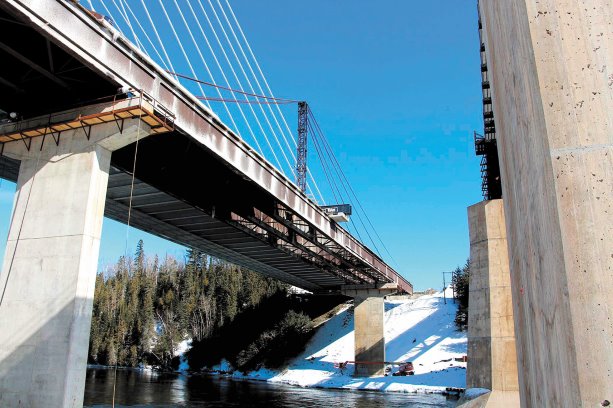

Once the first span of the new Nipigon Bridge in Nipigon, Ont. was ready to accept traffic, its 51-year-old predecessor was slated for removal. Instead of demolishing the bridge over the Nipigon River, engineers offered a more efficient option — rolling the bridge across its piers and then gradually dismantling it on shore.

Western Mechanical Electrical Millwright Services Ltd. provided the demolition design as a sub-contractor to Priestly Demolition Inc.

"The bridge is over 800 feet long, with a 270-foot span over top of the Nipigon River," says Mark Carney, senior engineer with Western Mechanical.

"That’s a particularly long span over a particularly fast current, so it would have been difficult to go in with a more traditional approach using barges outfitted with cranes. It would also be preferable to avoid potential environmental impact and the mitigation measures we would have to put into place that would result from dismantling a bridge across a waterway."

The engineering firm had originally looked at the possibility of lifting the bridge deck using strand jacks, then gently lowering it to a few feet above the river. The bridge could then be deconstructed using conventional cranes parked on shore.

"However, that would have involved a lot of costs in crane work and specialty equipment," says Carney.

"We decided that it would be more economical to roll the bridge off its supports, which would also be better from the perspective of both occupational health and safety and environmental regulations."

Western Mechanical built catwalks and support infrastructure around the bridge in the summer of 2015. However, the demolition phase was delayed until the end of February, following the temporary closure and repair of the new cable-stayed Nipigon Bridge, which had experienced a problem with its bearing hold-down system.

"We manufactured 48 custom-built rollers to support the five-million-lb. bridge," says Carney.

"In many cases a heavy load like this is moved by external power, such as a strand jack, or it’s pushed or pulled by an excavator. For this project, every fourth roller was hydraulically powered and the entire set of rollers was patched into a computer-controlled hydraulic circuit. The rollers were also on rockers so even if there was some deflection as the bridge was moved, there would still be contact."

Guides placed alongside the bridge ensured that the deck would continue to move in a straight line. The guides were regularly monitored and adjusted by crew members. Strand jacks raised the nose of the bridge where it came off the rollers, negating any severe deflection that might have shocked the bridge and risked collapse.

"The beauty of the whole system was that it was a deconstruction assembly line," says Brian Priestly, operations manager, with Priestly Demolition.

"As the nose moved onto shore, we had an excavator outfitted with a chisel hammer punching out the concrete of the deck as it was rolled off its bearing plates and piers. As the bridge moved forward, the excavator moved backward and continued to chisel away."

As the bridge passed the abutment, only steel girders were left. These were cut apart using torches and excavators outfitted with shears.

"We did one span of the four-span bridge each day," says Carney. "By the time we were finished we had a neat heap of concrete 70 feet in diameter and the steel was being moved off site. Before the bridge was fully delaunched, Priestly was already jack-hammering the remaining concrete piers, which were all on land."

Construction of a second cable-stayed span is slated to begin on the site of the demolished bridge.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed