The swinging of a wrecking ball demolishing an old building once signalled the rise of new and better things. Over the past decade, the trend has shifted away from complete demolition towards preserving and reusing the materials in the original structure.

It’s called deconstruction, a term now familiar whenever new projects on existing sites are discussed. A concise definition of deconstruction is “construction in reverse,” the selective dismantlement of building components, specifically for reuse, recycling and waste management.

“When I first started dealing with these issues, less than 10 per cent of the construction materials had the potential to be recycled; today it’s more than 60 or even 70 per cent,” Mauro Spagnolo, editor of Italian web magazine Rinnovabili.it, told Household. “So, technology is progressing.”

He sees this as a cultural transformation that will revolutionize the building industry.

If that revolution is to occur, it will be the result of individual municipalities stepping up and developing deconstruction criteria suited to their situations.

Although guidance from higher levels of governments would be helpful in advancing deconstruction, it is individual cities and towns which control most building and demolition permitting.

Deconstruction’s most significant progress can be seen in Europe, home to several examples of new projects created from deconstructed materials.

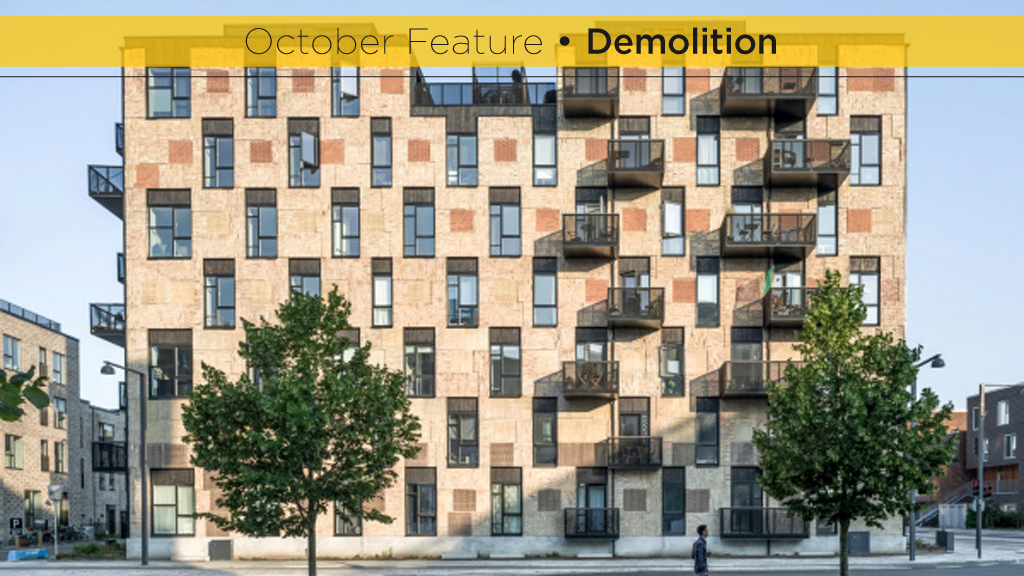

In Copenhagen, a new housing development called Resource Rows reduced its carbon impact by as much as 60 per cent by reusing material from a former Carlsberg brewery, including sections of brick cut and made into a patchwork of exterior panels. Project architect Anders Lendager says 463 tonnes of material waste was made useful.

The 2019 World Building of the Year award was given to the transformation of a train shed built in the 1930s in the city of Tilburg, Netherlands, into a new public library and learning centre. Much of the original form was preserved, minimizing the amount of new materials while giving the final design a raw, open and contemporary look.

The City of London has published guidelines requiring large construction projects to complete both whole-lifecycle carbon assessments and circular economy statements. These must demonstrate the reduction of new material demands in the project, while also accounting for building materials, components and products to be disassembled and reused at the end of their useful life.

The shift towards mandated deconstruction is finding its way to North America, starting with homebuilding.

Backed by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Partnership for Advanced Technology in Housing is a public-private effort to develop “the next generation of American housing.” Its Guide to Deconstruction is seen as an innovation tool advancing this new approach to redevelopment.

Portland, Oregon adopted a deconstruction ordinance in 2016 that requires residential homes built in 1940 or earlier be “deconstructed” rather than demolished. The list of cities with similar ordinances now includes Milwaukee, San Antonio, the cities of Palo Alto and San José in California, and several more.

Canadian municipalities on Canada’s West Coast have come up with their own versions of deconstruction mandates.

Burnaby, B.C., charges a deposit capped at $50,000 for the demolition of buildings larger than 22,000 square feet. The deposit is refunded if a compliance report, complete with receipts from recycling facilities, establishes that at least 70 per cent of the material was recycled. It’s not exactly the same as deconstruction, but it’s an effort.

Port Moody sets higher levels for recycling; 100 per cent for clean uncontaminated wood and at least 85 per cent for everything else.

Although ordinances are not currently in place in Toronto, deconstruction is a growing trend. For example, a former abattoir in the city centre will be replaced by a million square feet of new apartments across five buildings.

The original red brick made in the Don Valley more than 100 years ago, along with portions of the concrete foundation, will form retaining walls. Steel chimneys will be transformed into planters.

Time and labour are challenges to deconstruction. Going forward, experts believe the key will be designing buildings for eventual disassembly. Much discussed is the concept of “material passports,” a digital database of all materials going into a building at its creation, allowing the future use of those materials to be easily determined.

Steel is a strong candidate for this approach. Some analysis suggests 70 per cent of the energy and 80 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions could be reduced using as-is steel components versus melting the material for recycling and reforming.

Leonora Eberhardt of Danish civil engineering firm Cowi, told the BBC she hopes the built environment will become an asset to be shepherded and passed down to future generations, rather than a physical asset to be owned today.

That vision can be realized if more individual municipalities embrace and mandate the concept of deconstruction.

Recent Comments