Just because builders construct energy efficient buildings doesn’t mean they can clearly claim to doing their part to reducing CO2 emissions, indicates U of T experts.

In the fight to minimize the impact of global warming the type of building materials used play a major role in the equation. Kelly Doran, an adjunct professor at the Daniels School of Architecture at the University of Toronto and associate director, architect, White Arkitekter, say reducing emissions is not easy because “we are trained to build buildings in Canada” with problematic materials.

Of the 77 building products that make up a contemporary wood frame house, for example, 11 are comprised of oil, according to federal government sources, he points out.

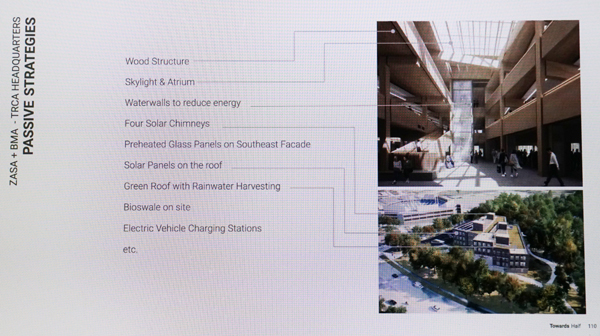

It is rationale for Doran’s research over the past two years at the University of Toronto through the Towards Half Studio on how to “half” embodied carbon (CO2 emissions) of all construction by 2030.

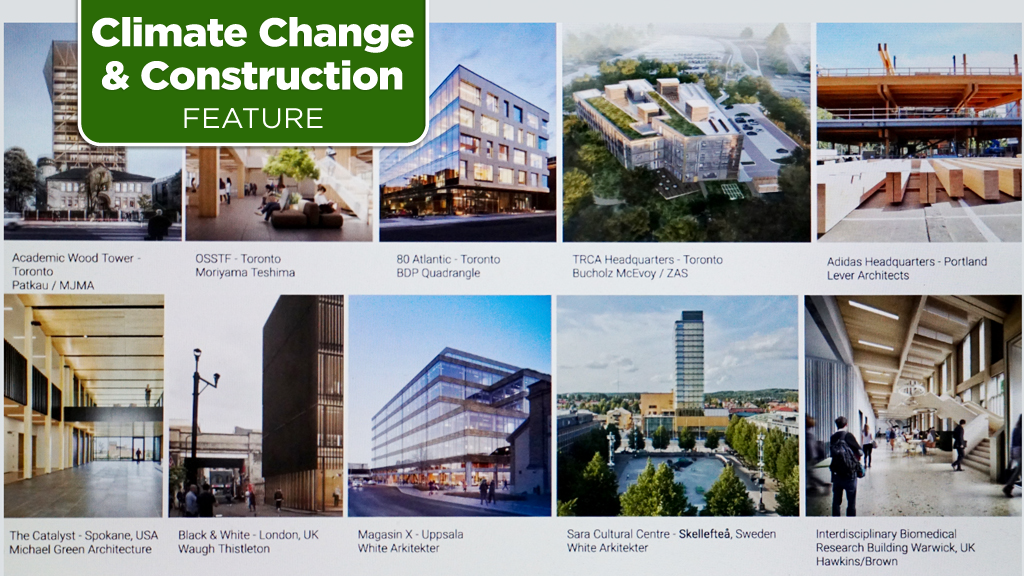

Doran’s study examined a variety of multi-unit housing types. His student research team looked at the embodied carbon of structures, envelopes and finishes and also performed life-cycle assessments. In year one, the team examined ten conventional multi-unit residential buildings in Toronto and in year two it focussed on ten mass timber residential buildings – some in Toronto, others around the globe.

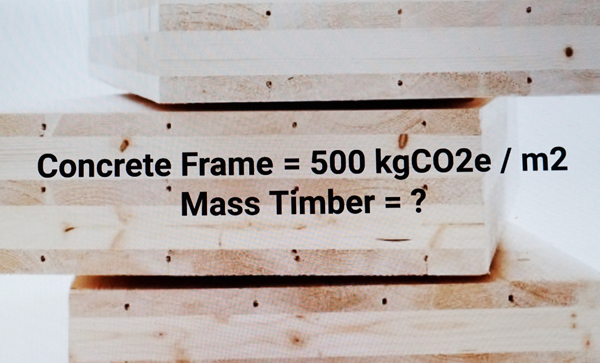

Data from the first year shows that total embodied carbon “varied significantly,” with low-rise wood frame townhouses seeing roughly half the emissions per square metre of their mid- and Highrise counterparts. Cast-in-place reinforced concrete has “by far the largest emissions,” says Doran, who hosted a webinar on the study with a focus on the benefits of mass timber at the Wood Solutions Conference organized by the Canadian Wood Council.

The data reinforces the need for policy makers and planners to find ways to incentivize and design lower carbon structural materials, he says, pointing out that some materials and designs can be refashioned or engineered to minimize emissions. A case in point is hollow-core concrete versus its cast-in-place counterpart. One of the buildings studied (Oben Flats, a residential project in Toronto’s east end) reduced embodied carbon by two thirds through its use of hollow-core rather than cast-in-place concrete slabs.

Facade materials in mid- to high-rise buildings play a big role in global warming carbon emissions, he says, pointing out that XPS insulation and aluminum-based extrusion glazing systems (curtainwalls and windowalls) have “the highest embodied carbon of all the material in the study.”

He recommends lowering carbon-emission envelopes through the use of different insulation materials such as wood fibreboard instead of XPS.

Another recommendation from year one buildings is to reduce or eliminate basements and underground parking because these spaces often represent a high percentage of a project’s footprint and they are made of concrete. A trade-off might be to provide equivalent space in a floor above grade.

Doran points out buildings have not always used so many unsustainable materials. Wood fibre insulation and stone foundations specified a century ago are examples.

At issue in the emissions problem can be modern building designs. Mid- and high-rise buildings with stepback designs facing south increase solar effect but north facing stepbacks require additional columns and transfer beams without the benefits of the sun.

The 10 mass timber buildings studied in the second year of the study showed “only minor reductions” of embodied carbon over the first year’s crop of buildings, says Doran but “significant reductions” result when biogenic carbon sequestration is considered.

Biogenic carbon emissions originate from such sources as soil, plants and trees, he says, noting that government policies and building codes should encourage the use of biogenic material such as mass timber, timber, hemp and other materials that can be grown.

Doran points out the facades of the mass timber projects studied show operational emission reductions over their unitized window- and curtainwall facade counterparts because of reduced window-to-wall ratios and the use of mass timber in the facade.

He says regional sourcing of materials – especially wood – can lead to “significant” emission reductions, but the shipping distance is not at issue as much as the energy source in production.

Doran is working with others and the City of Toronto through a grant financed by the Toronto Atmospheric Fund to build on the two years of data compiled in effort to develop the first embodied carbon regulations for the city.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed