Strong, fireproof, soundproof and an excellent insulator against heat and electrical current — at the end of the 19th century, asbestos had all the makings of a miracle construction material. By the beginning of the 21st, its reputation had fallen to that of a carcinogen and toxic substance.

Cancer research group CAREX Canada estimates that approximately 152,000 Canadians are exposed to asbestos in the workplace. The largest industrial groups exposed are specialty trade contractors, followed by building construction workers who may have been exposed to as many as 3,000 building products containing asbestos. Asbestos exposure, primarily the inhalation of fibres, can cause: asbestosis and pleural thickening, diseases related to the scarring of lung tissue; lung cancer; and mesothelioma, a cancer of the tissues lining internal organs.

Research funded by the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute estimates that asbestos exposure currently causes 1,708 work-related lung cancers and 391 mesotheliomas each year.

Use of asbestos preceded the industrial age. Asbestos fibres were employed for uses as diverse as candle wicks, shrouds for funeral pyres and cookware crafted by indigenous people.

Dr. Jessica van Horssen, a professor at Leeds Beckett University in the U.K. is a leading researcher on the history and impact of asbestos in Canada. Her book, A Town Called Asbestos, recounts the story of Asbestos, Que. and the nearby open-pit Jeffrey Mine, the largest chrysotile asbestos mine in the world.

"Asbestos really didn’t catch on for mass use until the First World War, when electricity started to be incorporated in urban homes and buildings," she says. "Electricity was a very dangerous new technology that often resulted in great fires sweeping major urban centres. Asbestos can withstand heat of up to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The mineral was suddenly an essential inclusion in home insulation, electrical wire coverings and materials used to prevent buildings from burning down."

Asbestos materials were also heavily incorporated into reconstruction efforts in Europe following the First World War to prevent urban fire damage from future wars.

"Canada’s asbestos industry boomed in the interwar period," she says. "The western world couldn’t get enough of asbestos, and new applications for it were developed constantly, including use in brake pad linings and cement, to make them more durable."

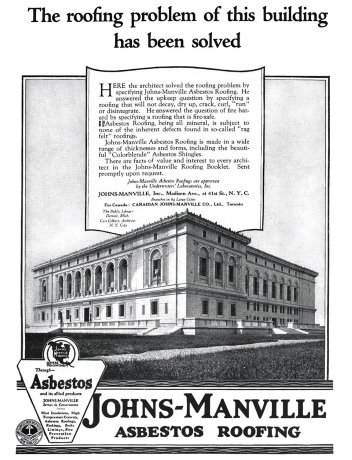

One of the largest asbestos-producing companies in the 20th century was U.S.-based Johns-Manville Co. (JM), which owned and operated the Jeffrey Mine in Asbestos, Que. Most of the company’s asbestos-based products were initially aimed at the construction industry.

"Construction workers were among the first to be exposed to processed asbestos-based goods," says van Horssen. "As a construction material company, JM was key in developing these goods — they knew the market, and knew where fireproof materials were needed."

The range of asbestos–containing construction products eventually included pipe coverings, wire coverings, insulation, fireproof boards, floor tiles, ceiling tiles, roofing shingles, and asbestos cement, asphalt, paint and plaster.

Like so many industrial diseases, knowledge of those associated with exposure to asbestos advanced slowly.

Nellie Kershaw, a textile worker for Turner Brothers Asbestos in England, died of asbestosis in 1923, leading to the discovery of the disease. Her family was the first to receive compensation for her asbestos-caused death. However, while Canada supplied much of Britain’s asbestos, so did African suppliers.

"The African asbestos was blue, compared to Canada’s white," says van Horssen. "The Canadian industry, led by JM, stated that Kershaw died due to blue asbestos exposure, not white. Turner Brothers officials privately denied that this was true, but the Canadian industry was suddenly marketed as the ‘safe’ type of asbestos. Multiple generations of miners in Canada mistakenly believed they were not at risk."

However, in coming decades, rising evidence indicated that not only miners and factory workers, but also end users, including construction workers, were being affected. Asbestos lobby groups and industry stakeholders, on the other hand, continued to insist that the product could be used safely.

The Royal Commission on Matters of Health and Safety Arising from the Use of Asbestos in Ontario was published in 1984 and proved pivotal. The report promoted a ban on the use of crocidolite and amosite asbestos, but said that the chrysotile variety could be used with appropriate dust controls.

"The report radically raised the profile of workplace risk and worker safety, including those in the construction industry," says van Horssen.

Still, the production of asbestos and use of asbestos products continued and progress on the occupational health and safety front moved slowly. Even as more countries banned the product, new markets were sought for Canadian asbestos in countries with less stringent health and safety laws.

By 2012, Quebec remained the last Canadian jurisdiction to promote asbestos mining. A Parti Québécois election victory that year saw a promised provincial loan to re-open the Jeffrey mine cancelled, ending asbestos mining in Canada.

In 2015, Saskatchewan launched an online registry of public buildings containing asbestos. In 2016, Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) created The National Asbestos Inventory, listing all buildings it owns or leases and indicating whether or not they contain asbestos materials. It also banned the use of asbestos-containing materials in all PSPC projects.

While asbestos-containing products, including construction materials, continue to be imported into Canada, the federal government promises a ban on the manufacture, use, import and export of asbestos under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act in 2018.

However, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control estimates that it may take 40 years or more for the effects of asbestos exposure to manifest itself. In many jurisdictions, asbestos-related illnesses continue to trend upward as older people succumb to earlier exposure and authorities improve efforts to accurately track asbestos-related illnesses in retired workers.

"Our organization is calling for better monitoring and surveillance of people who may have been exposed to asbestos at some point in their lives, as well as building up resources to support those people if they develop health issues," says Fe de Leon, researcher at the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA).

While the Saskatchewan and PSPC databases represent good first steps, CELA says it would like to see such registries expanded.

"Having a federal database would be much better than having individual databases in each jurisdiction," says De Leon.

"That may be challenging considering the division of federal and provincial authority on certain issues, but we believe the federal government should take leadership to develop that registry. Ideally it would cover academic buildings at all levels, industrial facilities, institutional buildings and residential buildings, such social housing. A registry such as this would not only protect workers but people using, working or living in those buildings."

Travis Robertson is a regional safety advisor with the BC Construction Safety Alliance (BCCSA), which represents 41,000 employers in the province. He notes that legacy asbestos remains a significant problem both in B.C. and across Canada. The overheated real estate market in the Vancouver area has seen significant demolition and renovation of existing building stock, often exposing building materials containing asbestos.

"A lot of contractors think that they’ll only find asbestos in buildings from the 1970s and 1980s or earlier," he says. "But it also affects much newer buildings. We had reports from one of our member contractors who has a blanket policy on asbestos testing in each project. Samples from a building constructed in 2008 tested positive."

He notes that contractors now face few barriers to understanding the hazards of asbestos. The cost of testing air and material samples has continued to decline, with lab results often available in a just a few hours. Organizations such as WorkSafeBC continue to provide educational materials, while getting tough on enforcing regulations involving contaminated work sites.

"BCCSA offers free expertise to contractors on any safety issue, including asbestos," says Robertson. "Through our mentorship program we can help to review their safety program, help to amend their safe work practices or help them to update their exposure control program. A new generation of younger workers is much better informed about the hazards presented by asbestos. Hopefully they’ll see future asbestos-related disease numbers trending downward."

1/4

This photo shows what anthopyllite asbestos fibres look like under a scanning electronic microscope.

Photo: UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

2/4

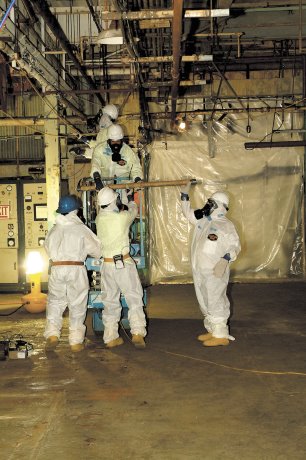

Workers remove asbestos from a building slated for demolition. Legacy asbestos in buildings continues to pose a health threat to Canadian construction workers.

Photo: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

3/4

An asbestos miner at the Thetford Mines in Quebec.

Photo: LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

4/4

A Vintage JM ad.

Photo: PUBLIC DOMAIN"

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed