Samuel de Champlain would be awed.

Mapping Canada back in the 1600s wasn’t easy, to say the least. It took a lot of time and a lot of revisions.

Fast forward 400 years and digital technology continues to change surveying on a continual basis. Mobile capture has been around for a few years but what’s trending is the convergence of several modes of data while the equipment itself gets smaller, lighter, more responsive and consequently more mobile.

"There’s still a lot of skilled work which relies on experience and knowledge which has to be done after the data is captured but we are getting faster at it," said Stuart Wood, Geospatial Division at Leica Geosystems’ vice-president, which introduced the Geosytems Pegasus Two, a vehicle-mounted HDS scanning system two years ago.

To Champlain’s awe, it can perform 360-degree corridor surveys at more than 50 miles per hour.

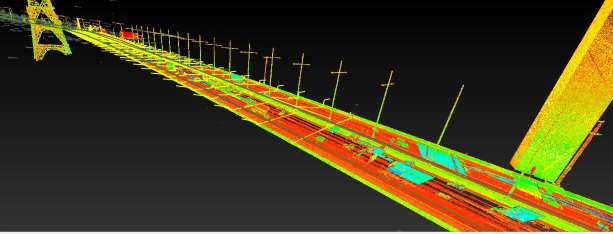

What’s more interesting is that it captures a host of different data types simultaneously, with laser scanners working with (Global Navigation Satellite System) GNSS receivers, Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) and a Distance Measurement Instrument (DMI).

The platform is turn key including cameras and lidar profilers with an external trigger and sync output for additional sensors.

"What has really changed is that now we have the ability to capture data and then go back to work on it in an environment which is more comfortable," Wood said.

Traditionally survey crews mapping a construction site or roadway in remote locations would have to fly in and out constantly, over an average of 29 days or more, which dramatically increases costs.

With digital and mobile capture, the time at site is reduced to as little as two days, which is a substantial cost savings, Wood said. He noted that Leica Geosystems is part of Hexagon, a global provider of information technologies for productivity and quality control across geospatial and industrial enterprise applications and sees global applications for their product.

There’s still 15 to 29 days of data processing, highlighting and analysis to be done but software developments are looking to cut that time down further too. The data also already synchs up with standard CAD programs.

Wood said the system is truly mobile, weighing a total 70 kilograms and shipping in three cargo crates to the location where it can be mounted on a local vehicle.

"It’s totally independent of the vehicle itself with its own battery supply," he said. The battery has about 20 kilograms of the total weight.

"When you’re surveying a road for an extension or addition like a roundabout, you have live traffic and this is a very safe and efficient system," he said. Since it’s mobile there’s no need to shut down traffic causing gridlock and it’s much safer for the survey crew who simply drive in traffic at normal speeds.

The self-contained platform has been used in remote and harsh conditions, including mapping out 400 kilometres of new roadway in Niger, Africa, Wood said.

In Canada, with its vast remote areas, Quebec has been the early adopter of the technology and it is being used in the oil patch, military bases, in general locations without a lot of supporting infrastructure.

For urban municipalities, the selling point is that the platform can capture a host of data for future references just by driving around, like Google has done with its mapping vehicles.

The difference, said Wood, is that both visible and invisible features can be captured.

A second variation involves a trailer rigged with ground penetrating radar which can also quickly be towed over roadways to capture underlying features. A backpack version is also offered to map the interior of buildings.

The latter allows for documentation of a building consistent with collecting 4D data — the basic 3D data with time as the fourth dimension — cataloguing the construction progress and recording infrastructure before it is embedded and invisible to the eye. Another level is 5D, which includes costs, as another layer of dimension for BIM (Building Information Modeling) systems while 6D BIM is a compilation of all systems.

"It allows for future reference as to where the electrical might run behind a wall when changes are contemplated," said Wood, noting the system launched in June this year and will be available in September.

Finally, the other rapidly developing technology in surveying is with drones, also called Unmanned Aerial Vehicles.

Again, a convergence of smaller, lighter electronics along with more powerful flying platforms with simple control interfaces, has opened up more terrain for faster surveying.

"Especially in remote areas, you can’t always get to the location and you don’t know what’s over the next hill," Wood said. "Also, there’s a safety factor, you’re not putting the surveyor or operator close to a wind turbine or something like that. Our products have enclosed, protected rotors for added safety."

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed