The Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alta. already has an Avro Lancaster FM-159 bomber and a replica of a 12,000-lb. Tallboy earthquake bomb among its extensive Second World War historical collection. But the museum also had its sights set on a replica of the Grand Slam, the most powerful conventional bomb used during the war. It recently turned to two local woodworkers to make it happen.

The original Grand Slam was built with a hull of five-inch thick manganese steel designed to allow the bomb to fully penetrate enemy infrastructure, including submarine pens and bridges, before detonating. It weighed 22,400 lbs. and measured 26 feet long and 46 inches in diameter at its widest point.

Museum researcher Dave Birrell notes that museum’s interest in the Grand Slam was heightened by its Canadian connection. Air Commodore John Fauquier was Canada’s most decorated airman and its leading bomber pilot during World War II. He led the famous Dambusters squadron that dropped Grand Slams and other bombs on enemy infrastructure. Fauquier was the first pilot to take off and land with the massive bomb on board. Typically taking off at 110 miles per hour, the heavily loaded Lancaster couldn’t leave the ground until it reached 145, wings bending with the strain.

Andy Lockhart and John Morel are known for crafting intricate wood furnishings, with the occasional foray into Second World War-era aircraft exhibits. Lockhart bills himself as a “serious amateur” but had already restored the museum’s Lancaster navigator table. Five years ago, the pair joined forces to build the replica of the Tallboy now on display.

The team worked from what appeared to be original drawings for the bomb and compared those to measurements taken from an actual Grand Slam on display at a museum in the U.K.

“Woodworkers will tell you that half the fun is figuring out how to do stuff,” says Lockhart. “We built the front part from inch-and-a-half MDF because, unlike wood, it’s dimensionally stable. It works easily with tools, but it can be nasty stuff to cut. The dust is very permeating and there was a lot of it.”

The MDF was delivered in 4’ x 8’ sheets, which were cut into 24 sections and coopered like a barrel to form the nose. The segments were glued to circular disks made of ¾-inch plywood to maintain the model’s exterior dimensions. The next challenge was placing the nose on a lathe to round and smooth the exterior.

“We couldn’t turn it using a normal lathe set up, because the diameter was way greater than the lathe was designed for,” says Lockhart. “We also couldn’t cut it with a conventional lathe chisel, because it would have hit air half the time and then bang into the side of the segments the other half. That would overload your motor in five minutes — ask me how I know. Instead, we made up a makeshift carriage with a router on it and then got the drum spinning to complete that part of the job.”

The nose was then coated with fibreglass and painted to match the original.

The tail portion was made of sheet aluminum carefully shaped into a cone around aluminum disks and then riveted to two segments of aluminum channel. Aluminum tailfins were added later.

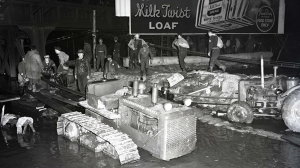

The 2,000-lb. replica took about three months to build and was removed from the woodworking shop on July 19 by crane. It was then placed on a flatbed for delivery to the museum, about an hour’s drive away.

“We definitely turned some heads on the highway,” says Lockhart. “I joke with my friends that after this project I can disconnect my security system, because the RCMP will be watching my house 24/7.”

The bomb replica is already on display at the museum. Birrell says staff will load the Grand Slam replica onto the Lancaster in 2020, as part of a commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the end of the war.

Well done on this replica, a lot of hard work went into this. Well done lads.