Robotics and automation are transforming the way we work, live and play. However, the construction industry is still dawdling at the back of the pack, according to numerous studies and reports.

Arash Adel, an assistant professor of architecture at the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan, is doing his part to change that.

Adel, along with research assistants at his ADR Laboratory, and students in the masters program in digital and material technologies at Taubman College, built a novel wood pavilion at Matthaei Botanical Gardens in Ann Arbor that showcases how robotics can be used to create complex structures.

The project was geared to promote sustainable low-carbon construction but also demonstrate how human-robot collaboration could work – and one day be extended to building new homes.

The aptly named Robotic Fabricated Structure (RFS) featured a curved tunnel consisting of thousands of pieces of wood with bench seating on the exterior.

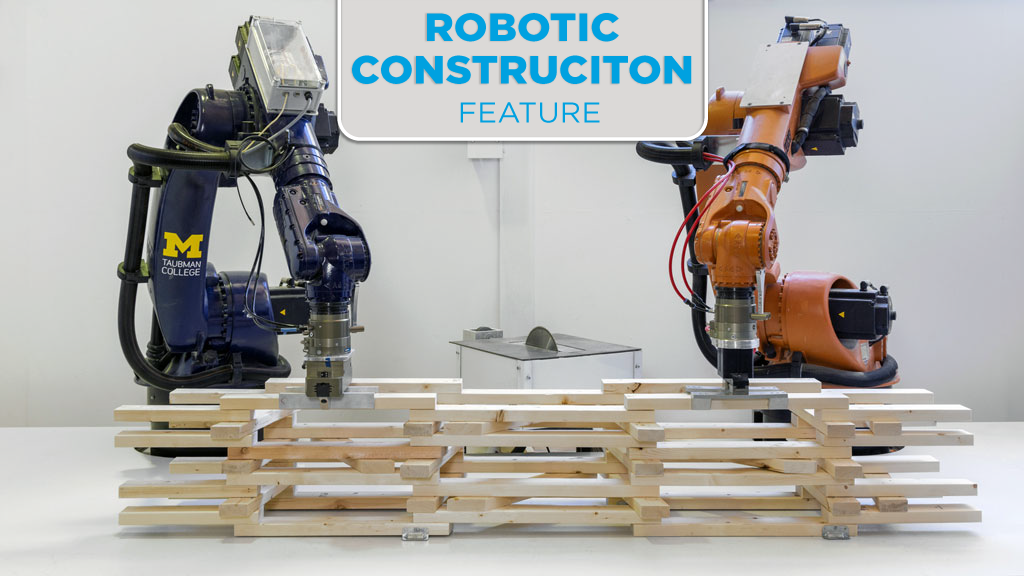

Industrial robotic arms were used to fabricate custom timber sub-assembles in the lab from off-the-shelf lumber.

Adel is hoping the case study promotes conversations about appropriate uses of automation in construction and the architecture, engineering, and construction community’s shifting responsibility to find creative solutions to construction industry inefficiencies and the omnipresent threat of climate change.

“We are fully invested in advancing the larger questions of how and why we make, and in discovering and testing new ways of building the future,” Adel stated. “Completing RFS enabled research in robotic timber construction to be elevated to the scale and complexities of full and complete building systems beyond the laboratory.”

Using algorithms that were specifically designed for the project, researchers and students at Taubman’s digital fabrication lab used the robotic arms to process the material and assemble the elements into intricate modules. The modules were then transported to the site and assembled by hand to form the pavilion.

The coupling of custom algorithms and robotic fabrication enabled the parts to fit together seamlessly and with minimal construction waste.

Adel says the project proved that robotics could help with sustainable low-carbon construction projects.

“I think that was the main goal that we achieved. But a critical thing is that it showed it needs to be coupled with an algorithm because the robots are like, dumb, and they need to have a suitable algorithm.”

ADR conducts research in the area of human-robot collaboration and has been working out how to develop algorithms for specific projects. The wood pavilion was an opportunity to put research into action.

The team of researchers and students partnered with engineering firm Silman to evaluate the pavilion for structural performance and building code requirements.

Custom algorithms were used to calculate the optimal arrangement for the timber, removing the need for any larger beams within the pavilion. The algorithms helped because there were many small pieces of wood that needed to be fitted together to form the modules, a task that would have been difficult for humans.

The algorithms also enabled the wood to be processed much quicker and the cuts to be done more precisely. All of the modules used in building the structure were slightly different which gave the pavilion an undulating shape.

“What we wanted to do here was offload the difficult tasks such as cutting the timber,” says Adel. “We left a lot of the measuring to the robots. The algorithms were constantly checking all the elements, for example, the length of the cuts and if the pieces were connected properly.”

The pavilion was made of 20 robotically fabricated frames.

The structure was installed on an oval-shaped timber platform. The intent was to design it as a place where people could gather but still maintain an open-air condition. The design and configuration of the pavilion was influenced by views to and from the site. The structure blended into the surrounding natural landscape.

The pavilion also included an enclosed walkway. Intricately layered patterns of timber were featured on the walls and ceiling that allowed for airflow, striking shadows, and optical effects. The wood of the structure was left untreated to reduce the environmental impact and to allow it to be re-used on another project.

For the most part, the project went as planned, Adel says. But there were a few challenges. For example, the 2x4s used for the structure were not always exactly the right dimensions so they had to be adapted.

When the pieces were assembled on site, the pavilion also ended up being slightly larger than anticipated but it was easily resolved by modifying the foundation on the site.

The pavilion has been long-listed in the small building category of the 2022 Dezeen Awards, an international competition that highlights the design excellence of projects that benefit users and the environment.

A prototype of the technology was also on display at Taubman’s Liberty Research Annex Gallery which provides space for students to showcase projects.

The pavilion, meanwhile, is now being dismantled, in line with the original plan. The wood will be re-used on another project.

“We are making an inventory of the elements and will continue our research for the build of our next project,” says Adel.

Interesting proof-of-principle. But to have a significant impact, it would need to scale up to the complexity of, say, a house’s structure?? Or even a garage’s? The algorithms would seem to be a bear, likely beyond the practices of the typical builder or architect.