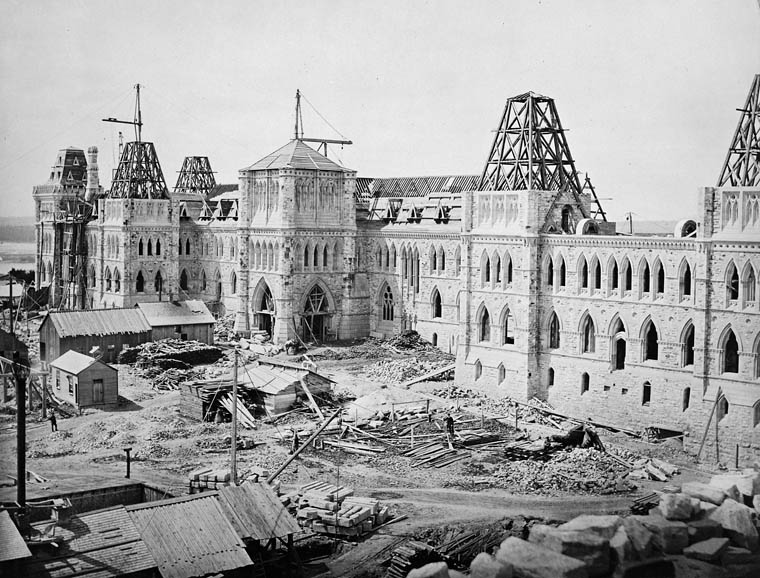

The construction of Canada’s parliament buildings in Ottawa was no small feat and the project took years to complete, but through it all they have remained a symbol of national pride and an iconic landmark.

Also known as “The Hill,” the grouping of three gothic revival buildings constructed in the 19th century is situated on top of a cliff in downtown Ottawa overlooking the Ottawa River. The buildings were completed in 1865 and represented one of the largest projects in British North America at the time and one of the finest examples of gothic revival architecture.

“It’s indicative of the high Victorian gothic revival style when you have pointed arches over the windows and doors, many vertical elements that reach upward towards the sky, highly decorative in the sense that they have all the tracery around the windows, all the corners of the building have a cut stone quoits,” explained Ezio DiMillo, director general at Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC).

Located on Wellington Street in Ottawa, the site where the Parliament Buildings stand was carefully selected by Queen Victoria. The Queen chose Bytown, now Ottawa, as the capital of the United Province of Canada in 1858. Barrack Hill was chosen as the site for the new Parliament Buildings because it sits far from the American border and is located on a cliff to make it easier to defend from a possible attack, according to the PWGSC website. The land was also already owned by the Crown.

Due to the proposed large scale of the Parliament Buildings, the then Department of Public Works organized an architectural competition to find suitable architects to design three federal buildings — a Parliament Building (Centre Block), two adjacent administrative buildings (the East and West Blocks) and a Governor General’s residence which never came to fruition.

The design of Thomas Fuller and Chilion Jones won first place for the Centre Block and Thomas Stent and Augustus Laver’s designs were selected for the East and West Blocks. The gothic style was chosen and was seen to reflect the style used for the British Houses of Parliament built during the 1830s.

According to the blog Today in Ottawa’s history, written by James Powell who is also a member of the board of directors of the Ottawa Historical Society, the government specified that the legislature building, totalling 55,000 square feet, was to contain a council chamber and a hall of assembly for the upper and lower houses of Parliament, a library, a picture gallery, 85 reading rooms, speakers’ apartments, committee rooms and clerk rooms. The two departmental buildings, which together amounted to roughly the same square footage as the legislature building, required 170 offices to house the entire Canadian public service.

Thomas McGeevy was awarded a contract to build the Parliament Buildings in 1859. After the ground was broken, the departmental buildings were handed over to Jones, Haycock and Company of Port Hope for construction and McGeevy retained the contract for Centre Block.

Ground was broken and the sod was turned for the new Parliament Buildings on Dec. 20, 1859.

“When they were building these buildings they didn’t have mechanical cranes, they had lifting cranes of some sort but they didn’t have the technology we have today,” said DiMillo, adding some of the challenges were manpower, transporting and storing the materials on the site. “Much of the work was done by hand and heavy equipment and construction elements were shipped by horse and wagon.”

According to DiMillo, the buildings were designed to be polychromatic on the exterior. The architects wanted the buildings to have slate roofs which have a grey-blue colour and the masonry a nice buff sandstone that came from Ohio. They used locally quarried Nepean sandstone as the more common face stone or wall stone and they used Potsdam sandstone for detail elements which has a reddish colour.

“Then when you put it all together along with the cresting on the top of the buildings, the wrought iron decorative elements that you see on top of all three buildings, they wanted to bring forward this multi-colour sort of effect,” DiMillo explained.

By 1861, public works reported $1.4 million had been spent on the project, two-and-a-half times more than planned. The site was shut down in September and construction halted.

In June 1862, a commission of inquiry investigated the project’s management problems and found some of the things that led to cost overruns were improper awarding of the construction contract, failure on the part of public works to appropriately assess the depth of the bedrock, failure to properly factor in the cost of heating and ventilation and inadequate monitoring of the construction progress.

Construction resumed in 1863.

“As you can imagine the population of Ottawa was 15,000 in 1860 and thousands of workers were brought in to work on the site,” said Powell. “Think about all the complications of building such huge monumental buildings in the middle of the wilderness, it’s an extraordinary achievement…just bringing in the materials and men was a huge undertaking.”

The Parliament Buildings officially opened on June 6, 1866, about a year before Confederation, which took place on July 1, 1867. Though they were not fully complete, the buildings became the seat of government for the four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and the first session sat Nov. 6, 1867.

Manitoba, the North West Territories (now Alberta, Saskatchewan, Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut), British Columbia and Prince Edward Island joined confederation in 1870.

By 1876, the Library of Parliament and the landscaped grounds were complete and later that same year the iron Queen’s Gates were erected at the main entrance of Parliament Hill.

As the country grew, so did the buildings on Parliament Hill. From 1906 to 1914, additions were made to all three buildings, new buildings were constructed and some federal departments moved off The Hill.

On Feb. 3, 1916 a fire started in the Centre Block and only the library survived thanks to its iron fire doors. When it was rebuilt a few years later the building was enlarged and the peace tower was completed in 1928 to honour those who died in the First World War. The gothic style of the building was retained by architects Pearson and Marchand but updated to a Beaux-Arts axial plan with gothic details. The rebuild was complete by 1920, four years after the fire.

On Feb. 3, 1916 a fire started in the Centre Block and only the library survived thanks to its iron fire doors. When it was rebuilt a few years later the building was enlarged and the peace tower was completed in 1928 to honour those who died in the First World War. The gothic style of the building was retained by architects Pearson and Marchand but updated to a Beaux-Arts axial plan with gothic details. The rebuild was complete by 1920, four years after the fire.

According to the PWGSC website, “a team of architects produced a design that, while similar to the original, used newly developed structural techniques and materials. The new Centre Block would also be larger and a full storey higher than the original building. To avoid another tragedy, instead of wood, interior walls are built with limestone and floors with marble. The exterior frame is made of steel and covered with the same Nepean sandstone that was used in the original buildings. Because of the war, materials and labour were in short supply and expensive, slowing construction.”

Over the years there have been discussions to rehabilitate various parliamentary buildings. In 1952, a fire nearly destroyed the library but instead of building a new one, the existing library was rehabilitated. In 1961, there were discussions to replace both the East and West Blocks with modern office buildings, but instead, the interior of the West Block was renovated with modern offices to replace the old Victorian rooms.

In 2002, a major program to rehabilitate the Parliamentary Precinct began. The long-term vision and plan is a multi-decade strategy to renew the precinct and includes fully restoring and modernizing the older buildings inside and out; preserving the buildings’ architectural heritage character; and ensuring that the buildings meet safety standards.

West Block rehabilitation work is currently underway. Due to the fire of 1916, the West Block is the oldest of the Parliament Buildings. The new building was designed by Arcop Architecture and Fournier Gersovitz Moss and Associates Architects, in a joint venture. PCL Constructors Canada is the construction manager on the project.

“You have to think that these buildings have not had any real major work, in the case of the West Block, in over 100 years,” said DiMillo. “We are basically taking these old heritage buildings and seismically reinforcing them, that is always a challenge when you are working with some of the older buildings and more specifically for a building like the West Block where it’s a load bearing masonry construction.”

Another challenge is bringing the buildings up to date and into the 21st century.

“These are gothic revival buildings that were built in the mid-1800s and they didn’t put in modern air-conditioning and heating and communication systems, security and multimedia,” said DiMillo.

“A big challenge has been putting all these modern systems in a heritage building but we have risen to the challenge with the help of various teams — the contractors, the architects and engineers — we’re close to opening the building (the West Block).”

1/3

2/3

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed