It’s been a busy few years at the Ashbridges Bay Treatment Plant (ABTP) where the outfall is being upgraded to better handle storm surges and population growth demands, but the end is in sight.

The ABTP is the second largest plant of its kind in Canada and one of the oldest, dating back to 1917 with the outfall constructed in 1947. It is one of Toronto’s four water treatment plants.

The scope of the work is complex and extensive, adding a new outflow pipe to take discharge further into Lake Ontario after treatment by a new ultra-violet sanitization system.

As such the plant does not use chemical sanitation.

The scope includes a new integrated pumping station to move more raw sewage wastewater to the plant.

Additionally, there is other work and other upgrading pump stations and water flow diversions as part of the $3 Billion Don River and Central Waterfront Wet Weather Flow System and Connected Projects.

The city says the plant upgrades are within budget, though there have been some challenges with COVID-19 and site surprises.

The projects are a 25-year program to boost water quality in Toronto’s Lower Don River, Taylor-Massey Creek, and Inner Harbour.

Frank Quarisa, director of wastewater treatment with Toronto Water, says the project is roughly 80 per cent complete with a completion date now planned for summer 2024, just under a year past the original schedule of 2023.

“Structural is 85 per cent complete, mechanical is 70 per cent and electrical is 85 per cent complete,” he said. “Then, instrumentation and controls are 70 per cent complete.”

The rest of the project schedules are falling into place with the bypass conduits nearing completion, he added, and effluent conduits are also almost finished.

Meanwhile, Quarisa says, the UV/Chemical building is up and enclosed with some 90 per cent of the major UV/Chemical equipment delivered and in a location pending electrical, mechanical, instrumentation and control work completion.

“The plant water pump station, seawall substation equipment is installed and commissioned,” he says. “The commissioning and testing of UV/chemical systems is the next major activity.”

Also, he says commissioning for Phase 2, the UV Disinfection Building, is scheduled for fall this year into early summer next year.

The UV system is being installed by Graham Construction as part of a $236.5-million contract for a first-of-its-kind in Toronto system being supplied by Trojan Technologies of London, Ont.

While the system was projected to cost at least $66 million more than a chlorination system and $440,000 more in operational costs annually, it’s considered state-of-the-art and can disinfect a peak flow of 2,000 million litres per day.

As always with projects this size, there have been challenges, says Quarisa.

“The contractor encountered some concrete, materials and electrical equipment supply issues,” he says. “Work involving Toronto Hydro and other electrical authorities required extensive co-ordination with the contractor, the consultant and the city. Also, co-ordinating plant shutdowns for the testing of new systems is challenging as plant operations must be maintained throughout all testing. Frequent communication within the project team and with other key parties is the takeaway lesson, as well as flagging any potential issues as soon as identified.”

That’s borne out by the multitude of agencies involved in permitting and approvals, creating something of a communications challenge: Aquatic Habitat Toronto, Toronto Region and Conservation Authority, Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, Transport Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard, and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

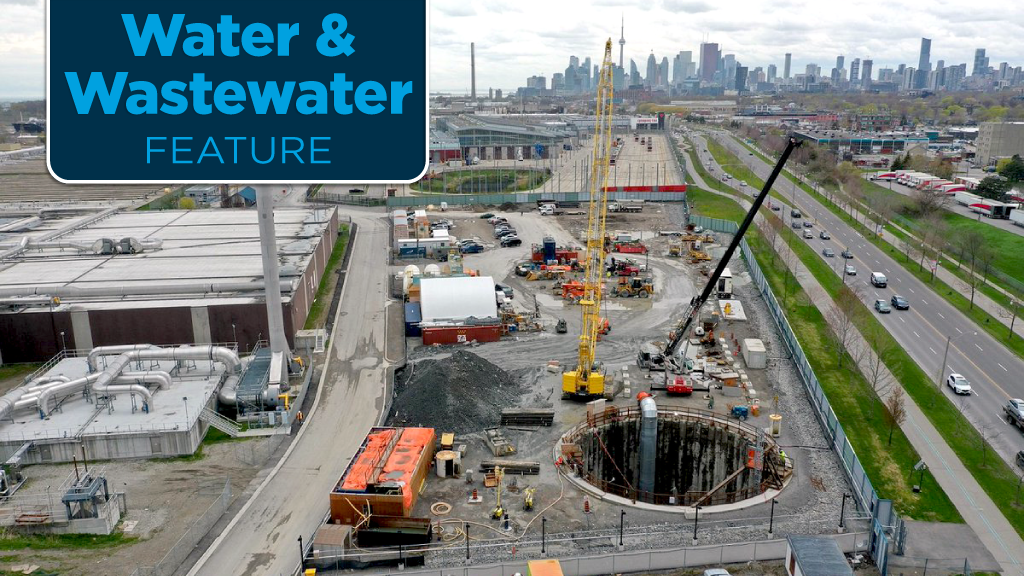

Almost all of the work is hidden from the public eye, as it’s perched on the shore of Lake Ontario just a few kilometres from downtown Toronto and adjacent to the popular recreational beaches and boardwalks of the Beach neighbourhood by the Leslie Street Spit.

It has been a complex set of engineering challenges involving a 14-metre-diameter shaft sunk down some 85 metres deep to allow the tunnel boring machine access to create a 3.5-kilometre-long, seven-metre tunnel though bedrock underneath Lake Ontario.

The tunnel in turn serves as a conduit for the outflow pipe which discharges processed water through 50 riser pipes coming from the last kilometre of the pipe, through the lakebed into the water.

Those riser pipes were drilled through the lakebed from barges and connected once the main outfall was in place. The main pipe is angled downward so the discharge flows with gravity.

The design is intended to disperse the discharge so that there’s no single point of collection for phosphorous concentrations.

Recent Comments