In 1998, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and World Resources Institute established the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GGP).

The objective was to set an international standard that would allow corporations to calculate and report greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). The first set of standards was published in 2001. Since that time, they have been revised several times.

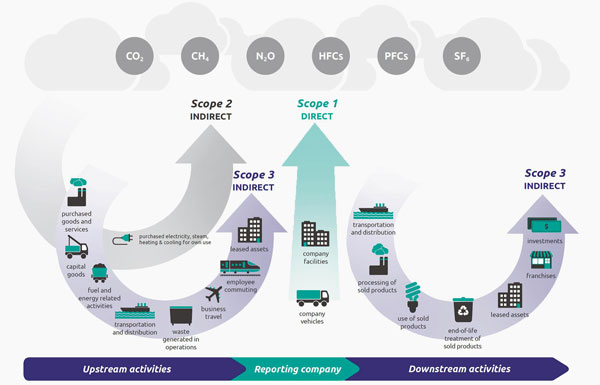

Under the GGP, emissions are labelled as one of three types: Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3.

For many companies, particularly those in construction, the categorization and defining of scope emissions has been an alien topic, resulting in GGP implications passing under the radar.

Today, however, GHG emissions and their accurate reporting have become a major issue under ESG requirements now being expected.

These three emission scopes can be challenging to track for those in the construction industry, says international sustainability consultancy Longevity Partners.

“In complex projects such as the construction of a building, the number of elements to take into account can be overwhelming.”

Scope 1 emissions are defined by the U.S. EPA as those GHG emissions that a company makes directly, for example while operating devices such as machinery and vehicles.

Scope 2 emissions are made indirectly by a company as a result of the energy generated to heat or power buildings.

Scope 1 and 2 fall more or less within an organization’s control and are understandable in principle.

However, it is the Scope 3 emissions that pose the major challenge for companies, particularly in construction. These are sometimes referred to as “value chain emissions.”

“Approximately 75 per cent of the total emissions in the lifetime of a typical building happen during the construction phase,” says Longevity Partners.

In a construction project, this includes the construction supplies, amortization of machinery, movement of company and site personnel, and other associated services. Of that 75 per cent lifetime emissions total, about 80 per cent are categorized as Scope 3.

The calculation of Scope 3 emissions is therefore critical for thorough ESG reporting. Yet, it becomes increasingly complex when attempting to calculate the emissions associated with the manufacture of materials from different parts of the world and their transportation either by boat, train or truck. Even more challenging are the emissions associated with site equipment of different ages.

Arthur Zhang, writing for 440 Megatonnes, a project of the climate policy research organization Canadian Climate Institute, says Canada is falling behind in terms of Scope 3 emissions reporting.

“There is little momentum for emissions disclosure requirements and this puts Canada’s ability to compete in the low-carbon transition at risk,” he says, despite a 2022 federal government announcement requiring mandatory reporting of Scope 3 emissions by large financial institutions starting in 2024.

Canadian regulators need to catch up, Zhang says.

To help the construction industry cope, the World Green Building Council (WorldGBC) showcased a new position paper in late 2023 during COP28 in Dubai, called Social Impact across the Built Environment.

It provides a framework outlining how the building and construction sector can address social impact across the entire building life cycle. Its purpose is to send out, “a global call for the sector to define, measure and take action on social impact to support an equitable and decarbonized built environment.”

“The industry can use this as both a guide and an action plan to truly address social impact,” says the Canada Green Building Council.

“The sector has a responsibility to reduce negative social impacts at all stages of the building and construction life cycle, to increase engagement, reporting and action around the ‘social’ criteria to unite and align efforts on the environmental elements of ESG. In other words, to action the ‘S’ in ESG.”

With better understanding, tracking and improved reporting of Scope 3 emissions, Longevity Partners says construction project partners will be better able, “to optimize their emissions by selecting responsible suppliers and contractors, and provide them with a powerful decision-making tool to identify development and investment opportunities for reducing their carbon emissions.”

John Bleasby is a Coldwater, Ont.-based freelance writer. Send comments and Climate and Construction column ideas to editor@dailycommercialnews.com.

Recent Comments