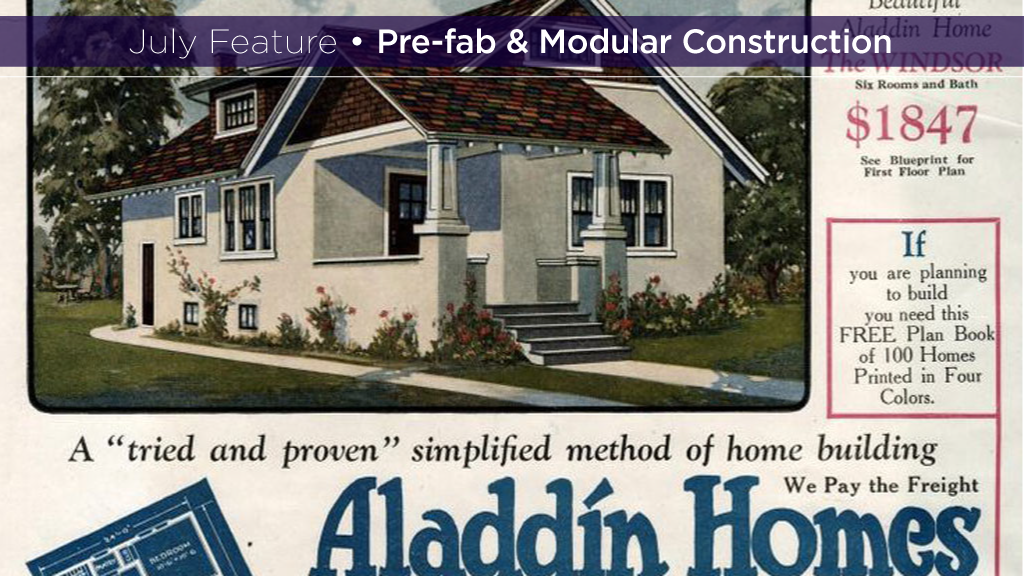

The cost of a mail order kit for a 1,200-square-foot model home named The Windsor was offered by The Aladdin Company across North America almost a century ago. The kit was delivered by rail and included all the pre-cut lumber a homeowner would need to assemble it without a saw.

1927 price: $1,795, freight included.

Even after inflation, that translates into a little more than $32,000 in 2024.

Could that price advantage be replicated today?

It’s an intriguing idea, says John Robinson, formerly an architectural engineering technologist with Robinson Residential Design in Regina.

But many of the factors that have increased the cost of housing today have overwhelmed the advantages these kit homes offered.

Kit homes became popular more than a century ago. The most famous brand was Sears Modern Homes, sold by Sears, Roebuck and Company, which first sold the kits in 1908.

Eatons followed suit a few years later.

Both companies sold enough lumber and other building components to complete the structures.

Only Aladdin, a U.S. company which also operated from depots in Vancouver, Winnipeg and Toronto, provided pre-cut-and-mitered kits.

According to the 1929 Aladdin catalogue: “The Aladdin readi-cut plan avoids wasting lumber when building. We plan the construction of our houses so there will be no waste. When we cut a length of material, we arrange to use both pieces. This saves about $18.00 out of every $I00.00 worth of lumber ordinarily used in building a home.”

What obviously didn’t come with the homes, Robinson notes, was the land they were built on. When kit homes were popular, building lots were affordable to most Canadians.

The basic Aladdin kits included wood and shingles, with the homeowner purchasing any required brick or plaster, which the company assumed could be bought at a lower cost locally. The homeowner was also responsible for building a concrete foundation on which to erect the kit.

Although Aladdin plans did not originally include a furnace, toilet, bathtub, bathroom sink, or kitchen sink, these items became part of the standard kit for most models in 1929. Homeowners received a discount for eliminating any items from the shipment.

“A lot of original buyers wouldn’t have a furnace,” Robinson says. “They would just use the cook stove to heat the home. They wouldn’t have a hot water heater. I grew up in an Aladdin Windsor home, which was wired for electricity in 1927, but wasn’t hooked up until the 1950s. It was pretty basic living.”

The building exteriors were usually cedar siding or stucco; higher-maintenance products than modern homeowners would likely tolerate.

The cost of wood building materials supplied by Aladdin has also increased faster than the general rate of inflation since 1927, clouding price comparisons.

“The standard package included tongue-and-groove flooring in every room and it was clear it was Douglas fir,” Robinson says. “But because there were so many old-growth trees, it was cheap. The siding was old-growth cedar with no knots and incredible quality. We’ve taken cedar siding off an old house, turned it around backwards and put it on a newer house — it just lasts forever.”

An Aladdin home could be built on a schedule ranging from a few weeks to about three months. Homeowners could save on labour by erecting an Aladdin home themselves, or with the assistance of relatives and a little professional help. Some chose to hire a crew to assemble the parts. Aladdin estimated its kit homes could save $30 per $100 by eliminating the labour involved in time-consuming cuts.

“Labour was a relatively small part of the overall price,” Robinson says. “You could probably get workers for $3 to $5 a day. Today you might be paying $100 an hour, so that’s a dealbreaker on savings.”

Fees and delays in permitting also add considerably to the cost of today’s homes and building codes have become very specific and localized.

“It’s hard to do a plan that fits everywhere,” Robinson says. “Today, a universal home kit would likely run into roadblocks.”

Aladdin stopped manufacturing homes in 1982 and closed its doors in 1987, but its initial premise is still sound and echoed by today’s builders of prefabricated and modular homes: “Modern power-driven machines can do BETTER work at a lower cost than hand labour. Then every bit of work that CAN be done by machine SHOULD be so done.”

Reminds me of the Sears prefab homes of the 1920’s http://www.searsarchives.com/homes/1915-1920.htm