Ottawa-area property available. 350 rooms. No view.

That might as well have been the description of Ottawa’s “Diefenbunker” an underground Cold War facility designed to withstand a nuclear attack, when it was put up for sale by the federal government in 1994. Initially purchased by the Township of West Carleton, it was sold for $2 in 1998 to a group of volunteers who continue to operate the facility as Canada’s Cold War Museum.

The Central Emergency Government Headquarters, also referred to as Canadian Forces Station Carp, was designed to provide for the continued operation of the Canadian government, military and civil defense operations and as many as 535 personnel should the country face atomic war.

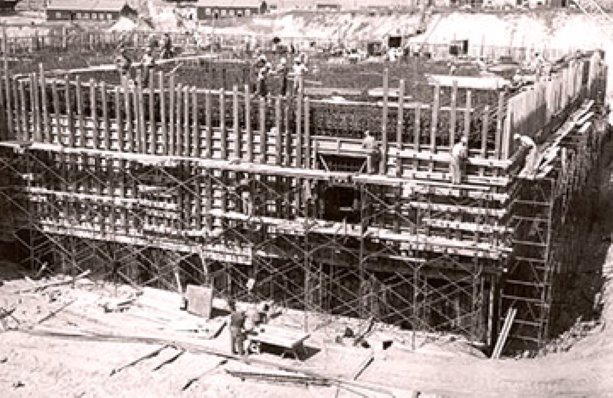

The four-storey concrete bunker measures 60 feet high and 154 feet along each wall. Construction was undertaken under the direction of Foundation of Canada Engineering Corporation Ltd., more commonly known as Fenco, on behalf of Defence Construction Canada.

“The project is not only historically significant because of its Cold War importance, but also because it was the first large-scale Canadian project built using the critical path method of construction — a forerunner of design-build,” says Doug Beaton, Diefenbunker collections manager and tour guide.

He pegs the start of construction at around October 1959, based on a series of photographs taken at the site.

“The bunker was built on a quarry on the edge of a hill,” says Beaton. “The site was picked because the water table was located 15 feet below the first pad of concrete. Gravel would also dampen vibrations caused by a missile attack.”

The cover story for the project involved construction of a military communications facility under the code name Experimental Army Signal Establishment.

“A Toronto Telegram reporter tried to investigate this big hole they were digging and was met by a nice guy with a machine gun,” says Beaton. Reporter George Brimmell subsequently published an article headlined “This is the Diefenbunker,” linking the facility with Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.

“That name was ironic,” says Beaton. “Since spouses were not supposed to enter the facility, Diefenbaker stated that, like all good Canadians, he had his own shelter that he would use in an emergency.”

Construction was completed using a team of subcontractors who built the shelter to exacting specifications.

“They used 5,000 tons of steel, including 36 I-beams and reinforcing bars estimated at 32 gauge — four inches in diameter,” says Beaton. “We’ve heard that the largest rebar made today is only 2.75 inches in diameter, so this would have had to be special order. By comparison, the Eiffel Tower is made of as little as 7,000 tons of steel.”

The concrete walls, up to four feet thick, were hand-poured using high-strength concrete as much as 50 per cent stronger than contemporary mixes. The building was further strengthened by 36 concrete columns that flared out to ceiling cones 10 feet in diameter.

Four Mirrlees diesel engines powered four generators that could produce 750,000 watts of electricity for 30 days, using 60,000 gallons of fuel stored on site. Sewage lagoons outside the building would serve as waste receptacles. Two steel blast doors, about 15 inches thick, were set into the bunker’s access tunnel.

A series of air ducts were outfitted with baffles that would seal the building in one-third of a second upon detection of a nuclear flash and subsequent transmission of neutron radiation and gamma particles. The building was completed with the addition of 15 feet of soil bulldozed onto its roof.

“As many as 200 construction workers and crane operators were employed at the site each day,” says Beaton. “The original plan was to finish the bunker in 13 months, but it actually took 24 months and was completed at the end of 1961. The ‘official’ total construction cost was $20 million, but the prime minister’s cabinet knew it was actually $33 million, which included a smaller transmitter bunker at Perth.”

With concrete in place, the building weighed 69,000 tons and was designed to withstand a blast wave of 160 psi. A five-megaton bomb would produce a force of about 100 psi at a distance of 1.1 miles and move the entire structure an estimated 1.5 inches along the gravel bed.

The facility was occupied by as many as 200 personnel each day for more than three decades, though never by the prime minister whose name it unofficially bears.

“We were told, however, by someone on one of our tours that one crummy, rainy night a guy came in with his collar turned up and his hat turned down,” says Beaton. “Construction workers said that was Dief visiting the site undercover.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed