Researchers at the University of Waterloo have developed a tiny, new, battery-free sensor that uses nanotechnology to power itself and can detect water leaks in buildings and automatically send an alert to smartphones.

The sensors can be installed in previously inaccessible places as they are only five millimetres in diameter and are comprised of stacked nanoparticles. When they are exposed to moisture a chemical reaction occurs to produce electricity.

Researchers figure because there is no battery and related circuitry, they can be commercially produced for US$1 each, a fraction of the cost of current leak detection devices on the market today.

“The technology is very unique since it allows you to avoid using batteries,” explains George Shaker, an adjunct assistant professor of engineering at Waterloo, one of the brainchilds of the sensor with Norman Zhou, a professor in the university’s department of mechanical and mechatronics engineering and department of electrical and computer engineering. “It is environment friendly and very low cost. No battery maintenance or replacements are needed.”

Shaker oversees wireless activities in the sensors and devices lab at the UW-Schlegel Research Institute for Aging and Zhou has his own lab at the university. Graduate students of the professors were also involved in bringing the idea to reality. The team included student Oliver Witham, postdoctoral fellow Ming Xiao, research associate Jiayun Feng, physics and astronomy professor Walter Duley and graduate student Nathan Johnston.

While water leaks are a big cause of damage and property losses in offices, apartments and other buildings, Shaker says many owners don’t install enough sensors during the construction phase because they are too expensive.

We believe this has the potential to solve several important problems,

— George Shaker

University of Waterloo

Sensors typically range in cost from $50 to $100 because they have complex battery management systems to support their onboard high-power radio.

“At this price range, it’s very expensive to deploy thousands of these units in real life application cases,” says Shaker.

In addition, the more costly the units, the more complex and expensive the solution is because such systems involve higher operational costs to cover issues like battery replacements.

“Needless to say, the more the units, the more the battery waste, and the more harmful the system would be to the environment,” says Shaker. “We simply wanted to create a better and environment-friendly system.”

He says the lower cost of the sensors developed by the Waterloo researchers opens the door to deployment of many more of them to monitor leaks and greatly improve protection in buildings.

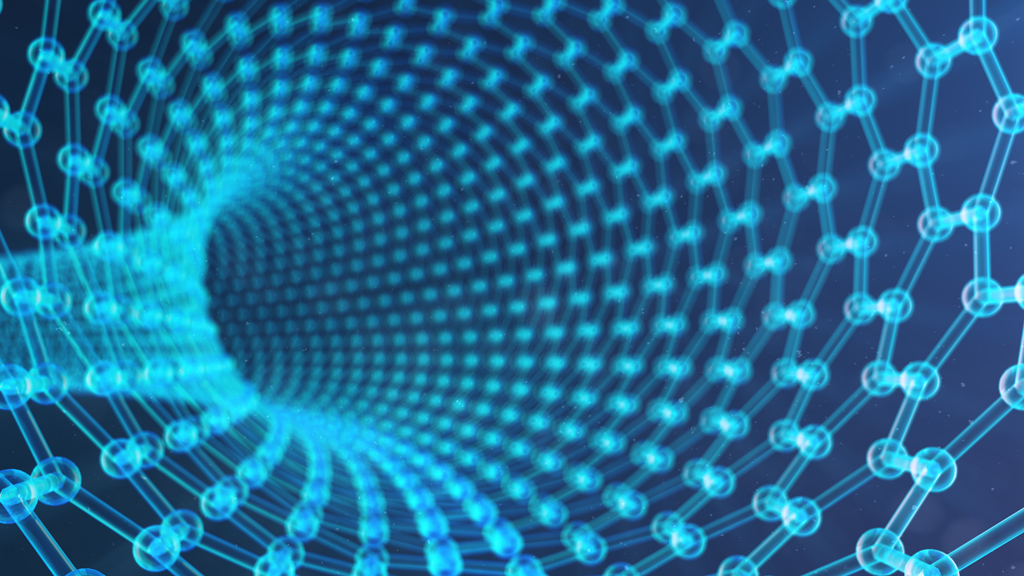

The new sensor is based on nanotechnology which is the study and application of extremely small things, normally at the scale of one to 100 nanometres. To put things in perspective, there are 25.4 million nanometres in an inch. A sheet of newspaper is about 100,000 nanometres thick.

Nanoparticles generate electricity when exposed to humidity, water or any other liquid. The basis of the battery-free sensor is a tiny white cube just a few centimetres square. Inside the cube, is an energy harvesting board. Upon a water leak, the nano materials inside the cube activate and generate electricity to power an onboard wireless radio. This process all takes place inside the cube.

The system can be set up so that when a leak occurs an instant notification is sent directly to a smartphone.

“The radio will send an SOS signal to a wireless network,” says Shaker. “The signal will reach the clouds where our servers will direct an alert to the proper phone number and user app installed on the user’s cellphone.

“We can simply design the nanomaterials to only activate based on certain volumes of the liquid that come in contact with the material. The generated electricity is significant enough to power the wireless radio on other utility sensors.”

According to Shaker, a unique feature of the sensors is that they can be installed during building construction in very hard-to-reach areas. They require less maintenance and are therefore a greener way of detecting leaks. They also reset after use.

After a building is erected, typically the only way to install a leak-detection system is by drilling holes or other destructive means to place them in a structure.

“For comparison, doing so with battery systems will typically mean that another destructive process is needed to be able to reach the system and replace the batteries,” says Shaker.

A paper on the research, entitled Development of Novel Water Leak Detection Mesh Network Utilizing Battery-less Sensing Nodes, was presented at a recent international conference on smart cities and the Internet of Things.

Now the researchers are busy working on building a Canadian manufacturing facility in Waterloo to support their mass production plans. They completed a pilot demo with a large Canadian condo operator and are presently growing a team to meet the high demand.

While they explore commercialization, researchers are also pursuing additional applications for the underlying technology, including in diapers for the elderly and in bandages to detect wound leakage after surgery.

“We believe this has the potential to solve several important problems,” says Shaker.

Where in the building do you install these nanometers?