Part one of Cracks in the Foundation: Mental Health, Substance Use and Construction, examines the current state of substance use across the country, with experts painting a picture of how the industry has been specifically impacted. The fourth and final article in this DCN-JOC Special Feature Series delves into the numbers in the United States and the lessons being learned south of the border.

The fight against opioid misuse and suicide in the U.S. construction sector is often a personal as well as a professional mission for the stakeholders trying to come to grips with these persistent stains on the industry.

St. Louis has been an epicentre of treatment in recent years thanks to committed teams from the St. Louis-Kansas City Carpenters Regional Council, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the constructor Alberici, the Associated General Contractors of Missouri (AGCMO) and others.

John Gaal, retired director of workforce development for the Carpenters in St. Louis whose son committed suicide after suffering football-related concussions, speaks with messianic zeal about the causes of opioid misuse in the construction sector going back decades, with Congress, the Centres for Disease Control (CDC), drug companies and doctors all to blame for supporting misguided treatment plans.

He remains active preaching “total worker health” to deal with opioid misuse.

“It’s all interconnected when I talk to groups, I tell them, when I first started out I had three pillars, I had mental health, addiction awareness and suicide prevention,” said Gaal. “Sadly, they’re all under the same umbrella now. Often pain leads to depression and too often depression leads to suicide.

“And sadly, when it comes to construction being an industrial sector, we’re number one when it comes to opioid use, we’re number one or number two when it comes to suicide.”

Sal Valadez, a LIUNA safety manager in Missouri, recently wrote that a study from the Midwest Economic Policy Institute discovered that as many as 60 to 80 per cent of the workers’ compensation claims in the construction industry involved opioid prescriptions for injuries incurred on the job.

Valadez also reported that according to a 2019 report from the Missouri Hospital Association, the economic cost of the 47,576 opioid overdose deaths in 2017 in the U.S. was estimated at $634 billion.

Construction work generates a perfect storm of factors leading to opioid addictions and suicides, starting with the fact that workers are at high risk of injuries, making them at greater risk than other workers to be prescribed opioids that may lead to addiction, states the AGCMO. More than half of those who died from an overdose had suffered at least one job-related injury; four of five people treated for opioid misuse started on pain medications; and one of four people who are prescribed opioids for long-term pain become addicted to them.

The CDC wrote in its 2019 drug-use Surveillance report that the opioid crisis has gone through three phases, the first of which, in the 1990s, was abetted by the collusion of the CDC, drug companies and doctors to expand the use of opioids to treat chronic pain in addition to acute pain, Gaal said. The third wave began in 2013, when overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl, began to increase significantly.

Washington University associate professor Dr. Ann Marie Dale has been working with the Carpenters, the AGCMO and others on the health of construction workers for many years and the partners moved from the “low-hanging fruit” of trips and falls to the mental health of construction workers around the time of the 2007-08 recession, said Gaal. A confluence of the precariousness of finding work with jobs always ending, working away from home, high-stress work, an unsupportive organizational culture and the stigma associated with tough-guy culture was leading to new levels of stress as the recession took its toll.

“I could see that our apprentices needed more help, not so much with the physical aspects of safety but rather the mental aspects of safety. Washington U told me there was a term for that, total worker health,” said Gaal.

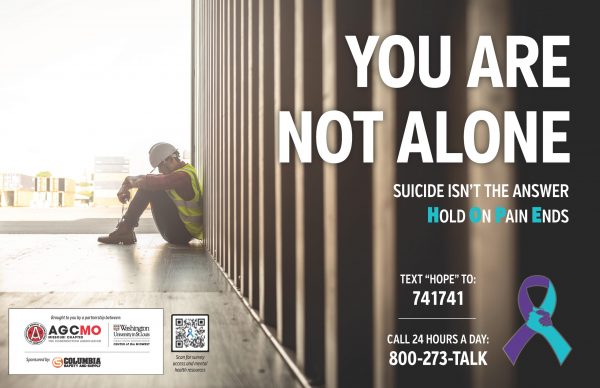

Of all the factors that have to be addressed, said Brandon Anderson, vice-president of safety with the AGCMO, stigma comes first. He has personal knowledge of drug misuse involving friends, family and himself that has cost lives.

“We have taken the approach of, just start the conversation and break the stigma, it’s OK to ask for help,” said Anderson “And we’ve taken a step further and have coined the term ‘HOPE’ — hold on, pain ends. And we’ve been asking everyone to spread a message of hope, and that it’s OKto not be OK.”

Gaal said the continuum of policy-making includes awareness, prevention and intervention. He said local and national awareness of the need for specialized opioid misuse programs for the construction sector is only about six years old but there has been significant progress.

He said the anti-opioid campaign requires harnessing resources from all sources including labour, employers and government, and conversations should start early, with new apprentices, he said.

“An important place to start is looking towards your joint labour-management training, committees. It’s incumbent upon that to ensure that the apprentice is developed 360 degrees, not just on the technical stuff but on the mental stuff as well,” he said.

Gaal has written that strategies include new approaches to pain management, analyzing claims data to detect potential drug problems and limiting pain medication. Even financial literacy can play a part, he said, to help apprentices deal with the stressful vagaries of their income flows.

St. Louis has been a key hub for the effort but there are movements taking shape across the country. The AGCMO and the Carpenters in conjunction with Washington University, the Center for Construction Research and Training, North America’s Building Trades Unions and many others have created toolbox talks and other programs. Gaal has written about an eight-hour certification course called Mental Health First Aid that can help supervisors and peers identify employees who require counselling before they turn to masking their problems with addictive substances.

Australia has taken the lead on overall mental health issues in the construction sector, Gaal noted, while the Case Management Society of America’s Opioid Use Disorder Case Management Guide is now viewed as seminal for case managers and health care professionals.

As the CDC began to recommend alternatives to opioids for treatment of chronic pain within the past half-dozen years, doctors have reformed their prescription practices, adopting what Gaal said is a “go low and go slow” approach.

“The medical community in the United States has really kind of tightened up the process for prescribing opiates,” Alberici safety director Bo Cooper said. “First, they tried different modalities to control pain…They’re going to be more willing to try other things first before they go to that for chronic pain treatment.”

Part two of Cracks in the Foundation: Mental Health, Substance Use and Construction, released later this fall, will feature firsthand accounts of those who have lived with an addiction in construction.

Follow the author on Twitter @DonWall_DCN.

Recent Comments