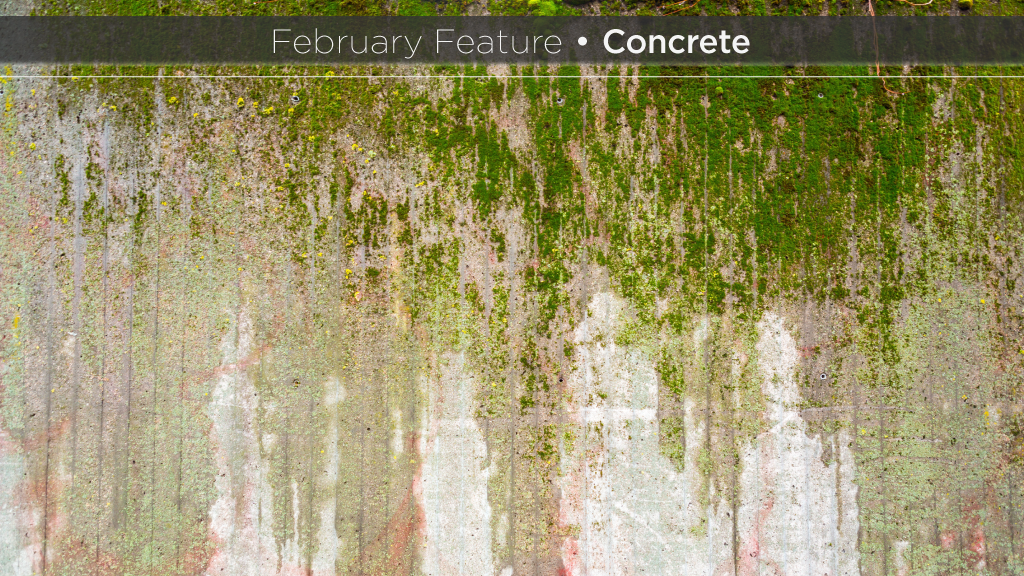

Could moss concrete be the simple green answer to many of the climate change challenges that construction design is attempting to mitigate?

Researchers at universities in Spain, London, Pakistan and the Netherlands, for more than a decade, have been looking at bio-receptive concrete, commonly known as moss concrete, to green up walls, foil graffiti, lessen heat mitigation, capture CO2 and even water management. Moss roots (rhizoids) do not invade the concrete but cling and some claim this root network also improves concrete durability.

While the concept has been gaining traction in Europe, it has had little exposure in North America.

“Moss, if it has been done correctly, can be very durable and beautiful as a biophilic installation,” said Bill Browning, managing partner of Terrapin Bright Green, an environmental strategies and consulting firm based in Washington, D.C.

But, Browning is not aware of any uses of bio-receptive concrete using moss in North America. His firm tried growing moss on crushed glass on walls, but that experiment went nowhere.

Bio-receptive concrete, according to research papers, is mainly a term for concrete that has been either mixed to encourage moss growth or has a face-design (ripples) that encourages the plant growth such as moss.

“The construction of moss concrete involves a conventional concrete layer that serves as the structural component of the building, a waterproof layer that acts as a barrier and an outer layer of moss concrete designed to allow rainwater to penetrate and boost the growth of the organisms,” according to researchers Muhammad Awais and Safeer Ullah Khattak from the Department of Civil Engineering at the Capital University of Science and Technology at Islamabad, Pakistan.

Their 2023 paper, Exploring the potential of moss concrete as an eco-friendly solution to mitigate urban heat island effect, which was presented at the fifth Conference on Sustainability in Civil Engineering, found moss can mitigate the urban heat island effect, improve building material durability, retain moisture to regulate surface temperatures and can absorb 20 times its weight in water.

Stephen Peck, president of the Green Roofs for Healthier Cities in Toronto, said moss concrete is in its preliminary stage right now and there are no installations in North America that he is aware of.

“It is emerging technology that we are keeping an eye on,” he said. “There are lots that they don’t know and there is a lot we don’t know.”

But Peck points out moss is not a panacea for water management on sites.

What is emerging today instead is a municipal holistic strategy that considers applications to buildings, sites, streets and other catchment areas such as parks that can sustain flood run-off. “They are called sponge cities,” he said.

Just as the concept of using moss concrete is evolving, so are the formulas for mixing and preparing the surface of the concrete for installation.

Researchers Max Veeger, Marc Ottele, and Alejandro Prieto for the Netherland’s University of Technology looked at the challenge of making an affordable bioreceptive concrete substrate.

They looked at four possibilities: changing the aggregate to crusted expanded clay (CEC), adding bone ash, increasing the water cement factor and using a surface retarder (prolonging set time).

Their findings, published in the Journal of Building Engineering (December 2021), determined “of these measures, changing the aggregate to CEC (p = 0.024), the addition of bone ash (p = 0.022) and the use of a surface retarder (p < 0.001) were found to significantly increase bioreceptivity.”

The researchers also found “whereas it was previously thought a pH below 10 is necessary for biological growth to take place, this does not appear to be the case.”

London’s Bartlett School of Architecture professor of innovative environments Marcos Cruz has looked at a shift to bio-integrated architecture, where hydrophilic conditions are embedded in building and material design such as panels.

The design is not geared to conventional plants but toward poikilohydric plants – algae, mosses and lichens. A series of pilots were initiated in the U.K. looking at the texture designs that could provide water capture (waves) and ridges (protection from wind).

The Netherland’s Respyre is the company that has taken the moss concrete research to the market, using recycled concrete in its manufacturing and completed projects on European multi-unit residential structures, industrial buildings as well as used moss on wind turbines bases, sound barriers and underpasses for bridges, which are prone to graffiti.

Respyre has drawn from the Delft University of Technology research but originated its own medium – a gel – for growing moss.

“At the moment we are setting up our first large-scale commercial projects,” Respyre said via e-mail. No other details were provided.

Recent Comments