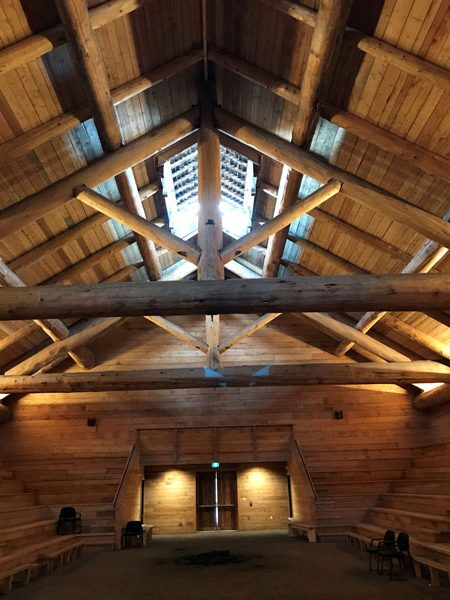

The Tsawout First Nation’s new bighouse in Central Saanich is an impressive sight from the outside, but the interior elicits an even bigger appreciation of wood construction.

Inside, four Wwestern red cedar logs, each one worth approximately $40,000, support the cultural and social hub. Originally about 90 feet long and weighing 30,000 pounds each, they represent one of the longest free span trusses in Canada, says site supervisor Ryan Kempton of Built Contracting.

Finding just the right logs became a challenge that delayed work on the Vancouver Island structure for almost five months.

Six suitable cedars were found near Woss, on North Vancouver Island, but because it was winter, they couldn’t be felled.

Working with Western Forest Products (WFP), which had logging rights in the area, the four best trees were chosen following the spring melt.

For the cash-strapped Tsawout, acquisition of the logs hinged on a generous turn of events.

“The ’Namgis First Nation heard we were in their territory looking for logs,” says Becky Wilson, the bighouse’s project manager

Because the ‘Namgis and WFP had jointly signed an agreement to manage a tree farm licence, the ‘Namgis had a say in the wood, which was on traditional territory.

“The chief heard about it and donated them to us for our bighouse,” Wilson says.

When the trees were trucked south to the Tsawout First Nation in June 2021, there were banners on the logs indicating they were to be used to build the Tsawout bighouse.

The notices were to prevent protestors, who were fighting the logging of old growth forests, from creating roadblocks or performing vandalism, says Mike McKinnon, owner of Built Contracting.

Using a 100-tonne crane, work accelerated on the project that broke ground in November 2020 and had its official opening in late October of this year.

The bighouse has several notable features. All of the wood is in nominal dimensions, Kempton says. Two mills operated at the site where logs were peeled, washed and milled.

If the lumber had been bought for the 8,500-square-foot structure, it would have been worth several million dollars, says Kempton.

The main hall, which can seat up to 900 people on cedar benches, is not heated or insulated and there is no fire suppression/sprinkler system, says plumber, pipefitter Nick Leonard of Mount Benson Mechanical.

Because the bighouse is built on reserve land, building codes and other regulations are not obligatory. Most aspects of the building follow code, but there was a deep desire to stay authentic.

Architects and engineers were used and the building, with footings that went five-feet, would withstand an earthquake.

The main hall features an earthen floor of clay and soil and there are two “smoke-outs” in the metal roof to accommodate the two open fire pits.

In addition to the main hall, there is a dining hall that seats 350 people, an industrial kitchen and an outer hallway.

Bighouses play a large role in Coast Salish identity, serving as a community gathering place and spiritual centre.

In 2009 the former Tsawout bighouse burned down, but band leaders vowed to rebuild.

“We haven’t bonded much since 2009,” says John Etzel, a Tsawout council member. “The bighouse will bring our community back together.”

Etzel spent four days raking and levelling the earth floor in the main hall for the dancers at the Oct. 19 gathering where the excitement was evident.

Without federal and provincial grants, fundraising became a significant job. One anonymous donation totalled more than $1 million for what became a $3.7 million project.

For Built Contracting, the job was rewarding and also an education in new traditions.

“The cultural aspect was very cool,” says McKinnon.

The bighouse crew was usually 15 to 20 people. One day, the First Nations workers were not onsite.

“I asked, ‘Where did they go?’ Then I was told they were out harvesting seaweed,” McKinnon says.

Another contractor was aware Tsawout was looking for assistance.

Scott Hutchinson and his son Devin operate Hutchinson Contracting. Their company had built homes on the Tsawout First Nation and a friendship with the band grew out of that work.

Putting his money where his mouth was, on National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in 2021, Hutchinson Contracting sent 10 carpenters to the bighouse site where they each worked eight hours. “We did that for free. It was the best way to show our respect,” Scott says.

Support walls and hip joists for the roof were some of the tasks the Hutchinson crew took on.

This year on national reconciliation holiday, Hutchinson Contracting sent two crews of four men each to the reserve. One crew worked on the bighouse and the other built a bus shelter.

“It makes us feel we’re acknowledging the pain they’ve had to deal with,” he says.

Your bighouse looks beautiful Congratulations ❣