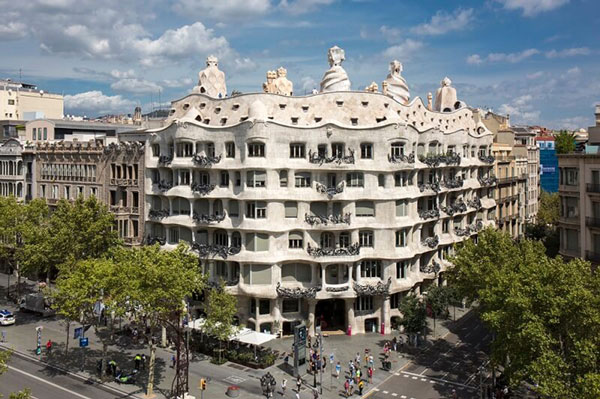

“If you’re looking for a low carbon, reusable material that is strong, robust and beautiful, stone is ready for a revival,” writes Steve Webb, director of U.K. firm Webb Yates Engineers.

There’s no doubt about stone’s long-term durability. Some of history’s most famous buildings were built of stone hundreds if not thousands of years ago. But what about other important considerations, such as stone’s impact on the environment?

The environmental argument for stone has inherent contradictions. Stone is at least as strong as either steel or concrete. Its tensile and compression strength means profiles can be smaller than concrete. On the other hand, stone is relatively heavy. Availability and supply are limited by geography. Transportation can be expensive.

Putting esthetics aside, Webb asks us to consider the accepted contradictions of today’s modern building techniques, describing how concrete is produced in ironic terms.

“We crush rocks into gravel. We dig up and pulverize limestone. In gas powered factories we burn the limestone to make cement. We dig up a lot of sharp sand. At state-of-the-art batching plants we mix them with water to make liquid concrete. With sophisticated algorithms and just-in-time management principles a fleet of wagons distributes it to building sites. We pour on the concrete. We vibrate, level and float it and then wait. A week later we strip away the formwork. After 28 days we remove the falsework. Hey presto! Stone again! In two months we’ve turned a lump of 230N stone into a lump of 40N concrete.”

In contrast, he suggests stone can be cut and used in construction quickly, with few intermediary processes.

In terms of credible Embodied Carbon (EC) calculations, Webb references the 2019 Inventory of Embodied Carbon and Energy. That database states “general stone” has 0.079 kg of carbon per kilogram of stone. By comparison, concrete comes in at 0.15 kg of carbon per kilogram and steel at 2.8 kg of carbon per kilogram. This suggests a clear environmental advantage for stone.

Comparing stone’s EC with that of mass timber is more complex. Certainly trees sequester CO2 as they grow. However, everything concerning the creation of mass timber, from tree harvesting, through production and transportation of Cross Laminated Timber (CLT), to mass timber’s end-of-life, negate those positive attributes.

Beyond today’s environmental concerns are safety issues affecting how and where certain building materials can be used.

Fire resistance is a key factor. Although not all stone is equal in fire resistance, initial testing Webb has conducted alongside ULC suggests stone offers superior fire resistance to concrete. That’s because the water content in concrete can cause spalling, possibly exposing rebar which can then fail. CLT has fire resistance issues as well, such as delamination that can cause more material to be exposed and burned.

Webb also notes some things can’t be built from mass timber anyway, particularly infrastructure.

“No one is proposing the first CLT nuclear reactor, or dam, but stone is great for infrastructure and has form in tunnels and bridges. Experience has shown that arch bridges are very durable structures requiring little maintenance in comparison to other bridge forms.”

The compressive strength of stone, superior to both steel and concrete in many instances, means less reinforcement is required, and allows stone to be used to resist shear and torsion. Furthermore, stone does not deform, aka “creep,” under load over time.

With so many positive characteristics in its favour, what is holding stone back?

“Engineers are hesitant to use stone because they simply don’t know how strong it is and they don’t have design codes or training to apply,” says Webb. “The possibility that it, like bricks, could support the entire structure let alone its own weight has not been taught because it was at first rejected, then forgotten.

“Used in the right way, stone has the capacity to be very slender, durable and elegant,” concludes Webb.

Unfortunately, its use over the past 100 years has been restricted to the occasional use on facades.

John Bleasby is a Coldwater, Ont.-based freelance writer. Send comments and Climate and Construction column ideas to editor@dailycommercialnews.com.

Recent Comments