This month Vancouver’s Broadway Plan will go to city council for approval.

The draft-stage document is full of ambitious ideas for the next 30 years of building in mid-town Vancouver.

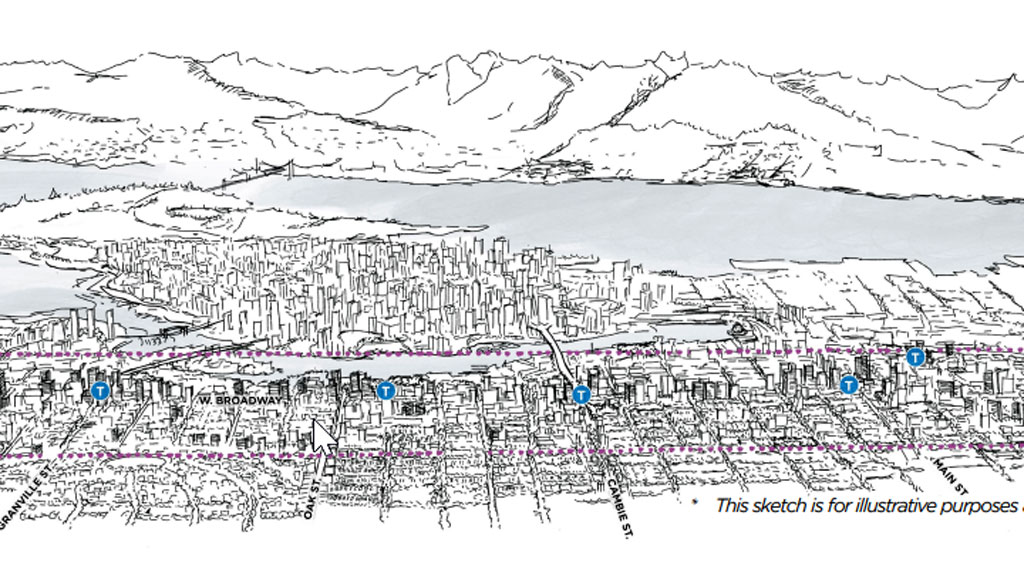

The section of the city in question lies along and around the east-west route of the under-construction Broadway subway.

The subway, a 5.7 kilometre extension of the SkyTrain Millennium Line between the existing VCC-Clark station and the intersection of Broadway and Arbutus, is scheduled for completion in 2025.

If approved, the Broadway Plan will lead to major changes in 485 city blocks between east side Clark Drive and west side Vine Street.

According to the plan, “A variety of new job space close to rapid transit strengthens Central Broadway as Vancouver’s second downtown, supporting the city’s and region’s growing economy.”

Whatever its proponents say it is, the Broadway Plan is a blueprint for the redevelopment of a large section of Vancouver that is already a going concern.

A few areas of Vancouver, such as the downtown east side, have seen better days, but mid-town is not one of them.

For the Broadway Plan to be realized, many of the existing commercial, industrial and residential buildings in the area will have to be demolished or deconstructed before new structures can rise up in their place.

“There could be many demolitions and a huge turnover of buildings,” said Christina Radvak, project manager at Light House Building Society, a Vancouver-based non-profit that promotes a circular and regenerative economy.

Radvak said the amount of demolition waste will have a huge impact on the city, and it will be challenging to deal with it all.

“And the new structures that take their place, how long will they last?” said Radvak. “The buildings need to be future-proofed, so they can continue to be used in the years to come, and not demolished and replaced with something else.”

Joanne Sawatzky, managing director, regenerative built environment at Light House, said the Broadway Plan as it stands lacks innovative ideas.

“Where are the quiet spaces or refuges, such as roof gardens, in the new buildings?” Sawatzky said. “The residents need a buffer from the noise and dirty air. Their health and well-being need to be accommodated.”

On the whole, though, she likes the plan’s goal of maintaining midtown’s scale and keeping its community focus.

“It’s done a good job of identifying the different kinds and scales of building that are needed in the Broadway corridor,” Sawatzky said.

She also likes the idea of a second downtown that’s a mix of commercial and residential.

“It will create density and vibrancy,” Sawatzky said.

Vancouver developer Michael Geller said residential livability requires density that is moderate.

“When I was studying architecture, I was taught that the floor-space ratio should not be above three (3 FSR),” said Geller. “At the time, St. James Town in Toronto, one of the densest urban neighbourhoods in Canada, had a 3 FSR.”

FSR is the ratio of a building’s floor area to the size of the property on which it is built. To calculate the FSR, a building’s floor area is divided by its site area.

“I’m worried about the ramifications of the high densities being proposed in some areas,” said Geller. “The city said they’re necessary in order to develop new housing for 40,000 to 50,000 new residents that is affordable and sustainable, but I’m not convinced.”

Patrick Condon, a professor in the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, is not a big fan of the Broadway Plan, either.

Condon calls it “a misguided economic redevelopment strategy.”

“The main beneficiaries are land speculators,” he said. “The Broadway Plan is setting up a series of unintended consequences, in which an infrastructure project leads to inflated land values and housing that is affordable to only the top 10 per cent of income earners.”

Instead, it would be better if the city spread redevelopment throughout Vancouver, reinforced by a distributed transit system.

“Vancouver was developed as a system of street car arterials throughout the city,” he said. “Some of those arterials are reasonable targets for sustainable redevelopment over time. But the Broadway subway will pull energy away from them.”

Condon said the idea of the Broadway corridor as a second downtown is impractical.

“Downtowns are important, but often their importance is overemphasized,” he said. “A distributed system is more sustainable.”

Downtown Vancouver has 18 per cent of the jobs in the Lower Mainland and its share of employment has been shrinking.

“New job growth has been taking place throughout the region, especially to the east,” said Condon. “But many people still want the primacy of downtown Vancouver to continue.”

Recent Comments