One of the biggest problems with futuristic domed cities is that they never get built.

In 1958, newspapers shared exciting news that the federal government was planning to build a new city centred around a concrete dome in Frobisher Bay (now Iqaluit).

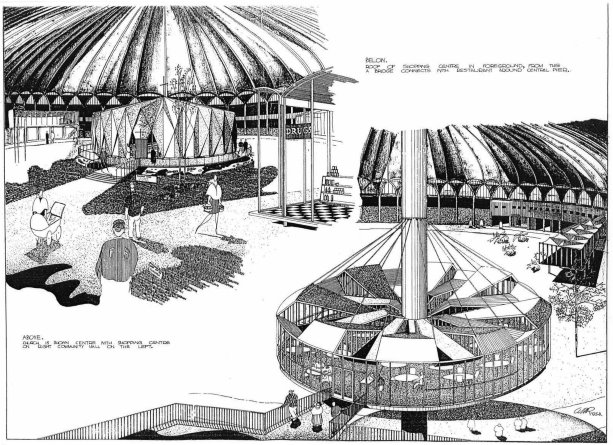

Canada’s take on postmodern northern urbanization resulted in a concept design that would have seen a 700-foot diameter built over central Iqaluit.

At the time, the population had passed 1,000, with much of the recent growth accounted for by construction of the Distant Early Warning Line, a series of radar stations designed to alert the military to possible air invasion from the north.

The federal government had planned to make the town the centre of its Eastern Arctic administration program.

Canada’s postmodern take on northern urbanization was a plan entitled: "Frobisher Bay: The Design of Accommodation for a Community of 4,500 People."

The plan is credited to E.A. Gardner, chief architect of the Department of Public Works, and William Edmund (Ted) Fancott, chief of its Preliminary Design Division.

The town’s centrepiece would be a dome 700 feet in diameter.

"… (it was) conceived in a manner similar to the gothic vaulting, but constructed in thin shell concrete with ribs radiating from a central pier, as a large fan vault," the plan stated.

"Clerestorey lighting is achieved at springing level, but large expanses of glass are not recommended owing to winter heat loss, also, there are long periods of darkness during the winter."

The dome would contain all of the necessities of modern life, including: a community centre; a swimming pool; a curling rink; a shopping centre; a hotel; a restaurant and cocktail bar; a radio and TV station; a taxi service; a laundry; two churches; a library; a post office; two schools; a fire hall; an R.C.M.P. detachment; jail cells; warehouses; workshops; a garage; and administrative offices.

An exterior hospital and clinic would be connected to the dome via underground tunnel.

Heat and power would all be supplied courtesy of an atomic reactor nestled into a cave excavated into a nearby mountainside.

While interior spaces would be heated to a comfortable 21 degrees C, the common areas of the dome would be allowed to fall to no cooler than -10 degrees C.

Although only a few kilometres of roads had been built to date, one of them would run straight through the dome:

"… it is expected that traffic will be kept to a minimum and special thought will be required to devise a ventilation system that will control the exhaust fumes," it stated.

If the initial project proved successful, noted a contemporary article in the Globe and Mail, the "system of towers and domes could eventually be repeated endlessly to create a city in the bleak Arctic."

There’s no price attached to the project, although the preliminary plan suggests ways to save money on construction:

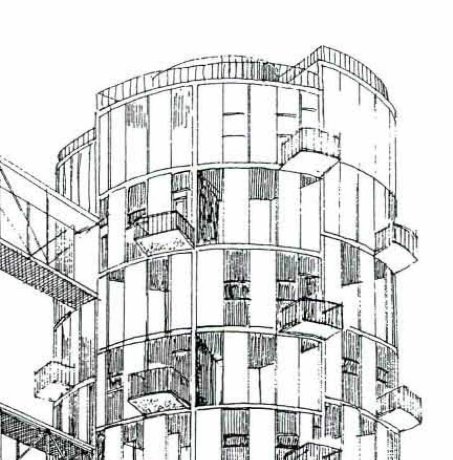

"At Frobisher, building costs are high and thought was given to economy. The system proposed is to build the apartments using sliding formwork similar to concrete silos, coupled with lift slab, proved economical methods of construction," the plan stated.

However, the most economical feature of the project is probably that it was never built.

Canadian contractors with an expertise in concrete and northern building projects were contacted for this story.

All of them declined to price out the project, in part because of an evolution of the understanding of the use of concrete in the north and in building foundations in permafrost.

Ambrose Livingstone, principal of Livingstone Architects in Iqaluit, ballparks the project at about $15 billion in today’s currency, comparing it to the known cost of building various Las Vegas hotels.

"I don’t think anyone was ever serious about building it," he said.

"I suspect those involved were just some government architects with time on their hands."

Livingstone’s firm designs a wide variety of projects, but is most often asked to work on multi-unit residential buildings.

"We rarely use concrete except for buildings that have a concrete slab foundation," he said.

"Most buildings in Nunavut use a steel pile foundation. If the project had been built, the cost to maintain it would be astronomical and it would soon fall into disrepair. Although an interesting concept, people would quickly not want to live it. I’m glad it was never built."

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed