cost efficient and not moving the arsenic trioxide means there’s no risk of a spillage and secondary contamination.

The site and project are being managed by a partnership of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and the Government of Northwest Territories along with the Deton’Cho Nuna Joint Venture.

Public Works and Government Services Canada are contributing project management, engineering, procurement, and environmental services.

It’s been a long journey with many more steps to go.

"The environmental assessment in 2014 noted 26 requirements and we’re now working towards addressing all of those," said Plato.

The next challenge will be to determine what to do with the open pit. Local stakeholders, which include FN and the City of Yellowknife along with other northern organizations, have expressed a clear preference for filling in the hole.

The question is then, with what?

"We are looking at tailings," said Plato noting tests have to be done to determine what levels of toxins might be in the tailing and at what levels and if they can be filtered out if required.

"Then the question is how to cover it, which is either putting a grey stone cap on it or covering it with vegetation," she said.

The mine held an industry day information session last winter and hope to tender for a main construction manager in the near future.

Final usage for the remediated site haven’t been confirmed yet but there are plans from the community to build Northern Canada’s first mining museum.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed