The prospect of slower growth and, quite possibly, a recession, will probably reduce the demand for labour and temporarily lower Canada’s job vacancy rate in the near term. However, if you think there’s a shortage of workers now, just wait a couple of years – the problem is going to get worse.

A recent analysis by Statistics Canada reports that the nation’s population aged 55-64 increased by 308,000 between 2015 and 2021, to an all-time high of 5.2 million. Over the same period, the number of individuals 15 to 24, the age when most young persons enter the labour force, declined by an estimated 53,000, to settle at 4.3 million, a 15-year low. Going forward, based on Statistics Canada’s projections, although the number of entrants into the labour force will move gradually higher over the next ten years, they are likely to be significantly outnumbered by a more rapid rise of retirees aged 55-64.

Two ways to boost the labour force

The key factors which could help offset the slowdown in labour force growth are increased net migration and increased labour force participation. However, according to Stats Canada’s analysis “an increase in immigration, – even a large one – would not significantly curb” the projected shrinkage in the relative size of the working-age population. Stats Canada did note, however, that “a higher labour force participation rate among persons 50 and older could play a role in reducing the impact (of a shrinking inflow of younger workers) on the labour force”.

Seniors can work longer due to changing nature of work and increased longevity

The prospect for an increase in labour force participation among individuals 50 and over is reinforced by the fact that Canadians are living much longer due to improvements in diet, advances in medicine and healthier lifestyles. Also, as noted in a recent Fraser Institute paper titled Barriers to the labour force participation of older workers in Canada, there has been a relative increase in employment in the less physically taxing service sector, together with an accelerated rise of automation in goods production.

Fuelled by the pandemic, working from home, which appeals more to older workers than to younger ones, has risen steadily over the past two years. Other factors that will likely motivate more older workers to remain in the workforce is the recent sharp rise in headline inflation and the related steep drop in equity prices.

Since 1976, the life expectancy of the average Canadian has increased by almost a decade, from 72.5 years to 82 years. Despite a brief interruption in 2020 due to a surge of Covid-19-related resignations, the percentage of individuals over 65 in the labour force rose from 13.8%, on average, in 2020 to 14.0% in 2021. The 14.0% was just slightly below the record high of 14.6% reached in 2019.

Financial disincentives and other barriers encourage retirement at 65

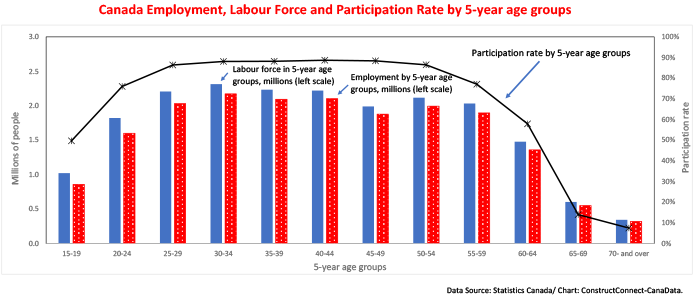

There is no such thing as mandatory retirement in Canada and, as noted above, individuals are living longer, and the nature of work has become more elderly friendly. However, the sharp drop in the participation rate (see chart) from 58% for 60-to-64-year-olds to 14% for those over 65 suggests there are significant, and in many cases unintended, barriers which are encouraging individuals to withdraw from the labour force when they reach 65.

Among such barriers is age discrimination which is perhaps treated with more leniency by human rights commissions than are cases involving race, sex, or disability. Other obstacles which encourage those over 65 to leave the workforce relate to government and private sector pension plans, as well as individual retirement savings plans. In many cases, the benefits of these plans are reduced if the recipient earns income from the labour market. As a result, older individuals who wish to remain in the workforce are “progressively” penalized for doing so.

Government Inaction

In 2015, Ottawa’s current administration reversed the previous government’s 2012 plan to increase the age of eligibility for Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement from age 65 to 67 by 2029. As a result, Canada is not following the lead of 16 of the 22 high-income countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development which have raised, or are planning to raise, the age of pension eligibility above 65 years.

Given this policy inaction and the looming record increase in individuals aged 65 and over in Canada, it appears the barriers to the participation of seniors in the labour force will persist, causing the nation to continue to face a prolonged period of skills shortage in accommodation and food services, administration, construction, and professional services.

John Clinkard has over 35 years’ experience as an economist in international, national and regional research and analysis with leading financial institutions and media outlets in Canada.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed