It’s called “reconnecting” two distinct communities.

One is on Detroit’s near east side, the other is the urban core.

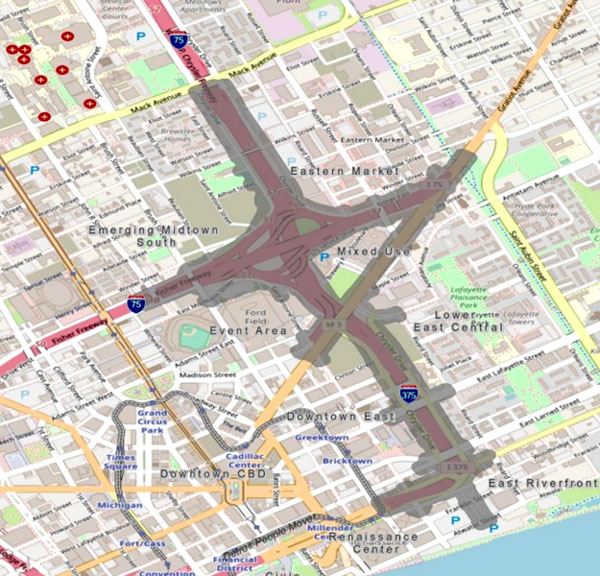

The project, announced by the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) in 2021, is designed to eliminate a literal ditch that eviscerated two historic African American business and residential districts (Black Bottom and Paradise Valley) and create an auxiliary interstate highway, I-375, which opened in the early 1960s.

The sunken two-to-four-lane expressway is the second shortest in America, just over a mile long, mainly built to accelerate traffic from the city’s downtown into Detroit’s vast network of freeways, especially northbound I-75, one of several such arteries built at the time which contemporary critics have said not only enabled massive suburban sprawl but “white flight” to the suburbs, leaving the city the most segregated in the United States.

Canadians are well familiar with the freeway since it’s located less than one kilometre east of the Windsor-Detroit tunnel, and is often used by Windsorites to drive to metro Detroit’s suburban shopping malls.

Now MDOT wants to dig up the ditch and fill it in with a surface arterial boulevard that would create seamless connections east-west and north-south between downtown and near east side residential complexes and from the Detroit River to the city’s entertainment district, Detroit Medical Center and Eastern Market.

The boulevard’s current plan would also have six lanes – as many as nine for turning – but with signalized intersections, sidewalks and bike lanes, with a natural median in between. A new interchange connecting I-75 is also slated.

The project would also solve the problem of having to replace seven deteriorating freeway overpasses.

The state says the project would not just “improve connectivity” but strengthen transportation through “multimodal personal mobility choices.”

And improved access “enables future development” particularly along an east side strip of 30 acres that would be freed for future use after construction is finished.

Construction is expected to start in early 2025. The total cost is $300 million with the U.S. Department of Transportation awarding the state $104 million a year ago. Federal, state and local partners would pay the balance.

Having decided on a preferred alternative, the state is now receiving public feedback on the final design.

While the community appears supportive of the project because of its goal of strengthening neighborhoods and creating density there are criticisms.

These relate to the revamped artery design itself, which critics say wouldn’t be a large improvement over the freeway ditch.

Bryan Boyer, a nearby resident and professor at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, calls it “a freeway by another name.”

This defeats several purposes, he says.

“That’s not going to be a safe place for pedestrians, it’s not going to be a place that is welcoming for local business. Cafes are not going to want to face that kind of street, housing is not going to be pleasant facing that street.”

Boyer, a member of the local advisory committee, thinks any intransigence comes from institutional bias.

“(MDOT) is going to do what they are built to do, which is create freeways and big roads,” he says. “The problem is this is not a freeway project, this is a project about the city that happens to have a road as part of it. So, let’s say the cart was put before the horse.”

Boyer says what needs to be questioned are the underlying values.

“It simply cannot be all about the road, it has to be about the place when the project is done.”

Moreover, the project runs roughshod over two historical communities.

“This just isn’t any old part of the city that was destroyed by a highway this was Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, which were the center of Black life in Detroit.”

One physical area that offers development potential is a freed-up the east side ribbon of land. The City of Detroit’s so-called framework plan “will inform what the use of those parcels are.” But Boyer called this late in the process for something that has been discussed since 2017. And he said it’s “impossible” to finalize road design “until we have a sense of what those lands would be.”

MDOT has also been criticized for token responses to acknowledge the old commercial neighborhoods, indicating it would erect signs and plaques.

“There has to be a proper kind of reckoning across the community of Detroit to collectively think about what should happen there,” Boyer said.

MDOT said other “historical environmental injustice” mitigation could be affordable housing and opportunities for minority business.

Antoine Bryant, director of Detroit’s planning and development department, said strides are being made to tweak final design. He said a revamped traffic study might be key, the last one in 2017 “we know was pre-pandemic.” He said work and travel plans “have changed pretty dramatically.”

Bryant said, “we foresee that there will be a revisit of what the alignment will look like,” including fewer lanes.

“I’m very confident in saying it will not be the same thing just at ground level.”

This includes safe pedestrian crossings and more traffic calming.

Bryant said the undeveloped ribbon of land is still MDOT property.

“We do have some very limited authority about what can happen” but the city is undertaking a zoning and land use study to conclude the property’s best use. Likely the land will be mixed use and “be very vibrant adjacent to downtown” and “amenable” to the abutting east side neighborhood of highrises and modern townhouses.

MDOT spokesman Rob Morosi confirmed “there is the possibility of a design change” for the road itself. As for the east side land, his agency is working with the city and residents “to determine the best possible outcomes for future use.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed