Through efforts like the Living Building Challenge, we’ve seen a handful of Net Zero energy buildings, which produce as much energy as they consume and emit no carbon. Now, the concept is being extended to water, with a view to managing consumption and recycling stormwater and wastewater on site all while expending minimal energy.

Water bubbled up repeatedly at the Urban Ag Summit at Ryerson University in August. That’s hardly shocking given the green building movement and the 100-mile diet shared equal billing at this four-day international confab organized by Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, a North American trade and professional development association, and FoodShare, a Toronto-based booster of local food production.

At a four-hour mini-course on integrated water management for buildings and sites, developed by the Green Roofs group and the American Society of Irrigation Consultants, Kansas City-based landscape architect Jeffrey Bruce talked about closing the loop on water consumption in buildings.

“We use about two trillion gallons a year just to flush toilets,” Bruce said, citing U.S. Environmental Protection Agency figures for that country.

Canada, Bruce pointed out, ranks third globally in terms of national water footprint per capita, behind only the U.S. and Uzbekistan.

“There are enormous volumes of water that go unaccounted for in our system that we can tap into,” Bruce said. “And there are numerous ways to capture and use this water.”

Saving water is crucial, Bruce said, because areas currently rich in supplies might one day find these costly and unreliable due to factors such as climate change, lax environmental regulation and aging infrastructure.

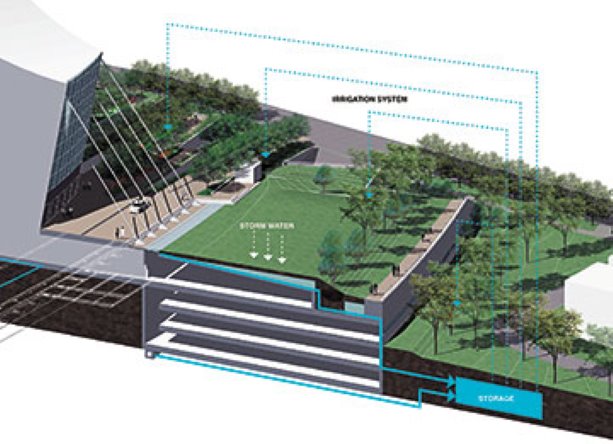

That’s where Net Zero fits in. Through a combination of tactics, including rainwater harvesting, aggressive conservation and measures to recycle and re-use water internally, buildings can work with nature to achieve water self-sufficiency rather than discharging it as waste.

Bruce said water use depends on a building’s occupants. Planners also need to consider the different grades of water, from potable tap water, to rainwater that becomes stormwater as it collects on surfaces and pools with various contaminants, to grey and black wastewater that’s undergone varying degrees of use indoors.

While it’s becoming increasingly common to find uses for rainwater, Bruce pointed to unconventional sources such as air conditioning condensate, backwash from swimming pools, and cooling tower and boiler blow-down. “About 90 per cent of all water used by industry is for cooling towers, so it’s a pretty good alternative water volume,” he said.

However, HVAC equipment can leave metal residues, and cooling towers leave salt residues from evaporation as well as biocides and algae inhibitors used to prevent outbreaks of legionnaire’s disease. Bruce said the various grades of water need separate pipes, and filters and processes such as reverse osmosis and ultraviolet lighting can help weed out contaminants, just as various technologies are used to treat stormwater.

The idea, Bruce explained, is to tap into each source on site, treat as necessary, and re-use as extensively as possible in ways that are safe and appropriate.

But it gets complicated. Rooftop gardens where food is grown require potable-quality water, yet rainwater harvesting isn’t considered efficient for immediate use for landscaping because landscape doesn’t need added water when it’s raining. Storage might seem sensible yet can be expensive.

Net Zero efforts can be subject to overlapping regulation through building, plumbing and health codes and by government departments overseeing the environment or natural resources. Bruce says regulators have been slow to appreciate Net Zero.

So, while it might be useful to blend water from air conditioning condensate with cooling tower blow-down, which has high salt content, in order to reduce salinity and get water acceptable for certain uses, it’s tough to achieve this in the current regulatory environment. “They don’t understand it, so we’re going to have to build that framework,” Bruce said.

Despite the hurdles, a few buildings have achieved Net Zero for water. Projects seeking certification through the Living Building Challenge must meet net-zero guidelines, and these include Tyson Research Center in St. Louis and Omega Center in Rhinebeck, New York.

There are further signs of hope. The Cascadia Green Building Council takes a net zero approach with the Living Building Challenge, which establishes a new standard for resilient buildings. And, ASHRAE certification prohibits the use of potable water for thermal conditioning.

Like other green approaches, Net Zero requires up-front capital and ongoing maintenance spending for technology. However, closed-loop systems ultimately reduce utility bills because they reduce intake from the grid.

Ultimately, it comes down to the building at hand. Older architecture like New York City’s Empire State Building often have limited roof space for water projects, while Net Zero efforts tend to be easier to implement in new designs and in a neighbourhood context.

“Net Zero is a considerable challenge but it’s certainly achievable,” Bruce said. “It’s essentially self-sufficiency where you get off the grid — where all waste streams, water-use streams and energy streams are internally cycled.”

1/2

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed