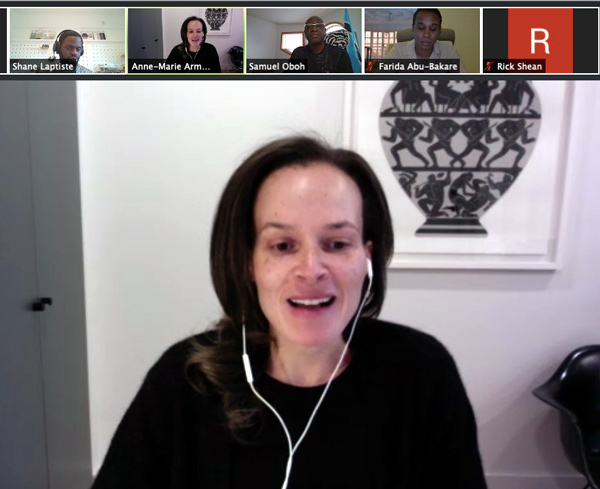

Four members of Canada’s Black architects community offered advice on partnering with other Black professionals and maintaining strong alliances with supportive white colleagues during a recent online panel billed as Lived Experiences in Architecture.

Panel moderator Sam Oboh, a former president of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, observed that Blacks make up less than two per cent of the profession in North America.

“This is an opportunity for us to…have a frank conversation around anti-Black racism in the design community,” said Oboh, who’s based in Edmonton as vice-president at Ensight+ Architecture.

“We’re in a profession that is notable for creativity, a profession that is notable for innovation. We’re good when it comes to resilience, we enhance people’s quality of life with what we do. It’s unthinkable that discrimination based on skin colour and some of the evils of the society is actually quite glaring.”

Oboh and the other three panellists are members of the Black Architects and Interior Designers Association (BAIDA). Farida Abu-Bakare is a senior project architect at Adjaye Associates and was connecting from Ghana; Yale alumnus Anne-Marie Armstrong co-founded AAmp Studio and is an assistant architecture teaching professor at the University of Toronto; and Shane Laptiste is the founder and principal of the Studio of Contemporary Architecture based in Toronto.

The panel, co-presented by RAIC and BAIDA, was held earlier this month.

Given the modest number of Black architects in practice, Oboh asked Laptiste, what can they do to develop an adequate client base?

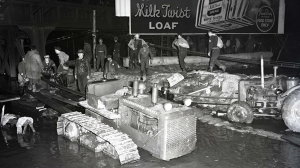

Laptiste noted that one strategy he employed not long out of McGill’s school of architecture was to reach out to community associations in Montreal. He volunteered for an organization that had provided cultural and musical education quite successfully for Blacks in the 20th century but had fallen on hard times lately and their building was in disrepair.

This was an opportunity not only for him to launch his career but also participate in the rebirth of the organization and, beyond that, community-building.

“Just being there was a good opportunity to show other members of the community what architecture can do, and how thinking about buildings in the way that architects approach buildings really can support and improve and make a building more sustainable and more realistic from a financial and an environmental standpoint,” said Laptiste.

“It’s also outreach and giving your time.”

Armstrong added that Black architects would do well to master those outreach talents as a way to increase the profession’s relevance.

“The more that we can encourage, especially with larger-scale projects, this idea of community engagement, and asking the community what their thoughts are on larger developments, housing developments, civic developments, etc., I think the more that we can engage the public in increasing the relevancy of our profession as a result,” she said.

Abu-Bakare noted that their group, BAIDA, was founded in part to create liaisons with other leaders in the Black community.

“It was really to tap into other organizations like the Black lawyers, the Black engineers, the Black financial group, the Black technology group, because those are all people who extensively become a network that we can pursue as clients, because they are all a part of large organizations that are minority-led as well,” Abu-Bakare said. “And it’s finding those people that are already leading within our community and uplifting them while we uplift ourselves.”

In her own practice Armstrong specializes in accessibility by studying borders, exploring the theme of exclusion that many Blacks experience, she said.

“We don’t really talk about that in architecture school, you know, who are our users who feel welcome in a building. Who doesn’t? How are we as designers promoting inclusion or exclusion or embedding that in our designs?” she said, noting she had students go out into the community to document thresholds of inclusion.

It was an eye-opening experience and well received by the students, said Armstrong.

She later advocated for continuing to work with white allies in the profession who can provide leadership, mentorship and opportunities that open doors. Laptiste further noted that engaging the profession — encouraging others to question their assumptions and address their biases — was imperative.

“I think it’s crucial, and it’s going to be a very long process to actually create that full equity and inclusion within the profession,” he said.

The process would create partners in reform among young, activist white architects, Laptiste suggested.

“It’s actively engaging with younger members of the profession, making sure that their voices can be heard, and not only heard but actually acted upon, if they do see injustices,” he said.

Follow the author on Twitter @DonWall_DCN.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed