Winnipeg is unique in many good ways, but also in another way that most Winnipeggers won’t brag about: It’s the only Canadian city where pedestrians can’t cross its main intersection on the surface.

To get to the other side of the street they have to take an underground tunnel.

This unusual situation goes back to the 1970s when downtown Winnipeg was in the doldrums and the city wanted to put some life back into that part of town.

Winnipeg did a deal with a developer whereby the latter offered to build two office towers, a hotel, a five-storey bank and an underground mall at Portage and Main.

The city said “yes,” but the developer’s offer came with conditions.

One of them was that the city would close the intersection to pedestrians to bring more foot traffic to the underground mall.

As a result, since 1979 concrete barricades have blocked the intersection at street level, forcing people to either use the underground concourse, walk to another intersection or hop over the barriers and jaywalk.

Portage and Main is no ordinary intersection; it occupies a special place in a Winnipeggers’ collective psyche.

It’s where they cheered at the end of both world wars, protested during the 1919 General Strike and celebrated the return of the Winnipeg Jets.

But now the barricades and the waterproof membrane that protects the underground concourse and mall have reached the end of their useful lives.

The barricades are set to come down and the intersection will be dug up.

The city recently released a discussion paper outlining some design options and asked Winnipeggers for their feedback.

The city wants to improve accessibility, increase safety, “enhance the pedestrian experience” and attract more people to the intersection.

Some of the designs featured improved streetscaping with lights and public art and removable barriers to allow access to the intersection for special events.

Some are more dramatic.

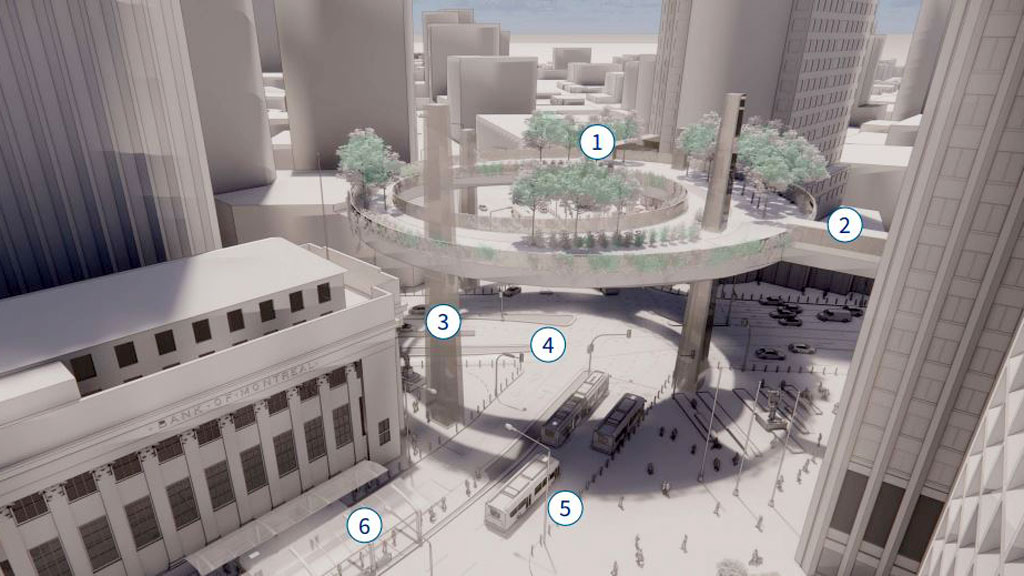

A ring of sky gardens floating six storeys in the air, with lookout towers on each corner and monumental public art that cars can drive under.

There could also be mobile food vendors, pop-up businesses, artwork or Indigenous programming.

What Winnipeggers won’t get to decide is whether they can walk across Portage and Main again.

The city says the intersection will not be opening to pedestrian crossing at street level and the barricades will be replaced.

The survey on the intersection’s future was released on April 25, Despite the consultants’ big ideas, the question on most people’s minds is whether or not to reopen Portage and Main to pedestrians.

Winnipeggers’ opinions fall into two camps.

Some believe reopening the intersection to pedestrians full-time is the only acceptable outcome.

Others are firmly in the “keep it closed” camp and are unwilling to consider anything other than keeping Portage and Main closed to surface pedestrians so that motor vehicles can zip through downtown.

Cindy Tugwell, executive director of Heritage Winnipeg, is a strong advocate for re-opening the intersection.

“We need more people on the streets downtown,” said Tugwell.

“Downtown Winnipeg needs connectivity between the various pockets of activity that exist there to bring everything together.”

University of Manitoba civil engineering professor Ahmed Shalaby says the decision on Portage and Main has unfortunately become a political football.

“There are good reasons for both opening and closing the intersection,” said Shalaby. “Equity between modes of transportation is the main reason for opening. Pedestrians should have the same right to cross the intersection as vehicles.”

On the other hand, pedestrian safety is important, as well as the need for foot traffic to sustain the underground retail stores.

“Many other options exist between a fully open or fully closed intersection,” he said. “Now that the barricades have to be removed, we should consider if they really need to be put back up. The intersection can be opened or closed without having ugly barricades. Signage should be sufficient.”

Christoper Adams, adjunct professor of political studies at the University of Manitoba, says the Portage and Main issue is a symptom of the modern culture wars between suburban drivers and urban cyclists and walkers.

“Many suburbanites don’t feel comfortable downtown, where they have to parallel-park and pay for parking,” said Adams. “They see panhandlers and erratic street people everywhere and they worry about crime. But the divisions aren’t intractable and a compromise could be reached if each side gave a little.”

Recent Comments