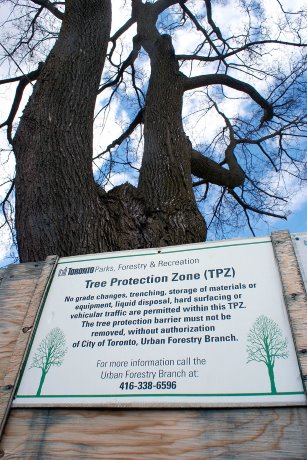

If tree protection zones (TPZs) built by construction companies appear to be getting larger, it isn’t because the regulations have changed — it’s because building contractors are becoming more savvy about what’s required to meet those regulations.

"Since the Private Tree By-law was passed and became law for the entire city of Toronto in 2004, there are a lot more people who are better educated," says Tara Bobie, acting supervisor of tree protection and plan review, North District, with City of Toronto Urban Forestry. "A lot of builders do multiple projects inside the city and they understand that one of the best ways to navigate our process is to come to us with plans and proposals where there’s any doubt."

Initial ideas about the bylaw and tree health may have led to early misperceptions that a TPZ was required to protect the trunk of the tree from being harmed. That resulted in barriers being built closely around the trunk. While trunk protection is important, the TPZ is also designed to protect the extent of roots radiating from the trunk below the soil.

"It’s easy to illustrate the damage caused by an excavator that’s slammed into the trunk of a tree, or an excavation where roots have been severed," says Bobie. "It’s more of a struggle to illustrate how driving vehicles across the TPZ or piling debris, equipment or backfill on the surface compacts the soil and damages the roots. In many cases, you can’t see the damage to the tree caused by soil compaction until months or years later. In most cases, damage to a tree or its roots can’t be reversed."

The extent of a TPZ required during construction is primarily a function of the diameter of the trunk. For example, a trunk diameter of 10 to 30 centimetres requires a TPZ of 3.6 metres from the trunk base, while a diameter of 91 to 100 centimetres requires a circumference of 12 metres. However, a larger TPZ may be required based on the drip line of the tree — the maximum circumference of the tree, measured by the extent of its branches.

The bylaw describes the type of barrier required, typically a plywood hoarding 2.4 metres high, or orange plastic web snow fencing where visibility is important.

"In some cases, where constructing a traditional vertical tree barrier isn’t possible, a project can hire an arborist or landscape architect to create a horizontal barrier," says Bobie. "This involves placing layers of mulch or loose material over the ground, and then placing plywood boards on top of that to distribute the weight and prevent soil compaction."

Bobie says that Toronto Urban Forestry will inspect certain sites, but in general, bylaw contraventions are reported to the office.

"Our department does a good job of protecting the city’s trees, but we typically can’t visit every construction site with a TPZ," she says. "In most cases we’re alerted to potential violations by neighbours and private citizens who feel that something is not right and that prompts us to send someone out to the site."

Typically, default responsibility for a tree protection plan lies with the project owner. Toronto Urban Forestry can issue orders to comply and stop-work orders if the bylaw is being contravened. Following city council approval in December 2015, the department can now also recover the costs associated with bylaw contravention inspections from project owners.

"This year, we’ve been using those tools in a more broadly consistent way," says Bobie. "This has allowed us to be more efficient in directing site clean-up and mitigating tree damage."

Those convicted of an offence under the bylaws can pay a steep price — anywhere from $500 to $100,000 per tree. A "special fine" of $100,000 can be added to the total.

"However, handing out fines doesn’t help tree health and it isn’t our preferred course of action," Bobie says.

"The purpose of the bylaw is to protect trees, not to stop construction. Hire a really good arborist to create a tree protection plan and there’s no reason why healthy trees can’t co-exist with a construction project."

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed