Fifty years ago as Canada celebrated 100 years as a nation, the centrepiece spectacle was Montreal’s Expo 67, a project that filled Canadians with pride and elicited a six-month outpouring of sunny nationalism unlike anything before or since.

Expo 67 has been called the best world’s fair ever. The New York Times praised its "sophisticated standard of excellence…(that) almost defies description." Author Pierre Berton said it was a miracle. How, he asked, did we manage to pull off the greatest world exposition in history with about half the start-up time that most of the world’s fairs require?

"The cult of extravagance, which was the hallmark of the period, reached a kind of peak at Expo," wrote Berton in his book 1967: The Last Good Year. "Expo was an architectural three-ring circus in which designers indulged themselves with every conceivable shape, size, texture and colour."

Canadians and Americans — especially New Yorkers — attended by the millions, and the final visitor total of 55 million was more than double projections.

As a construction project, the spotlights were on the project managers with the Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World Exhibition, on architects from around the world who were summoned to design some 850 buildings on the Expo site, and on municipal politicians, planners and engineers tasked with preparing urban infrastructure in the Montreal area that would ready the region to greet the world.

Royal Architectural Institute of Canada president Ewa Bieniecka, a Montrealer, visited frequently with her parents as a young girl. The experience contributed to her choosing her career as an architect, she said.

"The skyline was different," she recalled. "There were no cars, there were crowds, everyone was walking, and there were these pavilions. Every single one had a different appreciation from the outside, every one was a discovery. I have no pictures, but it’s something I’ve lived, and it marked me.

"Whether it was seeing light filtering through a tent at the German pavilion, or the Czech pavilion, with its crystals on display, it was innovative."

Amazingly for a project of its complexity, Expo was built in just four years.

After the Soviet Union backed out of its commitment to the Bureau International des Expositions to host a fair in 1967, Canada applied to take its place, with the Diefenbaker government giving the go-ahead in November 1962. The Liberals under Lester Pearson were elected the next spring and a thinkers club was convened in Montebello, Que. with such intellectuals as Hugh McLennan and Gabrielle Roy asked to develop a possible vision for the exposition.

The theme that emerged, Man and His World, based on the 1939 memoir by humanist philosopher Antoine de Saint-Exupery, would guide architects in the design of pavilions. As explained by York University PhD candidate David Leonard, a frequent speaker and writer on world’s fairs, Saint-Exupery suggested that by carrying one stone one can contribute to the building of the world.

Philosophy aside, for constructors there was earth to move. Pushing the pace on the municipal infrastructure side, Berton wrote, was Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau, who supported the St. Lawrence River site and the expansion of a piece of land in the Hochelaga Archipeligo into the two host islands, using 25-million tonnes of fill extracted from excavations for the now-expedited Montreal subway system. The metro’s Yellow Line became a priority for the project owner, Montreal’s Bureau de metro, and by the opening of Expo there were 21 kilometres of subway with 22 stations completed. The Bonaventure and Decarie expressways were also wrapped by opening day. Meanwhile, the commission’s budget kept expanding — the original estimated cost of $167 million grew to $439 million by 1967.

Expo commissioner general Pierre Dupuy, a former diplomat, led a team that became known as Les Durs — The Hard Ones — for their drive to get the project done on time. Dupuy visited 125 countries asking for contributions and in the end 62 nations signed up. Joining chief architect Edouard Fiset in encouraging architects and cracking the whip on constructors were Pierre de Beaubien, in charge of pavilions, and Col. Edward Churchill, director of installations. Berton said it was Churchill who set up an esthetics committee to co-ordinate thematic coherence of the grounds, graphics and structures and who had the reputation of being prepared to push buildings into the river if they were not completed on time.

The pressure was squarely on contractors such as Desourdy Construction to deliver. Desourdy, now part of Eurovia, is credited with varied works including contributions towards construction of the islands and McKay pier and building a water treatment plant, several pavilions including 19 structures that were part of the Man the Provider pavilion and also various stations for the Expo Express train.

Moishe Safdie’s housing project Habitat 67 was not completed by opening day but it was decided to keep a crane on site to illustrate how the modular structure was being assembled, as a work-in-progress exhibition.

Crowds thronged to the 900-acre site on opening day, April 27, undeterred by the inconveniences of the sewage system breaking down 27 times the opening weekend and dust that initially marred the rides in La Ronde amusement park. The national and theme pavilions created the biggest buzz.

Nostalgic Expo fans contacted through an Expo 67 Facebook page were asked about their favourite pavilions. Their responses reflect the eclecticism of the architectural visions. Clement Drolet, who visited as a 13 year old from the Quebec City area, commented, "The first room in the Labyrinth was astonishing. Man in the Community particularly from the inside when it was raining was superb. The four pillar arches inside the Australian pavilion had something very relaxing. Architecture was everywhere at Expo 67, almost every pavilion had at least one interesting feature."

Kris Bennett said simply, "Katimavik!" That was the Canadian pavilion, the 270,000-square-foot, 100-foot-high inverted pyramid designed by Ashworth, Robbie, Vaughan and Williams Architects and Town Planners and built of structural steel and laminated B.C. fir wood.

Katimavik was a top-five draw along with the Russian, French, Czechoslovakian and U.S. pavilions. Facebooker Jean Cauvier discussed the Soviets’ contribution: "The USSR pavilion with its V-shaped support beams…the roof seems to float above the glass walls looking toward the future."

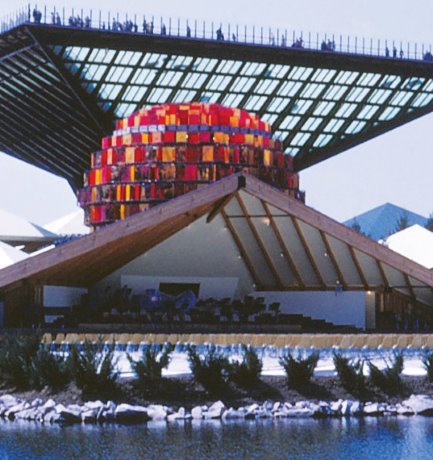

Raves about colours and geometry abound on the Expo Facebook fan site. John Bood said a favourite was the Kaleidoscope pavilion, designed by Robert Simpson Frew, Morley Markson & Associates and Irving Grossman for a group of chemical firms: "Colourful, round building. The Czeckoslovakian pavilion for the glassworks. Bell because of the surrounding movie."

Finally, from Randy Lopes: "I’ve always thought the Scandinavia pavilion was very attractive. It was much less showy than some of the larger pavilions but done in very good taste."

McGill University’s School of Architecture prepared an overview of Expo 67 design in an online project called Welcome to Expo 67: A Photographic Journey that has recently been reposted on Flickr. The archive consists of 470 photographs taken by Meredith Dixon, a McGill grad with a degree in mechanical engineering, curated in part by Marilyn Berger, then head librarian of McGill’s Blackader Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art. Now retired, she recalls those halcyon days, attending many times as the mother of a young family.

"We never complained of the long lineups at every pavilion as it gave us a chance to chat with those around us, mostly tourists from many parts of the globe. Our world was expanding. Montreal’s subway system had just started operating and it made travel to the site so much faster and easier.

"Meredith Dixon was diligent in documenting the site. The exceptional contribution of his slides given to McGill Libraries many years later gave me the opportunity to produce a digital version of an incredible event in the history of Montreal."

Highlights documented include the Israel pavilion, designed with hexagonal geometry, detailed so it could be dismantled and re-erected in Israel; and the Africa Place Pavilions, featuring "a natural flow pattern as a fundamental design intention. Each pavilion cluster was formally related to and spatially dependent on its neighbour. A natural ventilation system in the roof design added an underlying consistency to the roof forms."

Buckminster Fuller’s U.S. pavilion drew special praise from the McGill archivists and indeed from most visitors to Expo. It was described as "a marvel of structural design. This six-level geodesic dome was the first of its kind, specially designed to create a new environment through structure. The transparent acrylic domes set inside the steel structure glistened in the day and glowed from interior lighting at night."

Safdie’s Habitat ’67, located on the North Shore, now an upscale condo community, was another focal point. The McGill archivists described it as "a radical housing solution for the 1960s. It was a high-density alternative to the suburbs; an apartment structure (158 individual houses made up of one, two or three boxes)…an instant icon, the design of Habitat ’67 embodied a strong vernacular influence as the expression of its parts formed a striking whole."

Ewa Bieniecka said architects like her that started careers in Expo’s wake learned from studying the fair’s legacy.

"As an architectural student, I was always drawn to the analysis of what those people who had a vision created.

"Expo was built with a great amount of energy, and young architects and foreign architects who were coming to the country were putting in a blueprint of innovation… all that got built, talking about infrastructure on an international scale, getting the pavilions done, and pushing innovative ideas, I find that remarkable, that energy."

Expo 67 shut down on Oct. 29, 1967, its status as a brilliant episode in Canada’s cultural history secure. Reflecting years later, Pierre Berton recalled breaking into spontaneous tears on his five visits to Expo with his family. And writing just after it closed, Toronto Star columnist Peter C. Newman wrote, Expo was "the greatest thing we have ever done as a nation."

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed