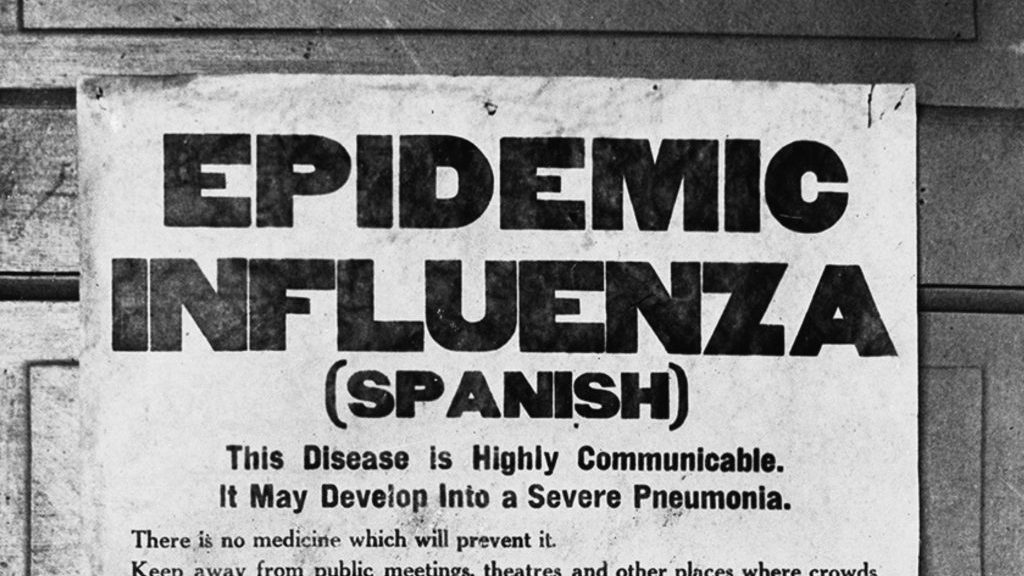

The outbreak of COVID-19 brings to mind Canada’s experience with the Spanish Flu, a lethal influenza pandemic that affected the whole world.

Between January 1918 and December 1920, it infected 500 million people, about one-quarter of the world’s population at the time.

Anywhere from 17 to 50 million, and possibly as many as 100 million, succumbed to the disease.

In Canada, it killed 55,000 people out of a population of eight million. No part of Canada was immune. In Winnipeg, Man., population 180,000, 1,200 people died.

The Spanish Flu in Winnipeg was sandwiched between two major labour disruptions. All three had in common that they contributed to already tense class and ethnic relations that remained unfriendly until well after the Second World War.

The disease struck in the fourth year of the First World War, a difficult time for the city’s construction workers and their extended blue-collar family. Low, subsistence wages combined with high prices to create an inadequate and declining standard of living.

The situation was especially dire for common construction labourers, who worked a 60-hour week for 30 cents per hour. In the building trades, the highest paid workers were stone carvers, who earned 87-and-a-half cents an hour for a 44-hour week.

In April 1918, Winnipeg civic employees began negotiating with the city on wages. Talks were unsuccessful, and in early May electrical workers voted to go on strike. The situation gradually escalated until mid-May when freight handlers and freight checkers went out. This immediately got the federal government’s attention; the war effort depended on Canada’s railway system performing at peak efficiency.

Ottawa told city council to accede to the strikers’ demands. Both sides came to an agreement, the strike was called off and a final settlement was signed in July. Opinions for and against the strike and the settlement were polarized, a sign of things to come in 1919.

The strike had barely been settled when the Spanish Influenza hit Winnipeg. The pandemic arrived at a time when the city was experiencing serious social and economic tensions caused by its rapid but uneven growth.

Winnipeg’s civic and economic affairs were dominated by an Anglo Protestant elite that kept a firm, unyielding hand on the levers of power. The city’s establishment expected the city’s working class, which included many poor Slavs and Jews crowded into the north end, to do what it was told, when it was told.

The Spanish Flu touched many families in Winnipeg, but not all in the same way. Because they had relatively few options for fighting the disease, the city’s working class and ethnic population suffered disproportionately more illnesses and deaths. Many working-class sick avoided the city’s hospitals, fearing they or their families, should they die, would face hefty bills.

The cost of funerals during the Spanish Flu rose precipitously, which prevented many working-class families from giving their loved ones a decent burial.

And the city’s establishment, despite its fears that the unchecked spread of influenza in blue-collar neighbourhoods was a threat to social stability, excluded organized labour from contributing to disease control and management.

The Spanish Flu ran riot in the city between September 1918 and January 1919.

In early May 1919, what became known as the Winnipeg General Strike began when the city’s building trades and metal trades downed tools after failing to get contracts with their employers.

Members of the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council voted for a general strike. They were joined by others who walked off their jobs in a sympathy strike. Soon 25,000 to 30,000 union and non-union workers were on strike. As the work stoppage wore on, many business and government people worried it was more than just a labour dispute.

Were Bolshevik revolutionaries planning to take over Winnipeg, like Russia in 1917?

Local businessmen formed the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand and encouraged employers to resist the strikers’ demands. They also tried to stir up resentment of “alien” immigrants from Europe, who, they said, were the strike’s instigators and leaders.

The climax of the strike came on June 21, “Bloody Saturday,” when Mounties fired on the demonstrators, resulting in numerous casualties and two deaths. On June 26, the strike was called off and workers began drifting back to their jobs.

The Spanish Flu hit Winnipeg at a tumultuous time in the city’s history. In the rest of the world, it coincided with many other calamities: in the U.S., race riots, the revival of the Ku Klux Klan and the post-war Red Scare; in Germany, a civil war; and in Italy, the rise of fascism.

The whole world was living in interesting times indeed.

The author acknowledges his debt to accounts of the Spanish Flu and the strikes of 1918 and 1919 in the following:

1. Influenza 1918/Disease, Death and Struggle in Winnipeg, by Esylit Jones (Book)

2. The Strike in Winnipeg in May 1918. The Prelude to 1919?, by Ernest Johnson (MA thesis).

3. “Spanish” Influenza Visits Winnipeg (West End Dumplings Blog)

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed